Advertisement

From Seminar To Online Journal, 'Freedom School' Celebrates Contemporary Black Creators

The seminar met for two glorious, unforgettable semesters. Classmates discussed contemporary Black thinkers and cultural producers, from painter Toyin Ojih Odutola, to feminist writer adrienne maree brown, to hip-hop artist and producer Flying Lotus. They studied the work of Black activists and social movement leaders. They consumed books and podcasts on Afrofuturism, emergent strategies, identity politics and the abolition of prisons. They shared meals and built community. There was no professor present, which meant that students of color could share ideas freely without the influence of the white gaze or a traditional hegemonic classroom structure. Required course materials were provided; every single book was free. It was everything Black students have been denied despite the privilege of attending the most respected and well-resourced educational institution in the world.

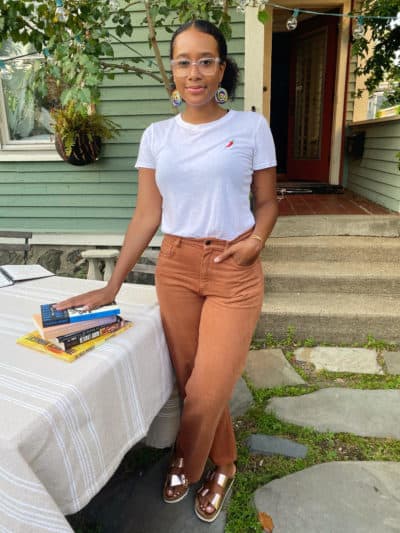

“I don’t think that’s an accident that a place like Harvard isn’t able to offer Black students who want to study Black radical thought this space to engage critically in a way that also pushes against the hegemony that’s so deeply entrenched in Harvard, and the hegemony that Harvard reproduces,” says Najha Zigbi-Johnson, a scholar of Black American movement building who recently graduated with her master’s in theological studies, and was responsible for devising, pitching, funding and populating the seminar. “I think there's fear around what does it mean when Black folks really talk about what's on our heart? And when Black folks really talk about shifting power? That's not something that places like Harvard are interested in really engaging in.”

The course was called “Freedom School: A Seminar on Theory and Praxis for Black Studies in the United States.” With it, Zigbi-Johnson carried on a rich legacy of radical Black imagination and social justice work that has its roots in the civil rights movement.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and NAACP joined forces to create the first “freedom schools” in an effort to get as many Black Mississippians registered to vote and to prepare them to pass the state’s notoriously difficult voter registration exam. Designed by progressive educators from across the United States, the curriculum in these schools was revolutionary, helping students learn Black history that had previously been hidden from them, and explore their political and creative passions.

On the first day of fall semester, Zigbi-Johnson set up eight chairs in a small classroom, hoping a few curious students might pop by. But she soon found out she’d need a bigger room. Seventeen graduate students from across the university’s 11 schools showed up for class, eager to engage with something new. Something experimental — and completely community-run. To realize a collective vision that was decidedly anti-capitalist, anti-white supremacist, and centered queer Black perspectives.

Zigbi-Johnson didn’t plan to create her own freedom school when she came to Harvard. Frustrated by the lack of Black representation among faculty members and with the limited, myopic syllabi that hadn’t progressed in studying Black thought past the late 20th century, she saw an opportunity for students to seek it out for themselves. With the help of Kimberley Patton, a long-tenured white professor, Zigbi-Johnson was able to secure the support she needed for the autonomous work of the freedom school.

“What I like to understand this freedom school to be is an experiment in freedom. Because we don’t have a lot of freedom. In school, we’re taught by someone. We’re told what to read. But I was like, ‘Well, what if we create a syllabus together? And what if we decide what’s important to us? And what if we make the books free, and open the space to anyone who chooses to come?’” Zigbi-Johnson explains. “Like, thank God for W.E.B. DuBois and for our people who were writing at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. But we’re in different places now.”

Born and raised in Harlem, Zigbi-Johnson attended a small Quaker college in North Carolina before moving to Cambridge. It was in the South, she says, that she became politicized — getting involved in statewide organizing efforts with the Movement for Black Lives and Ignite NC — and learned about the work of the original freedom schools.

But at Harvard, she and her peers found themselves struggling to hold simultaneous truths.

“It’s a complicated relationship because we do have so much privilege in terms of our social capital and in terms of the resources we do have access to, even though there are roadblocks to accessing a lot of it,” says Lesedi Graveline, 25, of Somerville, a fellow master’s candidate and participant in Zigbi-Johnson’s freedom school.

“I feel a great deal of responsibility as a young Black scholar to redistribute those resources and to find ways to uplift the voices of people like Stacey Borden.”

Borden is a local movement leader and the founder of New Beginnings Reentry Services, an organization that provides support and guidance to women who were formerly incarcerated. She and many other community members outside of Harvard — what Graveline calls the seminar participants’ “constellation” of networks across the country — contributed poems, letters, paintings and digital artwork to “Freedom School,” a publication that Graveline and Zigbi-Johnson co-edited and curated. In the spirit of the seminar, the literary journal will be made completely free for anyone who wants to access it, published July 17 on a website that Zigbi-Johnson and Graveline designed.

The seminar had originally intended to culminate with a grand convening, a direct subversion of the “normative form of conferences that places like Harvard have all the time,” says Zigbi-Johnson.

But when the coronavirus pandemic made sharing physical space no longer possible, Graveline saw an opportunity to make something tangible instead. She enlisted the help of graphic designers Chindo Nkenke-Smith and Giovanna Araujo, contacted a printing press and began coordinating the publication’s creation.

Graveline and Zigbi-Johnson spent up to eight hours a day together on Zoom for more than four weeks, tending to submissions and dreaming up ideas. They wanted to offer Black people an oasis of peace amidst recent civil uprisings and the public spotlight on state-sanctioned violence, which has been both motivating and overwhelming for the small team.

“It's important for us to be able to produce something that I can bring back to my parents and my grandparents and my siblings. And that doesn't mean that it's not intellectual. It doesn't mean that it's not multilayered,” Graveline states. “But inherently it has to deviate from the jargon that places like Harvard forced us to learn.”

Lovingly created by and for Black people, “Freedom School” invited its contributors to freely create their visions of the future, and respond to the current cultural moment, through the playful lens of surrealism. Zigbi-Johnson insisted that no submission be turned away. Each one was uplifted and treated with care in order to actualize the abolitionist values of the freedom school.

“Hopefully, it's a space where people can continue to process emotion,” Zigbi-Johnson adds. “Blackness continuously grows and reshapes itself in real-time, as a reflection of the sociopolitical moment Black folks exist within. And so you see young Black people creating art, theorizing, responding to this moment. And that's culture in action.”

While the pandemic makes the future difficult to predict, Zigbi-Johnson plans to bring her freedom school curriculum back home to Harlem, where she hopes the seminar and publication can serve as a template for other communities. The message of freedom school, she says, is that it’s malleable and ever-evolving; it reminds Black communities of their own power to manifest what is important to them.

Zigbi-Johnson and Graveline also intend to continue to collaborate, with focus on producing a second volume of the “Freedom School” publication. Meanwhile, Graveline states that the freedom school cohort at Harvard has formed a community that extends far beyond the classroom or any physical location.

“[Whenever I left class] I felt very energized,” Graveline says of her time in the course. “I felt like, we can do this. We can do this work. It's possible. And there are people who are doing it.”