Advertisement

How Massachusetts Lost Count Of Its Poor Students

Resume

Massachusetts lawmakers are working this summer to overhaul the state’s approach to financing public schools with a particular goal of targeting more resources at the state’s lowest-income students.

But there’s a problem: Lawmakers don’t know just how many low-income students there are in the state or where they go to school.

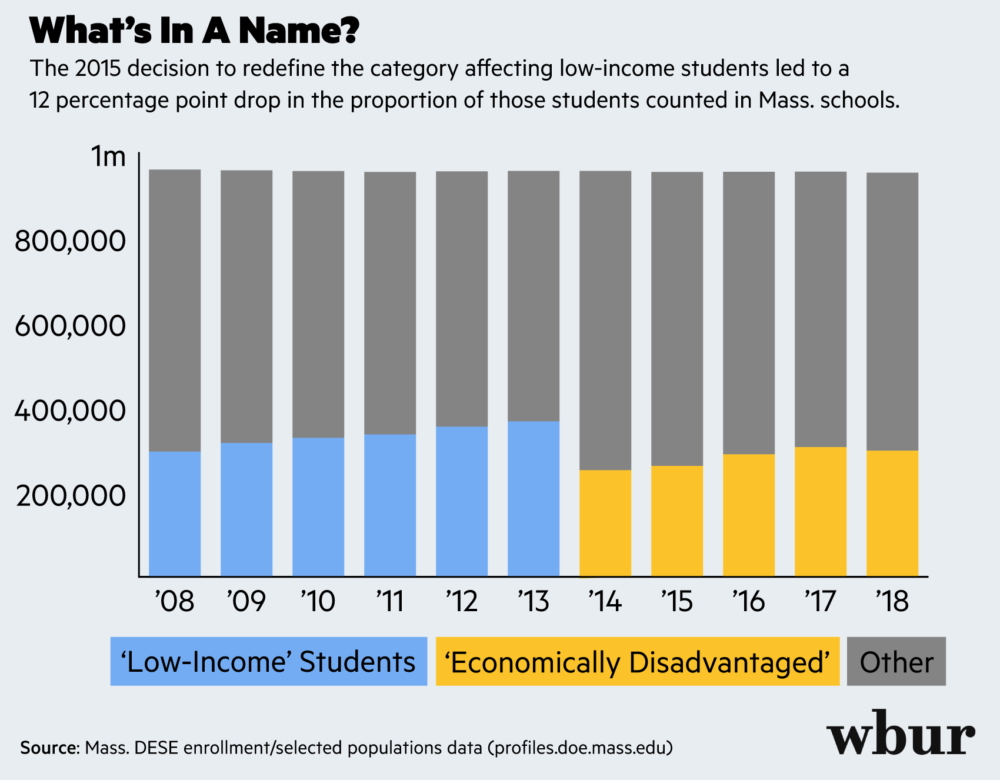

The trouble began in 2014, when officials at the state's Department of Elementary and Secondary Education began to introduce a new metric regarding students in poverty called “economic disadvantage.” The new definition was automatically applied to students enrolled in state-run assistance programs like SNAP or MassHealth.

But activists and superintendents say the change had unintended consequences that set back the state’s neediest students.

First, it made almost a third of them statistically invisible. After the change went into effect, almost 115,000 low-income students vanished from state data.

Look too fast and the numbers can suggest a radical real-world decline in the problem of poverty in Massachusetts schools. But independent studies don't bear that out.

Ed Moscovitch, the researcher who designed the state’s 25-year-old funding formula, described the relabeling as “a disaster, from a research point of view.”

“It destroyed the statistical basis for sorting out what teachers do [versus] the impact of where the kids were when they came” to school, Moscovitch said. And in a system still singularly focused on standardized testing, he argued, that matters: How can the state determine what’s working to improve low-income students’ performance if it can’t locate and track those students?

But the fallout wasn’t limited to data. The change distorted the state's picture of who is struggling financially in Massachusetts classrooms, and troubled its efforts to help them.

Good Intentions

Dianne Kelly, the superintendent of schools in Revere, said her district still hasn’t recovered from the change. But she noted that it started out as part of something “well-intentioned."

In 2011, as part of the push (led by Michelle Obama) for better nutrition for young students, the U.S. Department of Agriculture launched the Community Eligibility Program, or CEP, to expand the federal program offering free and reduced lunch.

The federal government's original free school lunch program dates to the Truman administration, and covered more than 5 billion meals a year in 2011. But it required millions of families to submit paperwork to confirm that their incomes were close enough to the poverty line to qualify.

CEP changed that. Starting in 2011, if at least 40% of students in a district or school were enrolled in government assistance programs, the federal government would allow them free or reduced lunch to all students, then reimburse them for part of the cost. (Given the reimbursement mechanism, the program only became valuable in districts where the percentage was higher: around 60% or greater.)

A 2016 guide to CEP listed its potential benefits. The program would automatically enroll needy students based on existing data. It would end “the peer-group stigma sometimes associated with free or reduced price status.” And it would cut down on paperwork both for families and for districts, "easing the administrative burden.”

(The paperwork was no small thing. A Brockton official described a dozen district employees working overtime to process thousands of income-disclosure forms in a single month.)

In Boston Public Schools, city officials saw CEP as a “win-win.” Former Boston Mayor Thomas Menino said the city “jumped at the chance” to join the program as a pilot district in 2013, when 77% of its students were classified as “low income."

Menino praised the program for taking “the burden of proof off our low-income families,” which it did. Starting the following year, Massachusetts’ Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) actively encouraged all eligible districts to take part in CEP as it was rolled out, and let income reporting fall away.

But Moscovitch said that from the beginning, he and others saw potential downsides. The program involved giving away the clearest map of poverty in state schools, which was based on families’ annual paperwork. (Other states did both: California accepted CEP into schools, but continued to collect income information every four years and from new students.)

Moscovitch's hesitation came from how the policy change would affect immigrant families. Most legal immigrants are barred from using benefits like SNAP for their first five years in the United States.

Any administrative savings, Moscovitch said, came at a high price: “We adopted a definition of poverty that effectively required, with one small exception, that you be a legal resident of the country for at least five years. … How do you defend that?”

And Mary Bourque, superintendent of Chelsea Public Schools, said that many undocumented immigrants might enroll in MassHealth Limited on a temporary basis — thereby turning up in state databases — but then choose not to renew it for fear of attracting attention that could lead to deportation.

"Many of them are afraid," Bourque said. "And so naturally what ends up happening is our students fall off the rolls. It's reflective of the times we live in."

Missing Students

The redefinition ended up skewing the picture of who attends school in Massachusetts to considerable effect.

For instance, last year, state data show 58.3% of Boston students as “economically disadvantaged.” But district officials said their own internal reporting said the actual number was 66%, suggesting the state didn’t count approximately 4,000 students in need of extra resources.

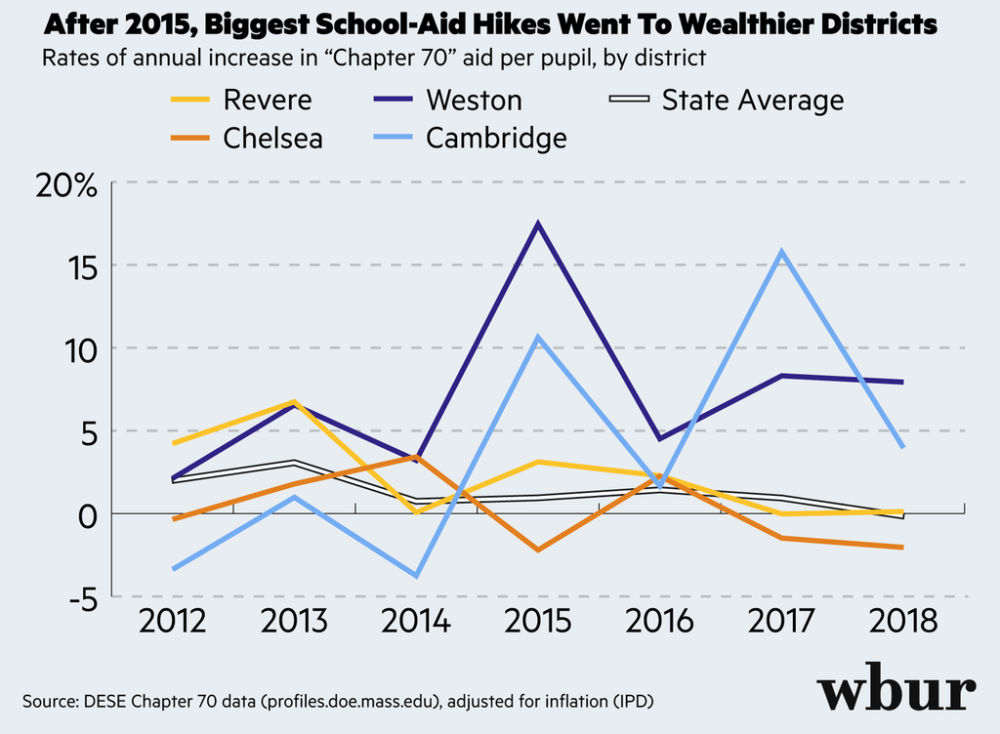

And since districts get an aid "increment" for each “economically disadvantaged” student they enroll — at least $3,755 under the latest budget — the change inevitably led to declining aid in districts with high concentrations of low-income immigrants or unenrolled families.

In Revere, an enrollment that was 77.8% "low income" turned over the summer of 2014 into one that was 37.4% "economically disadvantaged."

As the new demography was reflected in aid payments, state aid to Revere effectively flat-lined for two years (after adjusting for inflation and on a per-pupil basis). “It was really difficult for us,” said Kelly. “We didn’t have to have any layoffs, but we had over 20 staff positions that we just didn’t fill — and that meant our class size went up.”

Revere’s average class size has increased slightly of late — from 19.7 students in 2012 to 20.2 last year — while the state average hovered close to 18 over the same period. But Kelly said some teachers have confronted classrooms of around 30 students for the past four years.

And while the category change that came in after CEP may have lightened the administrative load in some districts, it added to the burden in Revere.

Kelly hired a full-time member of staff whose job was to inform families about programs that would get them certified as "disadvantaged," and "lets them know why it's important, both for the family and for the school district, if they do so." By last year, the share of Revere’s students bearing that label had climbed from 37% to around 47%. But that’s still lower than the real number, Kelly said, and the increase took “an enormous amount of work and energy.”

Even as the new metric was rolled out, policymakers at DESE recognized there could be a “differential impact” in its implementation, and they responded by sending some supplemental aid to the districts that would be hit hardest.

DESE officials did not speak on the record for this story, but in a statement, spokesperson Jackie Reis said that districts like Revere ended up with "significant increases in state aid" after the change, adding that "no measurement mechanism is perfect."

That supplemental aid made up the gap in Revere so that in terms of raw dollars, they saw aid increase over the period in question. But all in all, officials from the hardest-hit districts, including Brockton and Chelsea, said that they wound up effectively level-funded in the years after the change, even as costs rose, resulting in layoffs.

In response to the change, the state also increased the "increment" it sent to districts for each "disadvantaged" student beginning in the 2017 fiscal year. In a review of the policy, DESE officials wrote that "for the overwhelming majority of districts, the higher rates fully compensated for the lower student numbers."

But it also sent more money to relatively wealthy districts. Weston, Nantucket, Concord and Cambridge — each with a relatively small minority of low-income students — all saw their per-pupil Chapter 70 aid increase by 39% or more between 2014 and this year.

What's Next

DESE policymakers did acknowledge that the change had its flaws.

That 2017 review noted that since “refugees and undocumented immigrants are disproportionately under-counted” and concentrated in a handful of districts, and it conceded that “it is reasonable to assume that [the new metric] creates some systemic bias.”

And in her statement, Reis added that the districts that were set back will likely benefit from a forthcoming bill that would rework the state's education finance system.

Affected staff have their own ideas about how to restore the clarity that existed before the change. In Revere, Kelly proposes borrowing a solution from the federal government, multiplying the lower state count by some factor to reflect those students have gone missing. And Moscovitch said Massachusetts could do what California did — namely, go back to collecting free and reduced lunch applications on a less frequent basis.

The lawmakers working on a bill to reconfigure school financing in Massachusetts are eager to make a change on this score — though they're loath to talk about what it might be as a deal takes shape.

Sen. Jason Lewis, co-chair of the Legislature's Joint Committee on Education with Rep. Alice Peisch, is leading the negotiations.

Lewis also echoed Reis in saying that after a broad review, he and others have found that "there's no perfect solution" when it comes to capturing the prevalence of poverty in schools. But he also conceded that the status quo "is not equitable — schools that serve large numbers of poor students, immigrants, students of color have far fewer resources."

Lewis was mum about how the bill — which lawmakers hope is set to arrive before the end of this year — might end the under-counting of poor students, except to say "we have some good ideas."

But Lewis, who represents Malden, another district that lost out in the change, was emphatic on one point regarding the under-count: "Any education funding reform bill needs to address it, once and for all."

This segment aired on August 1, 2019.