Advertisement

Painting Through Parkinson's: How A Daughter Helped Her Father Find A New Artistic Vision

Resume

When up-and-coming Boston art curator Olivia Ives-Flores conceived the theme for her latest exhibition, "Menagerie," she knew almost immediately that she wanted to include some of her father's work.

She "had a feeling" that Enrique Flores-Galbis — a classic portraitist for more than 30 years — would have something vital to add to the collection. But there was a hurdle: Flores-Galbis had stopped painting portraits after he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 2015.

"I just was not up to doing these detailed things that I used to do, like putting a highlight on a child's eye, or putting just the detail that you need. [Those require] the firmness of your hand," Flores-Galbis said, sitting next to his daughter in a recent interview at newly launched exhibition space Gallery Oh at AMALGAM. The big, bright, rectangular space on Newbury Street is operated by its namesake digital branding agency, and "Menagerie" is on display there until June 11.

Flores-Galbis had been dabbling in a new style of work on a small scale in his personal studio — a much less figurative, much more colorful aesthetic that he hadn't revealed publicly.

Ives-Flores couldn't let go of the idea that her father had to be in "Menagerie," which revolves around themes of flora, fauna and wildness. "Whenever I curate an exhibition, it really starts with the feeling," she said.

To sit with Ives-Flores and Flores-Galbis is to witness a palpable, complete trust. They can often communicate a feeling or an idea with simple glances and no words.

Their connection was cultivated in a creative household helmed by artists in New York City. Ives-Flores's mother, Laurel Ives, is a graphic artist who consistently held the 9-to-5, while her father painted at night and spent the day with Ives-Flores and her sister Mia.

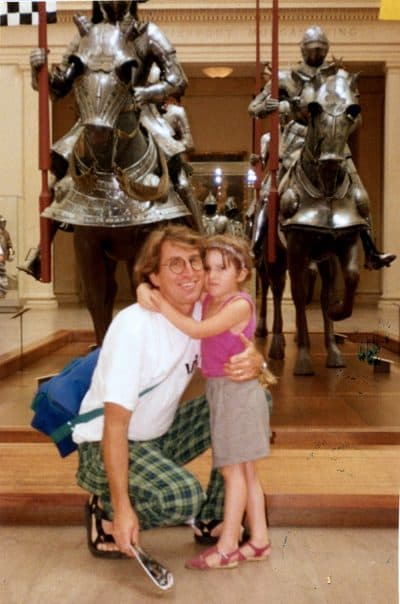

"We were always making art around the table. I grew up in the museums and tagging along with him," Ives-Flores said of her father. "He always reminds me that he talked to me as an adult even when I was a baby, and would tell me about art and illuminate these great masterpieces even when I was still in a diaper." (Ives-Flores took her first steps at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Once, Flores-Gablis took his daughter to a pool when she was almost 2 years old. He'd read that children have an innate ability to hold their breath underwater.

"I would throw Olivia in the water in the deep end, and then I'd jump in with her and then we'd be underwater and I would watch her as she held her breath," Flores-Galbis said. "I could see that she trusted me. There was not one iota of fear in her."

That bond is still there. When Ives-Flores called her dad and asked him to paint new works and reveal them publicly for the first time in her exhibition, it was his turn to take the plunge with her. When he returned to the studio, ready to paint through Parkinson's, he had to fully develop the new aesthetic he'd been exploring and discover a sensibility for his work.

"With Parkinson's, there's a lack of dopamine in your brain. Dopamine is sort of the key chemical in you enjoying the world, in making you happy and giving you a reward," Flores-Galbis said. "And I wanted to just increase the reasons for reward."

Gone were the days of the beautiful but muted portraits. This time, Flores-Galbis sought something else when he painted. He wanted to activate happiness in his brain through vivid color and intricate shapes.

"When I'm out of the studio, I'm feeling so-so," he said. "When I'm in the studio, I'm flying high and I'm the best that I am all day, and that's the gift that art has. I hope that that feeling translates in the work."

His new work is a meditation of inner seeking. In a painting called "A Tropical Childhood," deep, rich oils in blue, vibrant greens, yellows and oranges form an abstract shape. There are remnants of a raft in an ocean, tropical tree leaves, a menacing tiger, the silhouette of a child and boots and limbs peeking out — alluding to Flores-Galbis' early days in his home country of Cuba.

He left the country at the age of 9 for a children's camp in Miami as part of Operación Pedro Pan, during which Cuban families sent some 14,000 unaccompanied children to the United States between 1960 and 1962, after Fidel Castro rose to power.

Also among the collection at "Menagerie" are luminous, abstract paintings with equestrian themes. Ives-Flores interprets the horses in her father's new style of work as symbols of his rebirth as an artist.

"Having something that is bigger than you are — it really could take you for a ride, but you saddle up and you tell it where to go," she said. "I think that there is such a bravery in that."

It was Flores-Galbis' family who inspired him to evolve as an artist, even after losing some of his motor-functions. "Even though my fingers seemed to have lost a great deal of dexterity and muscle memory, I never stopped painting. Olivia, Laurel and Mia would not let me stop. Olivia called me every day, she still does. She dreamed up opportunities to show my work, to keep me engaged, to keep pushing as always."

Before "Menagerie" opened, Flores-Galbis came to Boston from New York to help his daughter hang the artwork at the gallery. The activity turned out to be a silent, delicate dance between father and daughter — like their whole lives had led to this moment.

"We did it without talking most of the time, and we were just in perfect syncopation and knew organically where each piece needed to live," Ives-Flores said. "It was like this kind of wordless interaction."

And that connection, built on creativity and trust, enabled Flores-Galbis to find a new artistic vision and a new purpose in his brush strokes.

This segment aired on May 14, 2018.