Advertisement

Commentary

Relief Is The One Stage Of Grief No One Talks About

At the age of 17, after her first blind date with my father, my mother breathlessly wrote in her diary that she’d met the man she was going to marry. Three years later, her prophecy came true, and my parents remained married for 58 loving and adventurous years. While polar opposites in some respects — my father was calm, steady, and self-contained, while my mother was volatile, forceful, and luminous — the two of them shared a conviction that living for the moment trumped planning for the future, and living a meaningful life mattered more than a moneyed one.

In his last couple of years, dogged by a series of acute and chronic illnesses, my father’s life became more and more constrained. My mother’s shrunk along with his, as he was increasingly confined to home and she was reluctant to leave him. But in his last months, though he was physically the weaker of the two, my father remained my mother’s champion and caregiver, repeatedly drilling my brother and me on how we were to protect her health and ensure her financial well-being.

But he didn’t bother with practicalities in his oft-repeated instruction to my mother. Once she was no longer tethered to him, he implored, she was to return to making art.

... no meaningful compromise is possible when you are accompanying someone to the end of their life.

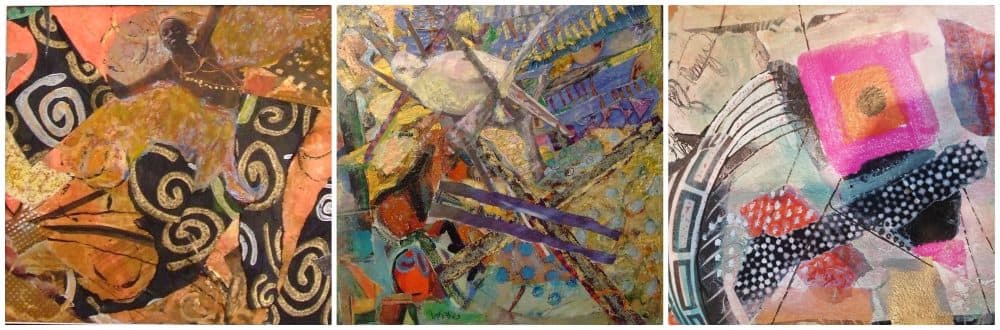

After his death, my mother held her grief close, rarely talking about it after the first few weeks of her widowhood. But she lost little time in signing up for a collaging class. And to her surprise, what emerged was not somber or dark. The work was colorful and vibrant, joyful swirls and playful juxtapositions of textures and images. My father had loved her creative energy, and she channeled that love in producing bold, often riotous canvases.

My mother’s passion for collage was in many ways a metaphor for who she was. The art of collaging lies in assembling seemingly disparate elements to create something entirely new, coherent and moving. She used to scour the sidewalk for smashed bottle caps, carefully peel off pieces of fading posters from city walls, collect handmade papers, cut and tear glossy fashion ads and National Geographic photographs, and then with glue and paint, bring them together in startling, evocative ways. As in her relationships with people, she favored the discards and scraps as much as the glossy pages, recognizing the potential in both. Collaging is the art of seeing possibilities, and that’s how she lived her life.

My mother was an anchor and a light. Her love for me was fierce, unconditional, and constant. So was mine for her. But caring for her in her last couple of years, her needs consuming more and more of my time, I felt the same enervating mix of sorrow, resentment, tenderness, and impatience that she felt in caring for my father. And despite my efforts to conceal my feelings, she knew it and never once reproached me for it. She’d tell me that of course, I needed to spend time with my husband, to exercise, to sleep, to write, and, oh yeah, to work. And then in the next breath, because dying is a long, scary, lonely process, she’d say that she needed me to be with her.

What I observed a decade earlier when she’d ministered to my father, then discovered myself when helping her, is that no meaningful compromise is possible when you are accompanying someone to the end of their life. You can’t find a healthy balance between tending to their needs and your own, not if what you need is to care for them. You scramble to keep all the balls in the air, but resignedly watch as one of them thuds to the ground, then another. You sleep less, eat badly, screw up at work, neglect your spouse, but do what needs to be done because you couldn’t live with yourself if you didn’t.

I felt the same enervating mix of sorrow, resentment, tenderness, and impatience that she felt in caring for my father.

Now that marathon is over, and I am making a dinner party for two of my oldest, dearest friends and their husbands. I’ve set the table with a daffodil-colored table cloth bordered by purple fleur-de-lis, the handsome brown-and-beige stoneware dishes that I pull out just for special occasions, and the glass cobalt blue goblets that my parents had brought back from France decades ago. I’ve made a meal of primary colors — tomatoes in shades of garnet and scarlet and rose, a salad of brilliant green snap peas with crimson radishes, dusky orange chunks of squash, and a cinnamon chicken kibbeh, its muted tones balancing the palette on the plates. Tomorrow, on my first free, non-caregiving or officially mourning day, I’ll go to the gym, then come home and write.

Thanks to my parents’ example, I’m giddily and guiltlessly reclaiming my life. But in doing so — in savoring color and taste and the company of people I cherish, in once again trying to create something new — I’m honoring and extending theirs. They imbued my brother and me with urgency to live every moment as fully as we could. It was their last and most generous act of love.