Advertisement

The Literary Legacy Of Pauline Hopkins

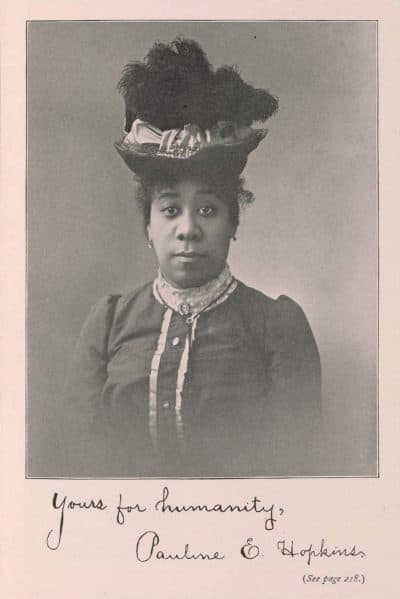

Pauline Hopkins was a multitalented author, journalist and editor who pioneered horror, science fiction and fantasy writing at the turn of the 20th century. She wrote among the first (if not the first) theatrical drama and detective stories authored by a Black person, yet, her fiction does not have the same recognition as household names like Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” or Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” nor does her nonfiction have the same acclaim as W.E.B. Du Bois’.

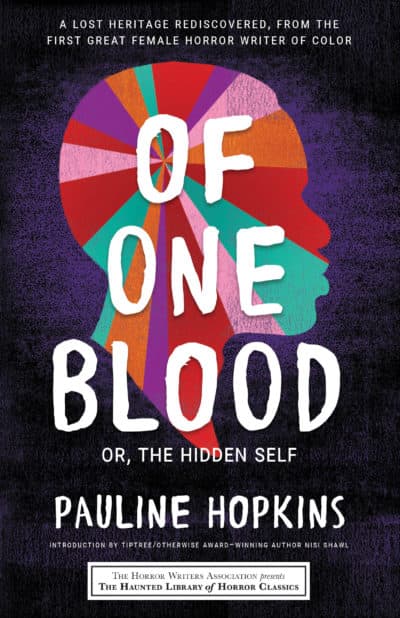

This is partly due to the unfortunate reality that archival materials related to marginalized figures, especially Black women like Hopkins, are difficult to exhume when they are no longer active. The other part is the long-standing racist and sexist ideas behind what constitutes “literary canon.” To elevate awareness of Hopkins in the 21st century, two of her four novels have recently been reissued: “Of One Blood: Or, the Hidden Self” was reissued on Feb. 9 and “Hagar's Daughter: A Story of Southern Caste Prejudice” in December 2020.

Entering the Spotlight

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins was born in Portland, Maine in 1859 and matriculated through Boston public schools. She went on to become known as “Boston’s favorite colored Soprano” in the late 1870s and early 1880s for her singing as a soloist and as part of the Hopkins Colored Troubadours, according to a 1882 advertisement from the Boston Globe. By 1879, she had written the play “Peculiar Sam; or, The Underground Railroad, A Musical Drama in 4 Acts” (also known as “Slaves’ Escape and A Flight for Freedom”), which many of Hopkins’ contemporaries considered to be the “first colored drama.” Hopkins’ play “provided American audiences with the first staged reenactments of slavery that were not offered through the lens of the white imagination,” according to historian and Wesleyan professor Lois Brown in the introduction of the 2020 edition of “Hagar’s Daughter.” This would be the first in a line of Hopkins’ works where she talked openly about race through a medium that was entertaining to wider audiences.

Hopkins’ public spotlight only grew from there. From the 1880s onward, Hopkins gave lectures and other readings to both Black and white audiences as part of church programs and concerts. Her subjects ranged from prominent Black figures from history, the Haitian Revolution, denouncing white-on-Black violence, lynching, and presidential candidates.

Hopkins wasn’t shy about her politics in her writing, either. Unlike the conservative Booker T. Washington, she favored agitation methods to address racial inequality, spoke against imperialism and centered Black women at the heart of the issues. Dr. Cherene Sherrard-Johnson, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin and president of The Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins Society, says, “Hopkins was very forthright in her activism against lynching and sexual violence against Black women. These subjects were not talked about, especially sexual abuse, and Hopkins talked about them as openly as she could in her novels.”

During some of her speeches against the convict lease system and lynching, she would read sections from her debut novel “Contending Forces” (published in 1900) to illustrate how these cruel practices targeted Black Americans. Science fiction and fantasy author Nisi Shawl (who wrote the introduction to the 2021 edition of “Of One Blood”) says, “I think what I admire the most about her is her fearlessness…the audacity of saying ‘This is what happened,’ although you’re not supposed to talk about it, yet here it is.”

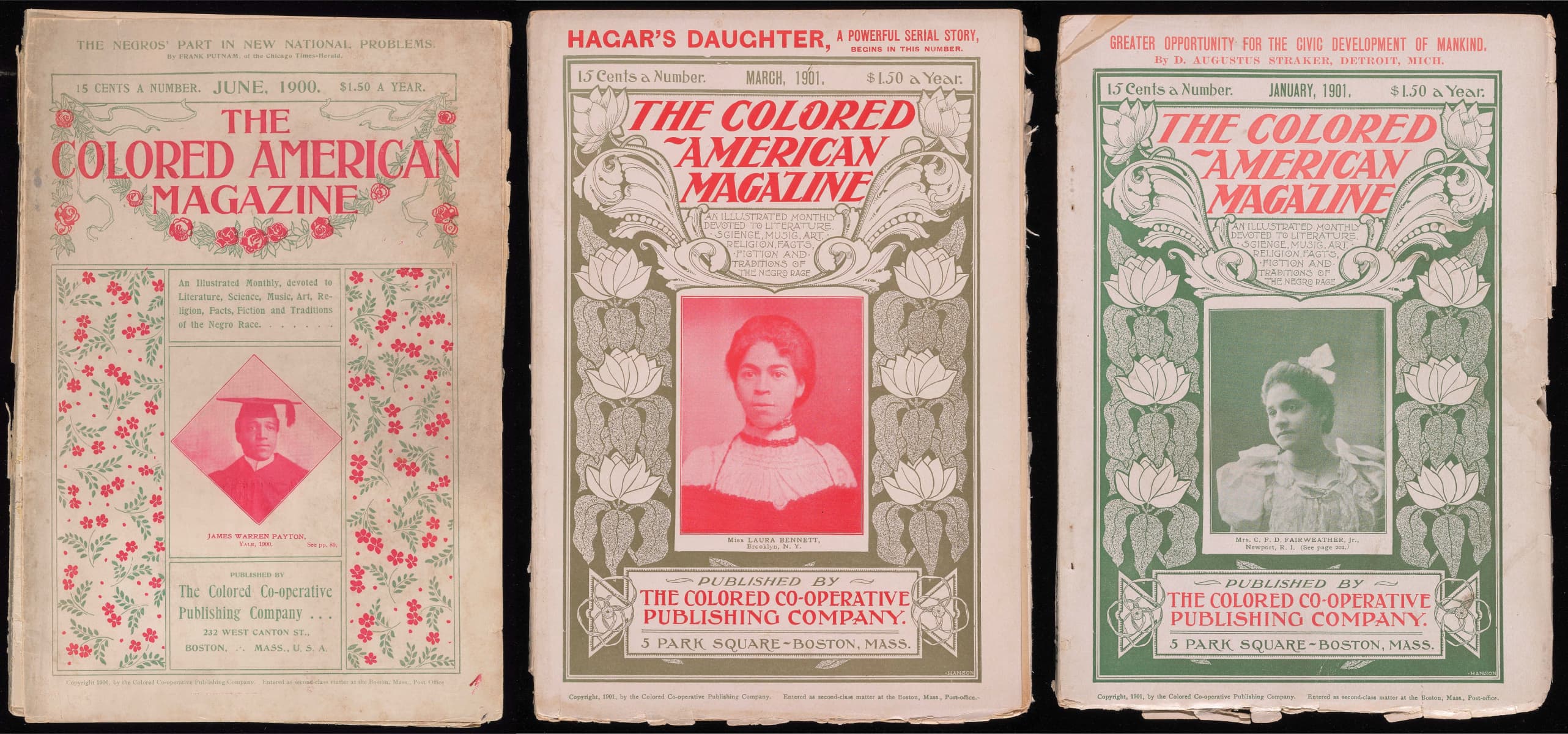

The Colored American Magazine

Another platform for Hopkins’ arguments was the Colored American Magazine, the literary journal she edited. The Colored American Magazine was the widest-circulating African American literary publication before W.E.B. Du Bois founded The Crisis in 1910, the official publication of the NAACP. As editor, Hopkins made sure the Colored American Magazine highlighted the political conversations that arose among Black intellectuals, usually favoring radical stances in line with Du Bois rather than Washington’s compromises . In both the nonfiction and fiction she wrote for the magazine, Hopkins advocated for an activist movement as steadfast as the abolitionist movement to elevate the status of Black Americans, since their relationship with white Americans remained dire in the post-Reconstruction era.

Sherrard-Johnson notes that Hopkins “wanted to share race in a way that was authentic and humanizing, but she also wanted to entertain.” Between 1901 and 1903, Hopkins serialized her three novels after “Contending Forces” in the Colored American Magazine. “Hagar’s Daughter” is one of the first detective stories written by a Black author, but it also explores mixed race identity and the dangers that Black women face. “Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest” is a harrowing tale of two people who are abducted into slavery and then escape, but it also allows the heroine to do some of the rescuing before getting a happily-ever-after romance. “Of One Blood” is part ghost story, part adventurous plot to a long-lost African kingdom, and it once again explores the idea of Black characters who can pass as white. By writing thrilling cliffhangers, Hopkins enticed readers to buy the next issue and successfully ensured reinvestment in the Colored American Magazine.

Hopkins’ use of romantic and adventurous plots to explore philosophical questions about race and society was an innovative approach not employed by her peers. Shawl notes that Hopkins blended Afrocentric traditions (such as the art of the coincidence, fate and the unseen) with Eurocentric storytelling forms of “society” novels (aka “drawing room dramas”), “lost world adventures” and the more modern idea of a “problem” novel. “One of the strengths of Afro-Diasporic culture is that we have to make do with what we’ve got,” Shawl says. “We’re not going to conform to anyone’s rules on how to use what we’ve got, we’re just going to use it.”

Sherrard-Johnson has taught “Of One Blood” alongside Henry James’ “The Turn of The Screw” because of their similar gothic feel and psychological elements. “The occult and mesmerism were prevalent in popular culture, they were seen as a form of science at the time,” says Sherrard-Johnson. She points out that the motif of a formerly enslaved ghost in “Of One Blood” would later famously appear in “Beloved” by Toni Morrison.

As Shawl notes in the introduction to “Of One Blood,” and as other scholars have pointed out, the lost civilization in “Of One Blood” is a “proto-Wakanda” a la “Black Panther.” They are two hidden kingdoms in Africa who are proud of their ancestry and have “all the arts and cunning inventions that make your modern glory,” according to the book. Tensions rise when newcomers (who have secretly shared this ancestry all along) ask why the advanced civilization has kept themselves and their prosperity a secret, when they could “raise standards of Black people of diasporic level,” as Sherrard-Johnson will say in a forthcoming paper.

Hopkins’ implicit and explicit criticism of Washington led to a fraught relationship between the two of them. She first declined to work with Washington when he invited her to come to Alabama as a stenographer in 1894. In 1904, Washington sent an associate to purchase the Colored American Magazine, relocate operations to New York and eventually oust Hopkins as editor. “The men she worked with, particularly Booker T. Washington, respected and understood her, but my thought is that they felt threatened by her,” Sherrard-Johnson says.

A Literary Legacy

After Colored American Magazine, Hopkins wrote for several more prominent magazines and published one last novella, but little is known about her work after 1916. Sherrard-Johnson posits, “Colored American [Magazine] provided an audience and a motivation for her work. When one is discouraged, it’s hard to keep writing.” Hopkins continued to support herself through steady stenography work for the City of Cambridge, the Massachusetts State House and a college in Cambridge which the introduction of the 2020 edition of “Hagar’s Daughter” says many presume to be MIT. Her life ended tragically from burns sustained after an oil stove explosion in August of 1930.

Although Hopkins legacy was in danger of being lost to time due to her status as a Black woman who “was not following safe conventions of storytelling as far as the literary establishment goes,” as Shawl says, American society has finally started to recognize the vital perspectives of marginalized figures. Sherrard-Johnson adds, “For a long time, we had an established idea of major American writers — they were white and male, with some notable exceptions in New England, some Dickenson, some Alcott, and Harriet Jacobs’ ‘Life of a Slave Girl.’” But now that archival literature is being studied with a wider scope, these works are becoming more accessible to the general public. As Shawl says, “It’s gratifying to those of us who are on the margins racially, how this maybe influenced others in my community, saying, ‘Hey, we were always there!’”