Advertisement

How Raytheon Aims To Detect And Fight Nuclear Weapon Threats On The Horizon

Resume

Part 2 of 2. Here's Part 1.

In the main lobby of Raytheon's massive Andover facility is an ancient but familiar-looking kitchen appliance.

"Decades ago there was a Raytheon engineer named Percy Spencer who was experimenting in his lab, and a chocolate bar in his pocket melted," recalls Thomas Laliberty, vice president of Raytheon Integrated Defense Systems.

That gooey eureka moment gave birth to Raytheon's best known commercial product: the Radarange. The engineer discovered the microwaves generated by the radar component he was working on could heat food.

"Essentially the electronics that make up radar are the same basic electronics that are in microwave cooking," Laliberty says.

Radar works by bouncing microwaves off of objects to determine speed, distance and direction. The top secret development of the technology helped the Allies win World War II.

Today, radar is Raytheon's bread and butter, a critical part of virtually every missile system it builds.

"Business is good," Laliberty says. "As you might imagine, the threat drives our business, and the threat continues to grow around the world."

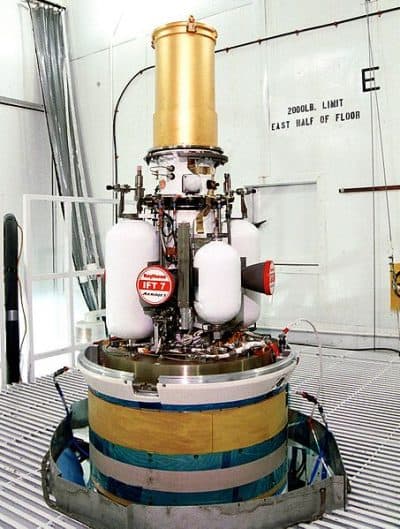

Raytheon plays a key role in something called Ground-Based Midcourse Defense. GMD uses a global network of land- and sea-based radars designed to detect the launch of enemy nuclear-armed ballistic missiles, to determine trajectories and targets, and then fire defensive missiles based in California and Alaska.

The idea is to slam into an enemy warhead as it travels in space, and smash it to smithereens with a kill vehicle. Basically, using a bullet to hit a bullet out of the sky. At least that's the way the $40 billion system is supposed to work.

President Trump likes the GMD. "We have missiles that can knock out a missile in the air 97 percent of the time, and if you send two of them, it's going to get knocked out."

Physicist Laura Grego disputes Trump's numbers. "We certainly have a strategic missile defense system that doesn't work very well," she says.

Grego, who's with the Cambridge-based Union of Concern Scientists, investigated the nearly 20-year-old GMD program.

"So out of the 18 tests of this system trying to hit an actual target, it hasn't succeeded 50 percent of the time, just shy of that, and out of the last five tests it's only succeeded twice," she says.

"That's why you do testing," Laliberty responds, "to essentially find the issues that have to be resolved."

Laliberty doesn't dispute Grego's statistics but does come to a different conclusion.

"I think we can look at the recent test results for [GMD] and have a lot of confidence from those," he says. "Those were pretty stressing tests that the system actually performed very well."

The GMD is supposed to hit enemy warheads in space, but the refrigerator-size kill vehicle's track record has been poor, and Raytheon is redesigning it from the ground up.

But now there is a newer technology that could dramatically transform the threat of nuclear-armed missiles. It's already disrupting Raytheon's business.

A New Tech — And A New Threat

A Chinese video shows off Beijing's new hypersonic glide vehicle. Launched atop a long-range ballistic missile, carrying nuclear warheads, the reentry vehicle can maneuver through the atmosphere as fast as 20 times the speed of sound, able to evade existing ground- and sea-based radar systems.

If you can't see it, you can't shoot it.

"Hypersonic glide vehicles are threats that both Russian and China are building now that are very significant in being able to see them and provide warning," says Air Force General John Hyten, head of the U.S. Strategic Command. "We need to figure out how to deal with those."

India, Israel and the U.S. are also aggressively developing hypersonic vehicles.

In recent years Raytheon has reportedly invested half a billion dollars in hypersonic technologies. Company details are highly classified.

And there are places in Raytheon's Andover plant the Department of Defense keeps off limits. So we move on, down a factory corridor, where teams of Raytheon workers make the next generation of military microchips. They're the brains for new radar systems and missile sensors able to endure the harsh conditions of space, part of an early state defense project to spot enemy hypersonic vehicles from above, using satellites and high-flying drones.

"So our adversaries have been watching that again, "Hyten says, "and that's why they're going down hypersonics and maneuvering reentry vehicles. Those are counters to us, so we have to counter them."

The Pentagon is also testing unconventional weapons that could zap hypersonics out of the sky using intense blasts of microwaves, the technology Raytheon helped pioneer, and light.

"I think in the future you'll see a wider range of things like lasers and other types of directed energy-type technologies that will be brought to bear," says Raytheon's Laliberty.

But Grego, of the Union of Concerned Scientists, warns against an escalating arms race. She says any future missile defense system will only instill a false sense of security.

"So the idea is if you have a 6-foot fence protecting you, they might build a 7-foot ladder," she says, "so as you build more missile defenses your adversary will build more missiles."

Federal funding for hypersonic technologies has been only a fraction of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency's budget. But there are calls to fast track spending.

And as the race to place sensors and energy weapons into space takes off, the sky may no longer be the limit for anti-missile systems -- and for the fortunes of Raytheon.

This segment aired on April 25, 2018.