Advertisement

At 'Intersections' From Roxbury To Andover, Students Stand Together For Gun Control

Boston-area student-activists lobbying for gun control this month acknowledge an inconvenient feature of the national debate they’re getting into: There isn’t just one “gun problem” facing young people in America.

In the popular consciousness, the age of school shootings is remembered by the names of the more affluent communities — Columbine, Newtown, now Parkland — that have witnessed multi-victim massacres since 1999. And yet, many times more young people — usually young people of color — are killed in urban areas like Boston, typically with handguns.

That fact wasn’t lost on 16-year-old Evelyn Reyes, a sophomore at the John D. O'Bryant School. Reyes, the daughter of a Honduran immigrant, is a member of the Boston Student Advisory Council (BSAC) — the official body for student leaders from Boston Public Schools (BPS), co-administered by the district and the nonprofit organization Youth on Board.

Reyes lives in Roxbury, a community which she said has seen more than its share of that second type of gun violence, though it has always taken place at the periphery of her own life.

“I’ve been in class while there’s been a shooting around my school — on the street behind the school,” Reyes remembered. “I’m seeing all of this stuff around me.”

BSAC leaders hoped to bring their urban experiences to a debate that has, primarily, focused elsewhere. Reyes, for one, said she couldn’t sit by as young people stood up against guns: “All of those shots are landing somewhere. If I can stop that, then I will.”

The BSAC students represent the state’s largest school district — and the one with the most gun-related incidents. They feel out of step with the national conversation around gun rights — but, as they found out during a March 14 day of action at the State House, not with their peers from wealthier suburban communities.

And they agreed that this spring’s marches can allow students too young to vote to communicate those concerns to leaders who might not otherwise hear them. “We need to build a bridge between policymakers and students,” Reyes said, “so they know what our experience is. Otherwise, you’re just making policy blindly.”

Many Boston students' plans to confront policymakers were dampened by snow on the day of the rally. Some groups gathered at their schools, but the Beacon Hill crowd was visibly dominated by students — mostly white — from other parts of Greater Boston.

Reyes, who was scheduled to speak at the State House, noticed right away: “I was like, ‘Whoa. It doesn’t look like a BPS kids group,’ ” she said afterward.

It could pose a challenge of representation — except that many rally participants took pains to show solidarity with students hailing from very different environments.

“I don’t want our schools to become a prison,” said 14-year-old Laura Lewis, a Medford middle schooler. “I feel like I am safe [at school] — and I want that to be true everywhere,” gesturing both at the urban context and beyond Massachusetts’ borders.

Those fissures — between urban and suburban contexts — were strewn throughout students' conversations and speeches. Student organizers were specifically pushing for two gun-control causes — a bill that would allow the state to temporarily confiscate weapons from people deemed an "extreme risk," and the legal defense and enforcement of the state's 20-year-old assault-weapons ban.

But leaders encouraged participants to ask lawmakers to support an ambitious education-funding bill as well — the better to pay for counselors and other supports in poorer districts.

Democratic Sen. Pat Jehlen spoke to students from her Somerville district in the hallway outside her office; a predominantly white crowd of teenagers gathered on marble stairs.

Jehlen — who is sympathetic to the movement and its goals -- praised the students' rhetoric for its comprehensiveness: "One of the many things that makes me hopeful is the way that kids from Boston — who experience gun violence in a really different way than the kids in Parkland — those kids are standing up, and you're standing with them. ... That's enormous."

When her time to speak to students and legislators in the State House's Gardner Auditorium came, Reyes spoke of the role gun violence plays in a story of two Bostons she grew up learning: "Systemically, communities like the North End and Jamaica Plain are painted as perfectly serene places, while communities like Mattapan, Dorchester and Roxbury are generally seen as extremely dangerous — not places you would want to visit."

Reyes' address was greeted with a standing ovation. She was followed by Charlotte Lowell, a senior from wealthy Andover who helped lead the rally.

In her speech, Lowell hit those same notes: "The epidemic of gun violence in this country can no longer be ignored or pushed aside. For too long, students — and especially students of color — have been dismissed and disregarded." The crowd answered with a chorus of snaps, signifying agreement.

Lowell went on: "We need education to be funded equitably. Education lies at a vital intersection between gun violence, school funding and economic justice. And without education, we can't learn how to use our voices." More snaps.

That key word — imagining issues and experiences of race, class and gender as not separate, but "intersectional" — was coined in 1991 by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw. It has made its way into activist discourse only recently, but it may be a generational rallying cry. At least according to Reyes: "That's sort of a Gen Z thing... We know how to manage intersections of people and problems."

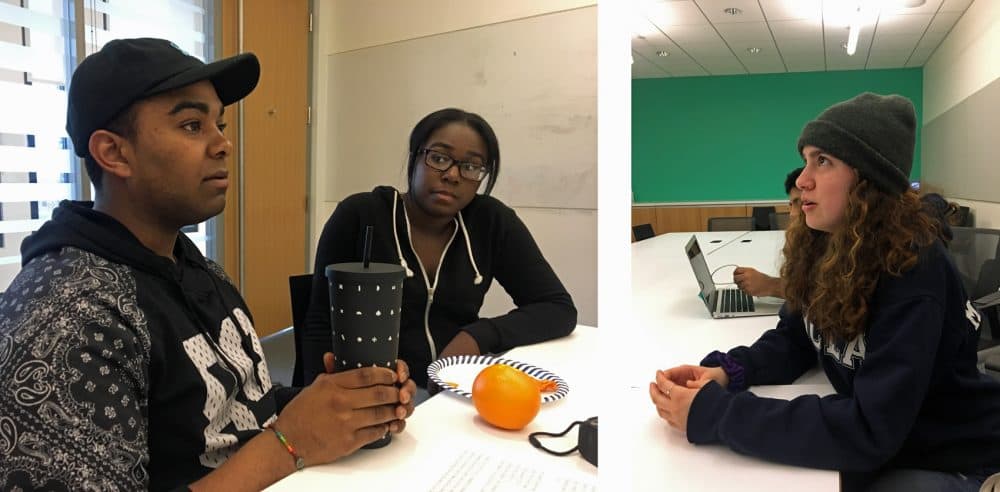

Other BSAC members, speaking at a February meeting, agreed. The same week that President Trump referred to the accused Parkland shooter, Nikolas Cruz, as a “coward” and a “maniac," senior Keondre McClay spoke in terms of the “social trauma” that might drive a young person to take up arms.

“What jobs do they have access to? What after-school programs do they have? Do they have equal access to housing? What [resources] have been provided for dealing with all that?” McClay asked, craned over a laptop reading “Counselors, Not Cops.”

“We’re pressuring people to put more systemic supports in place,” he added.

The American School Counselor Association recommends districts employ one counselor for every 250 of its students, but only New Hampshire, Vermont and Wyoming are meeting that standard. Massachusetts’ ratio in the 2014-'15 school year was 423 students per counselor. According to advocacy group Educators For Excellence, the balance is even more lopsided in Boston — with one counselor for every 1,272 students.

Last month, BPS superintendent Tommy Chang told WBUR that he believes the district “absolutely has the resources and support services needed for young people.”

BPS’ latest budget — drawn up before the Parkland activism — calls for a 3.7 percent cut to the line item for psychiatric and pupil adjustments services: from $69 to under $66 million. At the same time, it proposes for a 3.5 percent increase in the district’s “safety” line item, to $114 million.

A BPS spokesman declined to comment.

BSAC members warned specifically against further "hardening” Boston’s high schools.

The status quo is hard enough as it is, Reyes said. When she sees police officers carrying weapons during the school day, she said she wonders, “Do you think you’re ever going to use those in my school? Please don’t!”

The police officers who work in Boston Public Schools aren’t armed. But according to a district spokesperson, 19 Boston high schools do use metal detectors.

Reyes doesn’t disapprove of stationing officers in school buildings. But, she added, that doesn’t mean they feel like a resource to support students: “How many of those officers are trained in restorative-justice practices? How many are able to deescalate a situation, rather than just restrain a student?”

Next year, BPS will partner with Sandy Hook Promise — a group founded in the wake of the 2012 shootings in Newtown — to create a way to report any worrisome signs, securely and anonymously, to a full-time staff of crisis counselors.

Reyes said she appreciates that the fight to get guns out of communities like Roxbury will be a long one: "Every racial difference that exists in this country is playing into this." She mentioned recidivism, racism and poverty as forces that prevent some of her neighbors from peaceful participation in Boston's civic life.

In the long term, Reyes said she feels "trapped" by the fact that neither the sitting president nor the opposition Democrats seem determined to tackle those structural problems. But she added that for now, she will keep trying to offer her own intersectional call for change.

"The problem is these situations [of gun violence in the urban core] have been normalized. There's no big deal about it on the news," Reyes said. She and other Boston students plan to attend a Harvard event Tuesday night with activists from Parkland and participate in the "March For Our Lives" Saturday.

Reyes was humble about the warm reception she received at the State House. But looking back at the day of action, she was moved: "It hit me hard. It was great to see so many people, all in the same place, talking about the same thing."

This article was originally published on March 20, 2018.