Advertisement

Commentary

Is my family’s Holocaust trauma woven into my DNA?

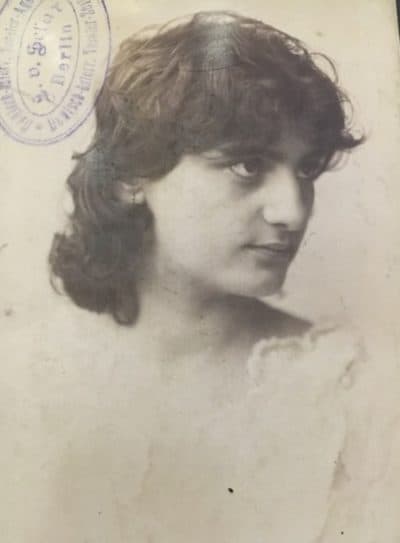

Treblinka's main stone memorial towered over me, surrounded by a landscape of boulders and rocks representing victims from various countries: Yugoslavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Germany. I'd been imagining this trip for years. Standing under the tall pines, I held a sepia photograph of my great-grandmother.

For decades, I knew nothing about this great-grandmother, not even her name. Gisela. My grandfather, Otto, refused to talk about his mother, so she was hidden in the vault of family secrets. I understand now that Otto’s pain was unbearably deep; late in his life he finally revealed this "thorn in his heart." In June 1939, after an interminably long wait and great expense, my grandfather had been able to secure only four visas to England for his five-person family. He was forced to make an awful "Sophie's choice": Take his wife and daughters — or his mother. He left Gisela behind and planned to send for her once they were settled in the United States. But by then the war had started. No one in our family ever heard from Gisela again.

Otto died before we knew exactly what had happened to her. Ten years ago, my sister discovered our great-grandmother’s name on the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum survivors and victims database. We learned that she had been transported first to Theresienstadt, and then to the death camp of Treblinka three months later. We identified the exact dates, the exact number of people in each transport. My great-grandmother was close to 70 years old and by herself. This alone causes a thorn in my heart.

Since learning of Gisela’s fate, I've felt a visceral need to stand on that particular ground under those pines, the ground on which my great-grandmother lost her life. I didn’t know then that I carried her trauma in my DNA.

***

From the time I was young, I was anxious and especially afraid of enclosed spaces. This fear escalated in third grade, after a science lesson about underwater life, accompanied by a grainy filmstrip on bathyspheres, round deep-sea submersibles that crawled along the ocean floor. I began suffering from suffocation dreams, avoiding elevators and hide-and-seek, but I kept my worries to myself. I learned to accommodate my fears as I grew up, knowing, for example, that I needed to rent apartments with dedicated parking to avoid walking down dark streets at night.

After a while, I became used to these compromises and barely thought about them, except in retrospect.

Once I learned about my great grandmother and how she’d died, my nightmares intensified. I often dreamt of heat and oppressiveness, of too many people crammed in dark, enclosed spaces. Pushing. Breathless. I could feel Gisela’s claustrophobia, my claustrophobia. In my dreams, she and I were often smothered.

But I always woke up. Anxious and short of breath, but I always survived.

I began to study Rachel Yehuda’s research on epigenetics, findings which reveal the ways trauma is inherited, how it significantly changes the genomic DNA of Holocaust survivors for four generations. According to Yehuda, Holocaust offspring have the same neuroendocrine or hormonal abnormalities of Holocaust survivors and persons with post-traumatic stress disorder.

More recent investigations suggest that Yehuda's conclusions were premature. Yehuda acknowledges that her sample of Holocaust survivors was small, and studies in mice, while offering evidence of trauma transmission, do not translate well to humans.

Intuitively, I felt that confronting the atrocities of Treblinka was one way to heal, to protect my children and their future children.

And yet. My lifelong claustrophobia was real. Most members of my family also suffered at one point or another from anxiety, which made sense in the context of Yehuda’s research. This connection to Gisela’s trauma, to that of my mother and grandparents, who were forcibly exiled from their homeland, did not seem like coincidence, despite the arguments of scientific critics of epigenetics. I read further. Yehuda posits that healing the effects of trauma in the present can prevent it from echoing into future generations.

Intuitively, I felt that confronting the atrocities of Treblinka was one way to heal, to protect my children and their future children. People questioned traveling to Poland solely to visit a death camp memorial. But I knew it was what I needed to do.

We listened as our guide Jacek described the significance of the carefully laid cement blocks beneath the pines, stretching half a mile. “When building the memorial,” he told us, “the artists wanted to symbolically represent train tracks, the ones that brought prisoners right into the camp. "Those stones,” he said, pointing towards a flat area, “represent the platform, which was disguised as a transit station.” I thought of my great-grandmother, disembarking from an oppressive cattle car and seeing signs marked with different destinations, designed to trick her and the other prisoners. I hoped that she was similarly unaware when directed later towards what she believed was a bathhouse.

I whispered her name. Gisela. An actress. A mother. My great-grandmother.

We walked the grounds of Treblinka for over two hours. At first I was tense and teary. But in time, a calm descended strangely, peacefully. In the distance, I'd noticed a lone tree, pushing up amidst the memorial rocks, growing as if dared not to seed there. Hope. There is always hope. I whispered her name again.

Gisela.