Advertisement

Pass/Fail

Stark, Stubborn 'Achievement Gaps' Persist 25 Years After Education Reform

Resume

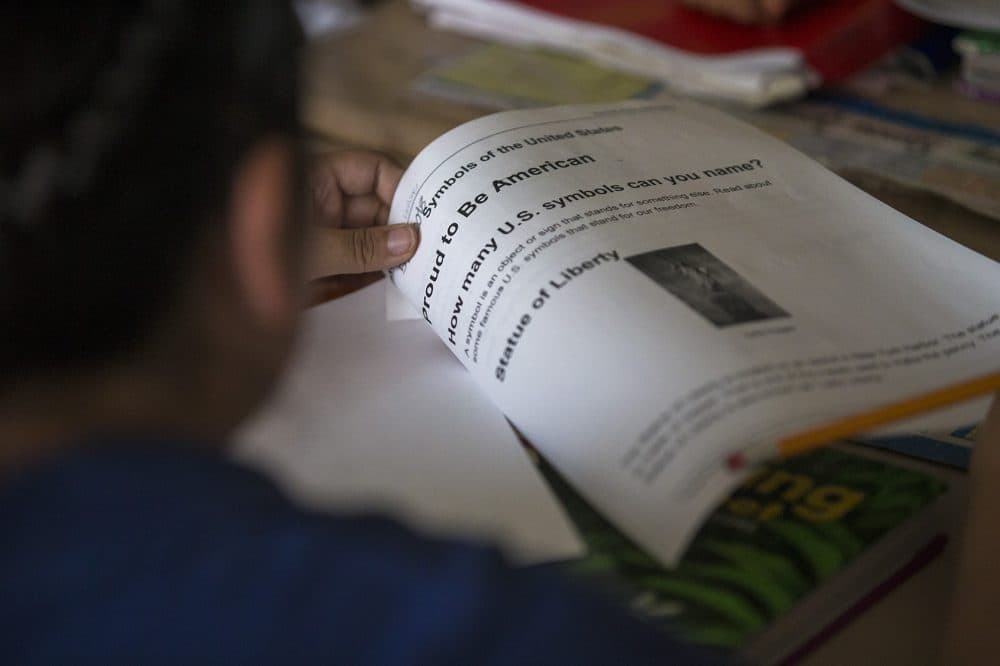

In a third-grade classroom at Garfield Elementary School in Revere, Penny Kalliavas has gathered a reading circle to talk about the Statue of Liberty.

"Over the years, immigrants arrived to begin new lives in America. To them, the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of all their hopes and dreams," she explained.

The lesson speaks to Kalliavas' students, about half of whom say they were born in another country. When asked who speaks English as a first language, only a few hands go up.

Migration is quickly changing Revere, as it has changed other Massachusetts communities like Lawrence and Holyoke over the past three decades. And that change could call into question what state education officials are measuring when they ask newcomer students to take a standardized test.

Corbett Couts, the principal of the Garfield, says students from different countries enroll every week: El Salvador, Colombia and Cambodia are well-represented among the new arrivals. And once a student has been in the United States for a year, he or she is supposed to take the MCAS.

This past spring, most of the students in Kalliavas' class took the English-language MCAS test for the first time.

Like Joshua Mendes and Anthony Ramos. Each arrived in the U.S. a few years ago. Mendes' first language is Portuguese. Ramos grew up speaking Spanish.

They said they felt nervous about taking the MCAS. Mendes said he sensed it was a "big test," and Ramos said he worried about having to repeat a grade.

The challenges and stresses of taking a major exam in a new language is not lost of Kalliavas.

"Oh my gosh, if I had to take a standardized test in a language I didn't know, I would be anxious and worried and scared," she said. So Kalliavas tries to manage her students' nerves.

"In the long run, it doesn't make up who they are. It doesn't make up their success," she explains to the mostly 8- and 9-year-old students. "It's just, kind of, like a measurement."

Kalliavas is not alone among Revere's multilingual teaching corps.

Downstairs, a fourth-grader named Sofia said her parents fled violence in Venezuela, and that her sister died as an infant. Then, she moves on to the English MCAS, saying: "Math is more easy."

One of the classroom's two ESL teachers, Adriana Nasteri, shakes her head: "We joke around about it. We say, 'Welcome to America; now take this test.' "

Measuring student performance was a principal goal of the 1993 Education Reform Act — marking its 25th anniversary this week. The text of the law requires the introduction of academic standards,

...which lend themselves to objective measurement, define the performance outcomes expected of both students directly entering the workforce and of students pursuing higher education, and facilitate comparisons with students of other states and other nations.

Today, many of the architects of the reform stand by that reasoning.

"Unless we test, we don’t have any way to determine whether we’re succeeding or failing in our education," said former state Senate President Tom Birmingham. Birmingham was one of the bill's authors; he is now a senior fellow in education at the conservative-leaning Pioneer Institute.

The idea was that low scores on the test would signal to district and state leaders that schools needed extra help, whether through funding or extra attention from the administration.

MCAS And Latino Students

At first, many people in the Latino community saw that approach as promising — at least as tolerable.

Why?

"Because it couldn't get any worse. The dropout rates were through the roof," UMass Boston sociologist Miren Uriarte recalled.

"I'm all for accountability. But let's all be accountable — not just the kids."

Sociologist Miren Uriarte

Uriarte had already been studying Latino students in Massachusetts when lawmakers started discussing reforms in the early 1990s. She was glad the legislation would pump $2 billion over 10 years into schools, especially in the state's poorest districts.

And as a researcher, she liked the idea of having solid numbers from the MCAS test.

But eventually the reform lost its way, Uriarte said.

The students she studies posted "dismal" test scores in the beginning, and the gap has lingered. In 2014, just 27 percent of English learners met state standards on the math MCAS — and just 24 percent on the English MCAS. By contrast, 60 and 69 percent of all state students met those standards that year.

That pattern has been visible for a long time. But rather than helping those students and their teachers with policies and resources to help them improve, Uriarte says the state ended up entangling them in a political web.

In 2002, Massachusetts voters passed an initiative that forced all that state’s students to learn in English only — an approach called “sheltered-English immersion.”

“It was really sold on on very shaky scientific grounds,” Uriarte said, noting that contemporary research suggests that most children take an average of seven years to learn academic English.

English learners have continued to lag behind their native-born peers on the MCAS test. That 2002 law is now widely regarded as a policy failure. The Legislature finally replaced the immersion requirement last year.

The story continues below.

State Takeover

Then in 2010, Gov. Deval Patrick signed a new education law with the stated aim to close the achievement gap. That law put the poorest-performing schools at risk of being taken over by the state.

Today, the state is running three entire districts — Lawrence, Holyoke and Southbridge. All of them are majority Latino districts. And the track record for that kind of state control is mixed. Both nationally and in Massachusetts, state receivership often involves mass layoffs of teachers or school closures.

Of the past seven years in particular, Uriarte says: “You know, I'm all for accountability. But let's all be accountable — not just the kids."

There are some districts in the state which have made progress in closing the achievement gap for English learners.

Boston has expanded its international school to include a "newcomer's academy," known as BINcA. And in Revere, educators have managed impressive MCAS scores given the district's rapidly changing demographics.

Revere administrators would argue that’s because teachers like Kalliavas are focusing on everything but test prep. The Garfield Elementary alone has added emotional supports and another ESL teacher to cope with the change in student population.

Revere even has a “newcomer’s academy” of their own, where immigrant students of all ages are brought together to play games, speak and learn in both languages. When we visited, a teacher and principal were modeling different clothes, so kids could learn the English names for them.

That approach seems to be working in Revere. It's unclear yet if it translates to other contexts.

Uriarte says it's an argument for getting beyond the idea of "objective measurement" and embracing teaching that is sensitive to students' starting points, no matter how various. She credits the Margarita Muñiz Academy, Boston's dual-language high school, for taking Latino students' culture and identity into account — so that they feel "much more comfortable than they do in other types of schools."

And the English-learner achievement gap is far from the only one at play in Massachusetts: The warping effects of income, race and disability still show up in test scores, as our interactive chart reveals.

The 1993 education reform law demonstrated in stark terms that those gaps persist. But it didn't close them. For many education activists, legislators and teachers, state leaders will need to try something new — and similarly ambitious — if they hope to make progress where so many efforts have failed.

Join our Facebook group to continue the conversation with other parents, teachers, administrators and WBUR's education reporters.

This story has been updated for clarity. A previous sentence could have been misinterpreted to suggest that state receivers closed schools in Holyoke, Southbridge and Lawrence. The sentence has been reworded to be more clear about the national context surrounding school takeovers.

This segment aired on June 19, 2018.