Advertisement

Harvard Forum: Should Older Politicians And Judges Be Tested For Mental Decline?

The speculation spreads every time an older politician of either party blunders verbally or seems to lose the thread: Is it Alzheimer's? Early dementia? Impaired judgment?

Professor Francis Shen of the Center for Law, Brain and Behavior shared a crop of typical headlines at a Harvard Law School Petrie-Flom Center forum called "Dementia and Democracy" this week. They included politicians of various stripes targeted by weaselly phrases like "may have Alzheimer's" and "may have early-onset dementia."

He followed them up with a slide pleading in huge letters: "Surely we can do better than this."

Shen's central point: Politicians, who have huge advantages as incumbents, and federal judges, who serve for life, tend to stay on the job well past typical retirement ages. Yet we know that some cognitive decline with age is normal, and that the risk of dementia skyrockets as we get older.

So it's reasonable to conclude that some judges and politicians are no longer up to their tasks. But their cognitive failings can often be very difficult to pin down. (Recall the murmurs about President Reagan, who was later diagnosed with Alzheimer's.) Hence the headlines.

So what is to be done? Calling all high-school debate coaches. On older politicians, Shen offers a range of options:

• We could continue with the status quo and just hope that the political scene detects and deals with cognitive decline.

• We could require testing for cognitive decline and disclosure of the results.

• We could seek expert diagnoses based on publicly available data, such as speeches and videos. (Example: STAT News examined President Trump's changed speaking style.)

• Congress could pass a "bright-line" age limit. For example, it could rule that no one over 75 could run for re-election. (That would rule out, among many others, California Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who is running for re-election at 84, saying "I'm all in!")

For federal judges, Shen also adds the option of a "rebuttable presumption," meaning that when they reached a certain age, judges would have to demonstrate that their minds are functioning well enough for them to stay on the bench.

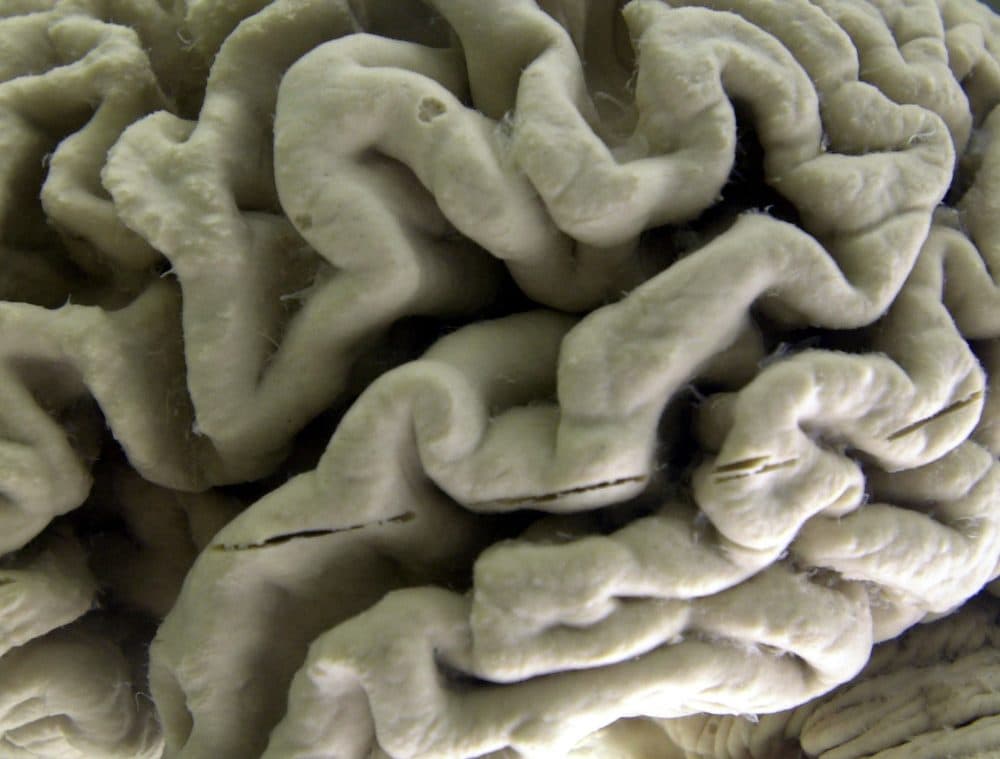

Lest anyone protest that even raising these issues is ageist, Dr. Bruce Price, a leading neurologist at McLean Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, shared persuasive data on the brain effects of aging.

Research suggests that probably 10 to 20 percent of us don't age much at all in terms of our cognitive performance, he said. But normal aging does involve some cognitive decline — mainly in "fluid intelligence" qualities such as processing speed and working memory — and near lifespan's end, "mild cognitive impairment" and outright dementia dominate.

Advertisement

Clearly, no politician or judge with full-on dementia can fulfill their duties, but below that level, the slopes are slippery. As Shen pointed out, "We don't have great publicly available metrics" on how well judges and politicians perform cognitively.

Compare that to the plentiful metrics in sports, he suggested. Take 40-year-old Patriots quarterback Tom Brady: "We can look at how quick his reaction time is, and has it dipped year to year?" With judges, "We don't really have that ability from the outside to determine: Are opinions a little less concise than they used to be? Are oral arguments?"

We're left to guess, he said. So why not test? First and foremost, though cognitive testing for Alzheimer's and other disorders does exist, there are no widely accepted professional tests for whether, say, judges are losing their judicial edge.

Basing diagnoses on publicly available data is also extremely problematic — as witness the recent raging controversy over whether it's acceptable for psychiatrists to translate Trump's behavior into formal diagnoses in an attempt to warn the public.

Diagnosis is not the point anyway, argued Dr. Rebecca Weintraub Brendel of Harvard; ability to function is: "We have got to separate this discourse of capacity — the ability to perform functions of public service — from a discourse of mental illness or neurologic illness," she said.

And there's a major pitfall here, she warned: "Even if some abilities do decline, others might be critically important. So if you do have mandatory retirement ages in professions that are highly dependent on experience you also lose the perspective of those who have seen a lot and can contribute, even though how they contribute might be different."

On the other hand, some professions — commercial airline pilots, for example — do have mandatory retirement ages. A case could be made, Shen said, that judges and elected officials fall into a similar category, given the impact of their decisions.

But he does not support "bright line" age limits. In an email after the Harvard forum, Shen called for a careful middle way:

The experienced mind is a precious and rare resource, and that is all the more true for judges and politicians. We thus need to ensure that wisdom remains on the bench and in legislatures. Mandatory retirement ages are too blunt and arbitrary an instrument to accomplish that.

Requiring cognitive testing above a certain age is appealing, as it would allow us to identify those in law and government who have lost the requisite functional capacity. But we need to administer the testing with an emphasis on privacy and graceful exits. If we’re thoughtful about our testing procedures, we can accomplish this. Wisdom should prevail, but dementia should not be demonized.

Readers? Do you agree? What do you think should be done?