Advertisement

Commentary

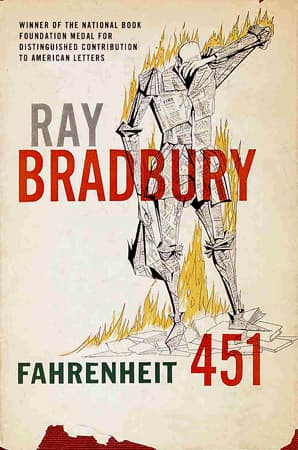

HBO Has A New Take On Ray Bradbury's Dystopian Masterpiece. Here's Why 'Fahrenheit 451' Still Matters

The wonder of a great science fiction writer is that they often predict the future with an eerie precision. In 1953, when Ray Bradbury wrote "Fahrenheit 451," fewer than half of all American homes had a television. Bradbury envisioned a future in which our citizens spent their lives in the thrall of vast flat-screen TVs called “parlor walls” and wore tranquilizing earbuds call Seashells. How’s that for eerie precision?

No wonder HBO is offering up a new adaptation of this old classic. And yet Bradbury’s most famous work remains his most widely misunderstood.

Our hero is a fireman named Montag whose job is to burn books. Because of this twist, the novel is widely regarded as a parable about the dangers of censorship.

Not so. The reason books have been outlawed in Bradbury’s dystopia is because “the public itself stopped reading of its own accord.” His central concern isn’t the tyranny of the State, but the self-induced triviality of the people.

In fact, the characters in “Fahrenheit 451” don’t live in terror of Orwellian Stormtroopers. What they’re afraid of is the painful truths of an examined life.

Montag discovers this for himself when he returns home to find his wife Mildred and her friends sitting before the parlor walls. He unplugs the walls and tries to engage them by talking about an upcoming war, the death of friends, family, politics. The women are indifferent to anything beyond the pleasures of the moment.

... Americans are becoming a people incapable of facing the essential moral crises of our age.

“We need not to be let alone. We need to be really bothered once in a while,” Montag cries, in exasperation. “How long is it since you were really bothered by something important, something real?”

This question is the reason “Fahrenheit 451” resonates so deeply with our historical moment: Americans are becoming a people incapable of facing the essential moral crises of our age.

Amid all the telegenic pundits and roaring demagogues, almost nobody is talking about how to address climate change, income inequality, health care for the poor, the rights and dignity of our most vulnerable citizens. More precisely, nobody is listening to those who want to confront these problems.

Instead, we’re busy hate-watching democracy, rubbernecking the manifest corruption of the millionaires who run our government, and wasting our energies on partisan trolling, when we should be pursuing a common good by solving our common problems.

The true villains in Bradbury’s world aren’t sadists, they’re sheep — citizens incapable of deep thought or feeling. Like us, they live in relative abundance. Like us, they have plenty of time for thinking. And like us, they prefer to watch screens filled with panicky propaganda that annihilates their critical faculties.

Here’s how one character, an aging professor named Faber, explains it:

Whirl a man’s mind around about so fast under the pumping hands of publishers, exploiters, broadcasters, that the centrifuge flings off all unnecessary, time-wasting thought … If you’re not driving a hundred miles an hour, at a clip where you can’t think of anything else but the danger, then you’re playing some game or sitting in some room where you can’t argue with the four-wall televisor. Why? The televisor is ‘real.’ It is immediate, it has dimension. It tells you what to think and blasts it in. It must be right. It seems so right. It rushes you on so quickly to its own conclusions your mind hasn’t time to protest, ‘What nonsense!’

This collective numbing of our hearts and minds has led most Americans to turn a blind eye to the astonishing cruelty of immigrant families being torn apart, to the gutting of programs intended to aid those in poverty, especially children, and the senseless enrichment of billionaires.

The most chilling confession in the novel doesn’t come from Montag, or any of the other firemen who burn books for a living, but from Faber, who is old enough to have witnessed the intellectual and moral decline of America.

“You are looking at a coward,” he tells Montag. “I saw the way things were going, a long time back. I said nothing. I’m one of the innocents who could have spoken up … but I did not speak and thus became guilty myself.”

That line stings me to read. It stings me to read because it’s true.