Advertisement

COMMENTARY

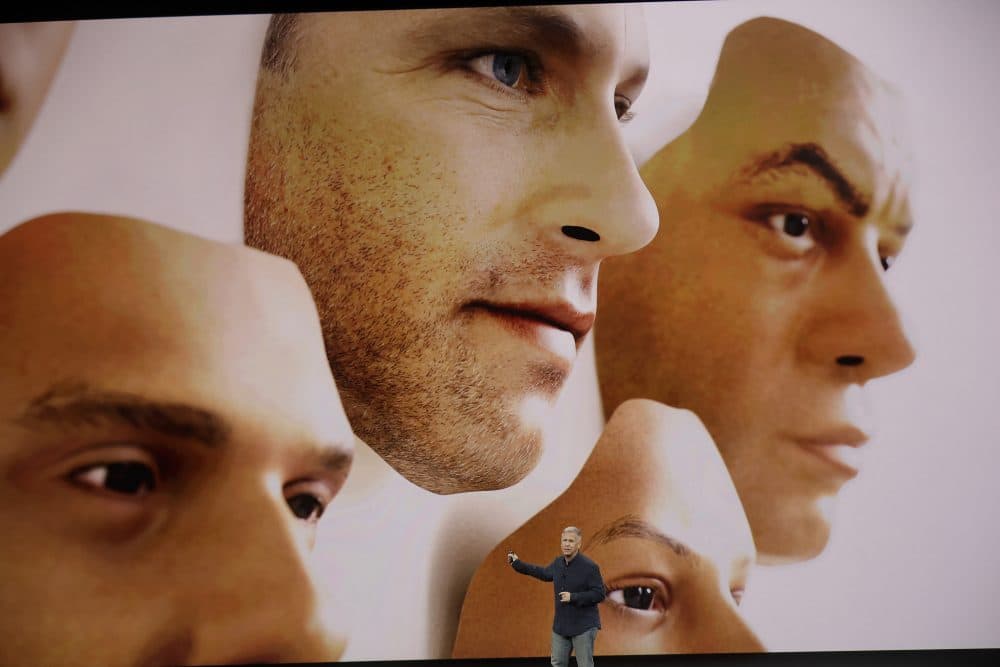

Beware Of Apple's New Face ID

You may soon be able to unlock your iPhone by pointing its cameras at your face. For legal, cultural and even practical reasons, I suggest you don’t.

Last week, we learned that the next generation iPhone, the iPhone X, will ship with a new form of biometric identification. Currently, some iPhone users have the option of using their fingerprint instead of a passcode. Apple’s Touch ID biometric technology makes this possible. On the iPhone X, Touch ID is gone, along with the home button that facilitated it; in its place, we find Face ID and a big old mess.

What’s the problem with face recognition on the iPhone?

For starters, using your face as the key to open your phone may make it easier for the government to rifle through your most private information. In 2014, the Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement must get warrants to search our cellphones, even if we are arrested. But we know that some police officers, like everyone else, don’t always follow the rules. If you use a passcode to protect your iPhone, and you refuse to give up your passcode, the cops are out of luck, even if they seize it without a warrant. But if your face is your passcode, all law enforcement has to do to get inside your device is hold your face still and point the phone at it — something they could theoretically do even if you are unconscious.

And even when it comes to judicially authorized searches, a passcode is likely a better choice. While the law hasn’t fully developed in this area, we have reason to believe a passcode is a better option than biometrics even in cases where law enforcement does have a warrant to search your device.

In certain contexts, the federal government has decided it doesn’t even need a warrant to search your phone. The Department of Homeland Security, for example, claims that we have limited (to non-existent) Fourth Amendment rights at the border. As a result, DHS agents have conducted thousands of device searches at airports and land borders, even when they have no warrants or even reasonable suspicion to believe that the target of the search has broken the law. Border agents cannot legally force you to give them your passcode, but if they can get their hands on your device, they can point it at your face to unlock it. (This week the ACLU of Massachusetts filed suit challenging warrantless border device searches.)

Besides the legal stuff, there are extremely serious cultural and philosophical problems with face recognition technology. If popular tech companies (and airlines like JetBlue) normalize facial recognition by needlessly injecting it into consumer products used by millions of people, we as a culture will grow more and more accustomed to face recognition in the modern world. And as the film, “Minority Report,” shows us, that’s a significant problem. Face recognition technology in the hands of major corporations and governments means the end of anonymity in physical space. It means pervasive, unending tracking that can shift seamlessly from your smartphone’s camera to the cameras on digital advertising message boards at the MBTA to the city’s networked surveillance camera system and beyond. That’s simply too much power for corporations and governments, and enables too dystopian forms of social and political control. It’s hard to imagine a flourishing democracy in a techno-surveillance state without limits.

Some people say the expansion of face recognition is inevitable, but that’s nonsense; nothing is inevitable besides death and taxes. We the people, both as consumers and residents of a democratic society, have the power to shape our future — and technology is a central part of that future.

So flex your muscles where you can. Turning off the Face ID feature on your new iPhone may seem like a small act of resistance, but companies pay close attention to how their innovations are received. If millions of people say, “no thanks” to companies like Apple and JetBlue that try to normalize facial recognition, it’ll send a strong message about what we are comfortable with, and what we aren’t. And if companies back away from face recognition, sensing discomfort among consumers, it’ll be all the more difficult for governments to convince elected officials and the rest of us of the need for persistent tracking systems that obliterate privacy in public as we’ve long known it.

Finally, there is one practical reason to avoid using Face ID: It is probably clunky and inefficient. Think about it: No more unlocking your phone under the table at meetings; now you have to lift it up, hold it out in front of your face, and stare right at it. We unlock our phones dozens of times a day, and this newfangled means of doing so seems out of sync with how most people use smartphones.

For all of these reasons, please join me in saying to Apple: Thanks but no thanks. I’ll pass on the Face ID.