Advertisement

Commentary

The Kids Have Something To Say. We Should Listen

when you are waiting to die,

you lose your own adjectives.

you are no longer yourself.

you are a series of actions ...

i shook.

and i listened.

and i waited.

and i kept silent.

but now i refuse to stay that way.

this could have been prevented.

this can never happen again.

the numbness has started to crack

and i want my adjectives back

i want change

i want change

-- An excerpt from “the words” by Anna Bayuk, published in “Parkland Speaks,” edited by Sarah Lerner

***

CHICAGO — There were kids everywhere. Sprawled in the hallways on laptops and traveling in tight packs through the lobby and up the escalators. Four-thousand high school journalists gathered in a Chicago hotel for the National Scholastic Press Association’s (NSPA) fall 2018 conference.

Among the throngs were the student journalists from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. A year ago, these students hid in a closet for two hours as a gunman roved their campus, killing 17 and injuring more than a dozen.

On that gruesome day, before they knew if they would live or die, the team was already making decisions about how they would cover the story.

At the conference, Sarah Lerner, the faculty yearbook advisor, was delivering a 50-minute breakout session titled, “It’s Our Story To Tell.” Hundreds of kids had lined up outside a single doorway of a large conference ballroom with palpable urgency.

One girl, from a high school in Columbia, South Carolina, said she was there to learn what to do, as a journalist, when “this” — a shooting — happens in her school. It wasn't a question of if, only when. That was a common sentiment; part of being a kid in America today.

After the tragedy, the Parkland students could have been swept away in a tidal wave of panic and grief. Instead, Lerner described how they got back to work to help the world remember their friends.

The first anniversary of the Parkland shooting happens to fall two weeks before another important date: the 50th anniversary of Tinker vs. Des Moines, the Supreme Court case that declared students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Mary Beth Tinker was a 13-year-old middle schooler when she was suspended for wearing a black armband to protest the Vietnam War. Her family and the ACLU sued the Des Moines Independent School District on First Amendment grounds — and won, in a 7-2 decision.

Now in her mid-60s, Tinker is a living hero to the student journalists in Parkland. In fact, the MSD students will travel to Iowa in late February to cover Tinker anniversary events.

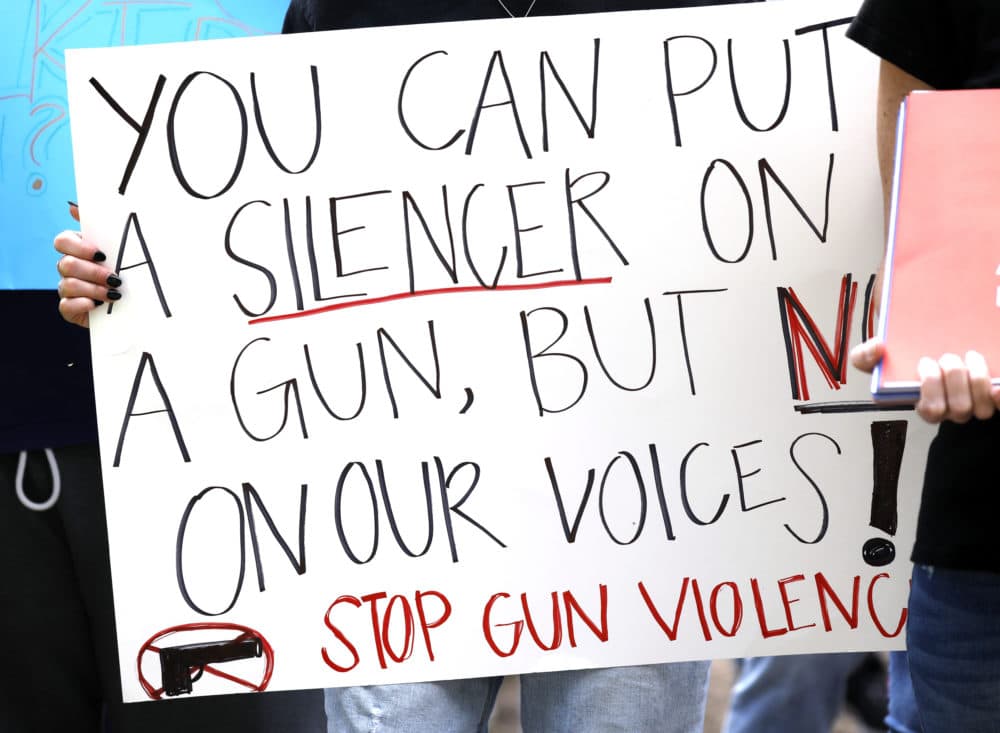

The administrators at MSD did not censor student coverage of the shooting. No one prevented the newspaper from running stories about guns and gun violence, or essays on the prevalence of fake news, or editorials about the undue influence of the National Rifle Association. They were able to provide intimate details about the kids who were killed, and cover the national movement against gun violence — March For Our Lives — born in their school.

When, hours after the shooting, conspiracy theorists started attacking student survivors as “crisis actors,” the young MSD reporters offered a competing narrative about the kids they’d grown up with.

But not all student journalists are able to fully exercise their First Amendment rights.

Massachusetts protects student speech under the Tinker standard — and has for some three decades — but 36 states (including Florida) have yet to pass legislation cementing kids’ rights to free speech, leaving student journalists vulnerable to censorship and “before-publication” review.

Kids all over the country are being muzzled by administrators. A school in Indiana banned students from covering a sexual assault on campus. A school in Utah prohibited students from investigating why a popular history teacher was fired. A school in Texas forbade students from publishing an editorial critical of administrators’ efforts to stifle participation in the National School Walkout to protest gun violence.

And this comes at a time when students are providing essential local coverage, thanks to an existential crisis in journalism, and are “especially vulnerable” to the president’s attacks on the press, precisely because they start out with fewer First Amendment protections.

There were 94 incidents of gun violence in schools last year, the most on record. Four-year-olds are practicing lockdown drills. If history is to be our guide, it’s only a matter of time until the next massacre. But there’s been some meaningful progress since Parkland, too: 67 new gun control laws were enacted and fewer pro-gun laws passed in 2018. A clear majority of Americans continue to support stricter gun laws. More politicians are campaigning and winning as anti-gun candidates. And maybe most important, the issue of gun violence has not receded into the shadows.

Unlike calls for change after Columbine, Virginia Tech and Newtown, the kids in Parkland seem to be changing the narrative. They’ve joined a legacy of young American activists who helped desegregate lunch counters, protest the Vietnam War and register voters in the deep south. Armed with iPhones, a native understanding of social media and a willingness to share their lives, they are marching and lobbying and organizing.

Back at the NSPA conference in Chicago, the Parkland student journalists and their advisors have some minor celebrity. They’re not immediately recognizable, but in polite conversation, when the time comes for a Parkland kid to say where they’re from, there’s a flash of recognition, usually followed by a flicker of awe or pity.

They may never get used to those looks. We can only hope they know they are more than what happened to them.

In a piece for MSD’s student newspaper, “The Eagle Eye,” editor-in-chief Rebecca Schneid, wrote:

“... it has often been the youth who begin the fight for social change ... grassroots activism by those who see the ailments in their communities is what leads to actual change. It is a bottom-up process and one that could take decades to see results, but persistence, perseverance and proficiency in the facts allows for the society to eventually address and correct injustice, making for a better society as whole.”

Mary Beth Tinker couldn’t have predicted that her protest in middle school would become a model of courageous activism to the survivors of a school shooting 50 years later, but there is a straight line between the two.

As we read again the names of the dead — Alyssa, Scott, Martin, Nicholas, Aaron, Jamie, Christopher, Luke, Cara, Gina, Joaquin, Alaina, Meadow, Helena, Alexander, Carmen and Peter — the power of young people, and those who honor their voices, is something to celebrate.

The kids have something to say. And we should listen to them.

Video is excerpted from a documentary project by Maribeth Romslo.