Advertisement

Commentary

My Family's Home Survived Nazi Germany, But Not Modern Life

In the suburb where I used to live, small family homes have been destroyed to make way for larger, grander houses with open concepts and quartz-countered islands, pendant lights and playrooms upstairs. Too many ranches and capes, with their dormered windows peeking onto the street, have ended up in dumpsters. The process is routine: A large excavator rolls off a flatbed first thing in the morning, and sometimes by lunch, has clawed an ordinary home to pieces, ripping off walls and windows and roofs.

Once I watched the demolition of a home nearby and witnessed the claw carefully tear away the entire facade first, leaving the inside open and vulnerable. It was astonishing to see the fireplace, bathroom fixtures and full kitchen, with cupboards, refrigerator and stove intact, awaiting the homeowners’ return that evening. Hours later, those home components were also in the dumpster, as if no one had ever cooked at that stove while children did homework at the table nearby.

When a lot was cleared, a house three times larger emerged in its place, often with five bedrooms and five bathrooms for a family with two children. Mansionization was a constant talking point in town, but the teardowns continued, unabated.

But the cottage, like my family, had a will to survive.

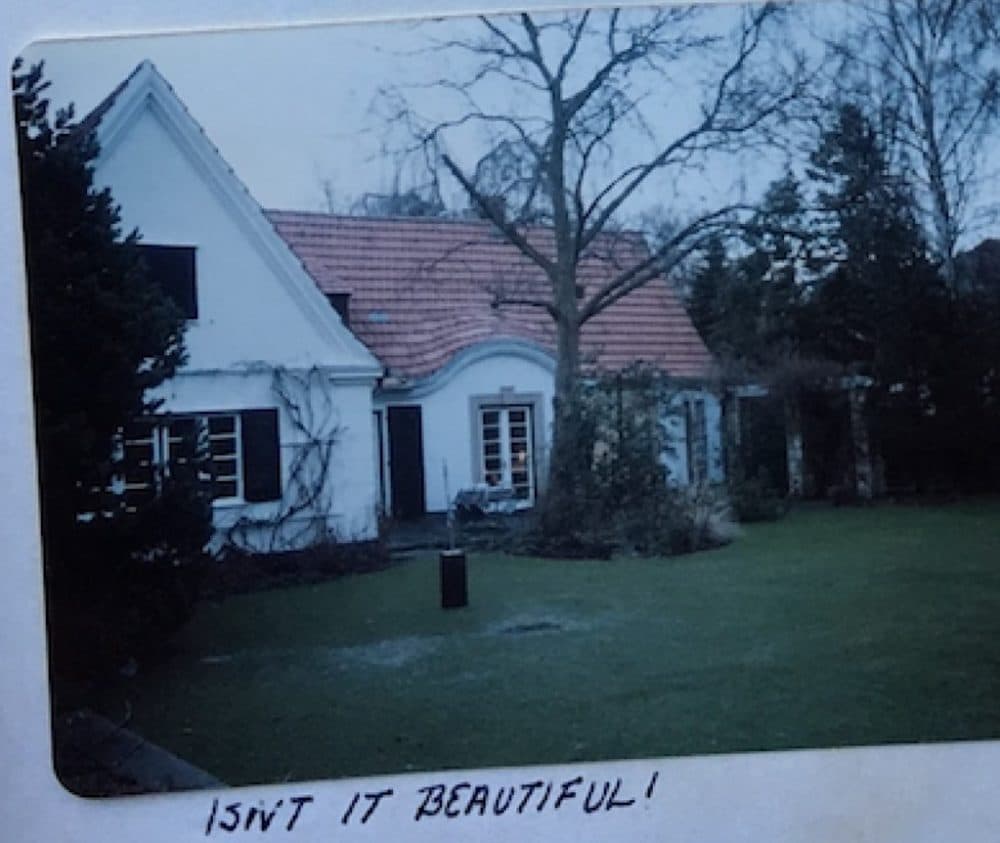

Just before we were grounded by the pandemic, my daughter Joanna and I traveled to Dahlem, the district in western Berlin where my mother was born. I was anxious to visit the sweet cottage where she had lived as a young girl, with its orchards of peach and plum trees, the gardens of dahlias and helenium and daisies — life before my mother and her family were forced from their homeland by the Nazis.

But the cottage, like my family, had a will to survive. Although my grandparents were forced to leave Germany with almost nothing, an English woman and her German husband, unsympathetic to Hitler, bought the Dahlem home, promising to deposit a fair sum of money in a bank in England. The woman, Christabel Bielenberg, wrote about this agreement in her book, "When I Was a German, 1934-1945: An Englishwoman in Nazi Germany."

Indeed, when my grandparents arrived in England, they found the money in a designated bank account, and the Bielenbergs later left the deed to the property in their name. Although so much had been lost, the family home survived the war. But by then, my grandparents and their daughters were living in America. They never returned to their former home in Germany.

Other family members have visited Dahlem over the years. After the Bielenbergs moved on, another couple lived in the home for several decades, and warmly greeted my sister and later my nieces, once they heard the story of our family connection. And now I, too, was finally going to experience this part of my ancestral history.

My daughter and I arrived by train in Dahlem and knew it was only a short walk to #30 Falkenried, the address of my mother’s former home. I had studied family photographs so often, I felt that I’d been there countless times before. But now after all those years, I was on the street with impatient anticipation, looking for the house. We walked up and down Falkenried twice, yet couldn’t find it. Recent Google Street photos depicted my mother’s former home hidden behind overgrown trees, so Joanna and I stopped looking for the cottage and started looking for orchards reaching the sky.

We found neither. The gardens and welcoming cottage with its thatched peaks were gone. It was easy to see why we had missed our #30. Gun-metal-toned numerals blended with a locked metal gate, protecting a sterile modern house with a flat roof. Just as in my former town, here the new owners had built a house more to their liking.

Joanna and I were heartbroken. I’d waited so long to take this trip, to make this connection with my mother’s past and our ancestry. And then this cherished home, saved by the Bielenbergs and another couple who had loved it just as my grandparents had, was destroyed.

I had studied family photographs so often, I felt that I’d been there countless times before.

I’ve thought so often about the meaning of home, which is much more than a physical structure of brick or wood. Home is a container of memories, a safe haven, a place where you feel secure. But my grandparents, like many victims of war and violence, lost that security when they were forced from their home.

A few years ago, my former husband and I sold the family home where we had raised our children. The new owners explicitly stated their desire to tear it down and build something larger and grander. It’s true that the house needed new kitchen cabinets. The bathrooms were outdated, as was the floor plan. But it was the home in which my children lost their first teeth, learned to ride shiny two-wheelers, the home where we had celebrated birthdays and graduations. My daughter’s bedroom door still had pencil markings commemorating her yearly growth. I can hear my grown son’s high school rock band practicing in the basement.

The last time I visited my former town, the house was still standing. I also know that one of these days, I may arrive and find it gone. But it is no longer my home, and the owners are entitled to build one more to their liking. However, even if the house is demolished, my memories won’t end up in the dumpster. I’m comforted knowing that my grandparents took memories of #30 Falkenried with them to America, just as I will take mine wherever I go.