Advertisement

The Price Of Health

This Mass. Woman Has 2 Insurance Plans. She's Still Struggling To Pay For Prescriptions

Resume

Pretty much every week, Joanne Rhoton drives herself to the drug store near her Everett home where she and the pharmacist are on a first-name basis.

“She's very nice, Lucy. I love her,” Rhoton says. “I call on the phone, she recognizes my voice, too. 'Joanne is this you?' 'Yeah, it's me.'”

But like most people, Rhoton doesn’t have such nice things to say about the drug companies that make her prescriptions.

“I think that the drug companies are getting too big for their britches,” says Rhoton, who is 73. “I think they need to have some kind of humanity going on in there.”

A new WBUR poll finds that although the vast majority of Massachusetts residents have health insurance, nearly one in three who’s filled a prescription in the last year has struggled to afford it. More than one in four reports skipping doses or rationing pills because of concerns about cost.

Rhoton has already spent $1,200 this year on prescriptions — $348 treating her diabetes and the rest on pills for her thyroid, blood pressure, high cholesterol, depression, insomnia and an inhaler to help her breathe better. A recent trip to the pharmacy left her with a $159 bill.

“So that's a good healthy feeding of my charge card, don't you think?” she asks.

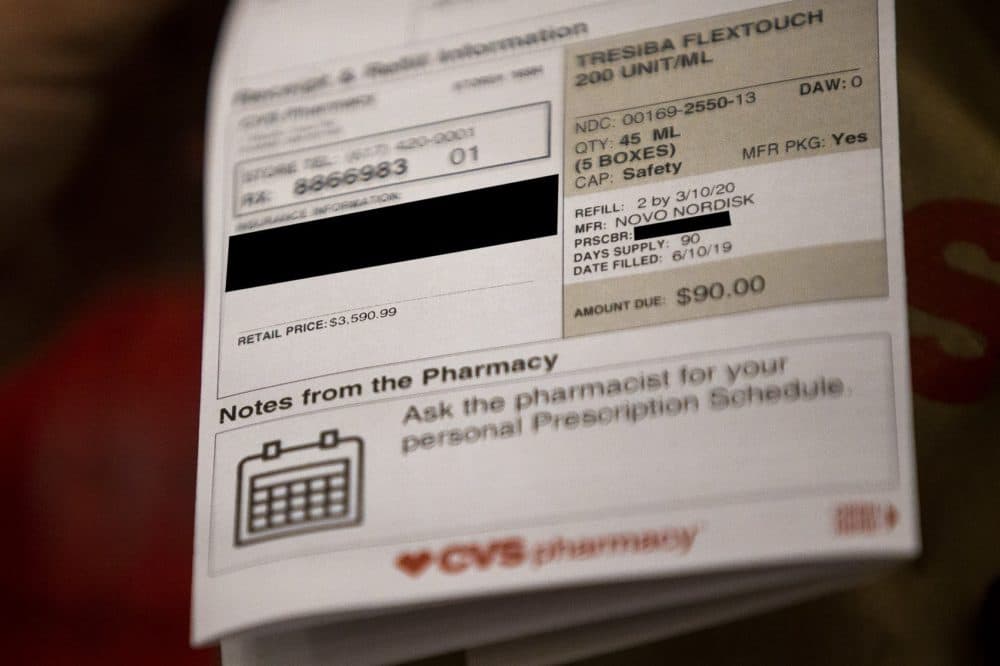

Rhoton is luckier than some patients. Since her ex-husband died, leaving her with higher Social Security benefits, she’s been able to supplement Medicare with secondary insurance, bringing her costs way down. Without either insurance, the $90 she was recently charged for insulin would have been more than $3,500.

“Is that incredible? I mean that's almost laughable, isn't it?” she says after looking at the figure.

Rhoton carefully tests her blood sugar three to five times a day, and balances it against what she eats and how much she exercises.

“When you have diabetes, it affects every organ in your body. So you have to take care of your body,” says Rhoton, who was diagnosed in 1995 with the adult-onset form of the disease.

Price isn’t Rhoton's only challenge. Medicare and her insurance company decide what brand of insulin she can use and what monitoring system – and sometimes they change those decisions. Rhoton had to adjust to both a new drug and a new blood sugar monitor in the last few years.

“I think that the drug companies are getting too big for their britches. I think they need to have some kind of humanity going on in there.”

Joanne Rhoton

“So, they're like sort of dictating what a person can get and can't get. You can't shop around because they got the call on it, you know what I mean?” she says. “Medicare has said these are the only ones that you can have. So that's all you can do.”

It’s a common problem. In Massachusetts, more than one-third of those who have recently taken a medication have been told their insurance wouldn’t cover a drug prescribed by their doctor, according to the new WBUR poll.

Rhoton cuts corners where she can to try to save money.

She reuses her needles to make them last longer. She says she knows of one man who used the same needle for a full year. But they get dull fast – and then hurt going in.

“They're really expensive,” she says. “But I got a serious infection in my stomach because you can't — you're not supposed to do that. You're supposed to, you know, change ‘em every time,” she says.

Rhoton also has saved money by getting extra supplies from friends and relatives. A neighbor gave her needle-tipped pens she uses to inject insulin.

“And also, when my aunt died she had some. So, I got hers. And my cousin died. I got his,” she says.

Still, sometimes she rations her insulin to make it go further.

“I'm supposed to take 54 units in the morning and 48 units at night. So, what I might do is just take 50 in the morning and then just take 40 at night,” she says. “But then I wake up with high blood sugar, so that's not good.”

Rhoton doesn’t feel like she can afford to do things the “right” way.

“When you're up backed up against a wall, I mean, you have to do something,” she said. “And I'm sure that I'm not the only person that has diabetes that is doing this sort of stuff.”

She’s not. In a recent study out of Yale University, one in four patients reported rationing their insulin because of cost. And almost one third of the respondents in the new WBUR poll said they know someone who’s struggled with the cost of insulin.

Shortchanging insulin can be dangerous, says Bob Gabbay, the chief medical officer at Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, where Rhoton gets her diabetes care.

“It's enough to prevent them from their blood sugar getting really high and ending up in an emergency room but not enough to control their blood sugars as well as they could be,” he says.

Gabbay says he’s not sure how many of his own patients struggle to pay for insulin. It’s a difficult conversation to have.

“It often takes a little bravery on their part to be able to share that because for many people, it's a bit embarrassing to have to talk about their inability to afford things,” he says.

But there’s no question, he and others say, that keeping blood sugar levels stable is essential for patients’ health long-term.

“They can reduce their risks of heart disease and stroke and blindness and kidney failure and amputations dramatically — more than 50% for sure,” said David Nathan, who directs the Diabetes Center at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

These diabetes complications are hugely expensive – “of course in human terms, but also in financial terms,” he says. “So that the better that we are able to prevent those complications, the better we can reduce costs overall and human costs in particular.”

Financial pressures, he says, just make it harder for diabetes patients to care for themselves.

“Every moment of every day is affected in some way by their having diabetes – it affects their eating, how they have to test their blood sugar, and of course giving insulin,” he said, so any further complication, like struggling to pay for medications, “is really potentially devastating, on top of all of the other pressure they have.”

Rhoton said she’s just grateful that her financial picture is more stable now than it used to be, thanks to her ex-husband’s benefits.

“I don't know how I did it. God was with me. That's all I can say is, God saw me through and He just took care of me when I couldn't take care of myself.”

This segment aired on June 24, 2019.