Advertisement

LSAT Or GRE? Some Law Schools Say Giving Applicants An Option Improves Diversity

Resume

Soon-to-be Harvard Law School student Olivia Castor says she has "strong feelings" about the Law School Admission Test, or LSAT.

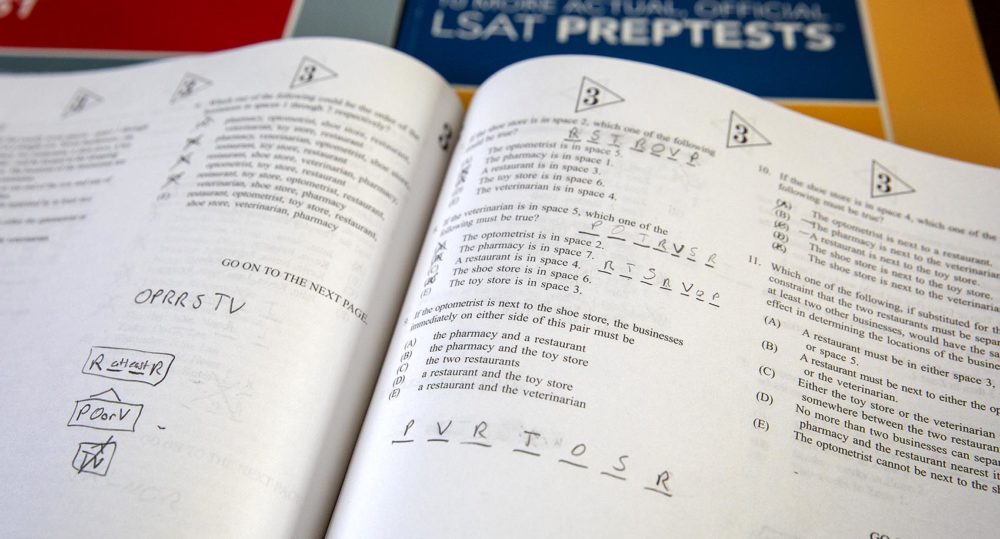

First, it was expensive. She dropped about $300 on prep books and practice tests and paid about $2,000 for private tutoring.

Castor took the LSAT last summer and says for about four months preparing for the exam practically took over her life.

"I studied March through June — Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday. And then on Saturday I would do a full length test," she explains. "So I was studying around the clock, and at that point I was also working full time."

But it wasn’t just the expense and time that Castor struggled with.

"When I first started studying I had no idea what I was doing," she says. "And I didn’t have any friends who were also studying for the LSAT."

Both of Castor's parents are immigrants, she explains, and there weren't any lawyers in her immediate family to ask for advice, so the whole process felt intimidating.

"I was just kind of blindly studying," says Castor.

A Shift To The GRE

It’s experiences like this that pushed officials like Marc Miller, the dean of the University of Arizona Law School, to look for other standardized tests, like the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE), to use in admissions a few years ago.

"We went with the GRE," he says, "because it’s so familiar and is now a basis for admissions to many different kinds of graduate programs and to business school."

In 2016, the University of Arizona became the first accredited law school to offer applicants the option to submit a GRE score instead of an LSAT score. At the time, the move was considered pretty controversial.

The American Bar Association's accreditation standards require a "valid and reliable" standardized test for admissions, and for decades, law schools assumed that meant the LSAT. Opening admissions to another type of test was a break with more than 60 years of tradition.

Legal publications criticized the move at first, saying diversity goals were just a cover, and the GRE policy was really about increasing revenue or filling more seats. But then, about a year later, Harvard Law School announced it was enacting the same policy.

"Accepting the GRE is part of a larger strategy here in our office to be constantly innovating and thinking about ways to make a Harvard Law School education more accessible to any applicant," says Kristi Jobson, the assistant dean for admissions.

The need for more diversity in the legal profession is something she takes personally.

"As a practicing attorney myself and as a woman in the profession, I can tell you riding the elevator up a fancy New York City law firm, you feel it," she says. "And walking down the courtroom hallway, you feel the lack of diversity in the profession."

About 85% of lawyers in the U.S. are white, according to the American Bar Association, and the numbers have barely budged over the last decade.

That may be part of the reason why today, about two dozen law schools have followed Harvard and the University of Arizona's lead and now accept GRE scores in admissions, in addition to the LSAT.

How The GRE Option Improves Diversity

So how does a test improve diversity? When you talk to admissions officials like Miller and Jobson, some of it boils down to simple logistics. The GRE is offered almost daily at thousands of testing centers across the world.

The LSAT, however, is not offered everywhere. In many countries it’s only offered once or twice per year. Even here in the U.S., it’s offered only nine times per year.

Then there’s test itself.

"The LSAT is unique in that it is really a wholly skills-based test," says Glen Stohr, an LSAT test prep instructor with Kaplan. "It is logic, reading and reasoning that you're applying to the questions."

And those skills are not as familiar to the average college grad as the skills tested on the GRE. For example, there's a section known in the legal world as logic games — complex word problems that test analytical reasoning.

According to Stohr, this part strikes the most fear in the students he works with. The good news, he adds, is everyone can learn these skills. "And by practicing them, they can improve their logic games performance enormously," he says.

But getting that practice and the right tools to help you perform competitively can be expensive. Most LSAT prep classes today can cost around $1,000 and tutors are even more expensive. Factors like that can make applying to law school feel out of reach for a lot of people.

After three years, Dean Miller at the University of Arizona says the GRE policy seems to be working.

"We had demand right from the beginning," says Miller. In 2016, the first year of the program, he says the law school received 35 applications with a GRE score and matriculated 12 students. In 2018, those numbers grew to 70 applications and 18 matriculations.

"They have been distributed throughout our class and have achieved all of the successes of others," adds Miller. "The employers have also not distinguished between the LSAT and GRE admits."

According to Miller, students who were admitted using the GRE tended to be older and were more likely to have had a previous career, like recent graduate Christina Rinnert, a 52-year-old single mom who had been working in the nonprofit sector until 2016.

"It was the plan to come to law school. Then life got in the way," she says, adding the time and expense involved with studying for the LSAT was always a non-starter.

"To be quite honest I had put law school out of my head. I thought it was out of reach for me," says Rinnert.

But when she heard about the new GRE policy at the University of Arizona, she jumped at the chance. She successfully graduated from the program this spring.

Officials at Harvard Law School are reporting similar results.

According to the admissions office, in the two years the school has been running the pilot program, applicants who submitted only the GRE were more likely to be international, more likely to have significant work experience, and more likely to be from an under-represented racial minority or ethnic group.

"It seems to be working for us," says Jobson, the assistant admissions dean.

Changes For The LSAT

But the makers of the LSAT, the Law School Admissions Council, push back on the criticism that the test can feel inaccessible to some people.

Lily Knezevich, the organization’s senior vice president for learning and assessment, points to the LSAT’s origin story. When it was created in the 1940s, it was meant to be an equalizer.

"The legal educators at the time wanted to open access to anyone who could do the work," says Knezevich, "to get away from the old boys network where what school you went to as [an undergraduate] student determines what your law school opportunities were."

But as times change, Knezevich adds, the council is looking to adapt.

On Monday, for the first time, the LSAC will administer the test on a tablet to half of its test takers to begin a transition to digital testing. The organization recently increased the number days the test is offered from four to nine. And Knezevich points to the fact that the council also launched a new partnership with the Khan Academy, an education nonprofit, to provide free online test prep classes.

Critics of standardized testing say law schools should go further and ditch the test requirement altogether. But law school accreditors say making that leap is tough. Law school is expensive, they say, and admissions officers need some way to predict if a student will succeed.

This segment aired on July 15, 2019.