Advertisement

How 'Rock's Greatest Manager' Shaped Led Zeppelin's Success

Resume

Guitarist Jimmy Page was the musical genius behind Led Zeppelin, one of the most legendary bands in rock music history. But the group also had a genius of sorts as its manager. His name was Peter Grant, and a great deal of Led Zeppelin's success can be traced to him.

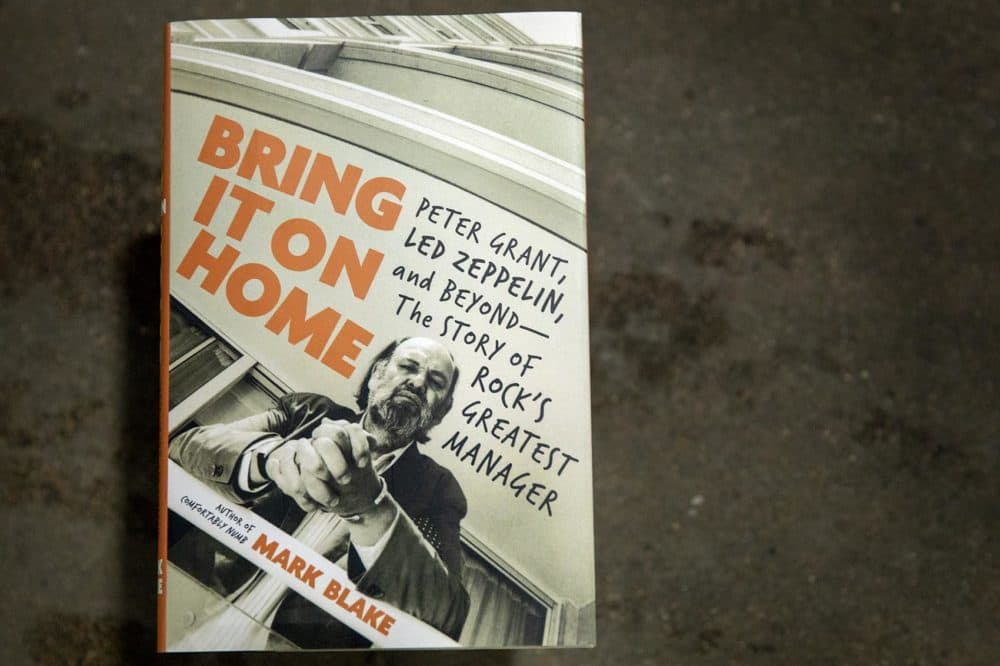

In his new book, author Mark Blake (@markblake3), "Bring It On Home: Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin, and Beyond —The Story of Rock's Greatest Manager," looks at Grant's life and impact.

Grant revolutionized what it meant to be the manager of a rock 'n roll band, Blake tells Here & Now's Alex Ashlock. He did something that was unheard of at the time: He didn't put Led Zeppelin on television, and the band didn't release any singles. If you wanted to hear them, you had to buy an album or go to a show.

"What Peter was fantastic at doing was being the enabler. If Jimmy [Page] said he wanted to do something, Peter would do it unquestioningly," Blake says. "He understood show business, and I think that included understanding the mystique of Led Zeppelin, creating an aura around them."

Interview Highlights

On Grant's beginnings in the music industry

"Peter's whole music business career began and was played out ... at the Cumberland Hotel in Marylebone, which is where he first witnessed a smashed-up hotel room. That was Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, had a row over a woman, and Gene Vincent tore the door off Eddie Cochran's hotel suite. First time Peter had ever seen anything like that. Manager phoned him, and he was absolutely outraged. He said to them, 'We don't do things like that in Britain. You're in the United Kingdom now. We do not do that sort of thing.' Fast forward five years, and he's got [Led Zeppelin drummer] John Bonham smashing up a hotel suite with a billy club in America."

"I think what Peter had seen was that the music was going to go somewhere beyond two-and-a-half, three-minute pop singles."

Mark Blake

On Grant's early career as a theater stagehand

"He learned how to do this at a place called the Croydon Empire, which was ... what is called in America a vaudeville theater, and that's what he was doing, looking at magicians, showgirls, balancing acts, ventriloquists ... guys with spinning plates. ... He later put a plate spinner on the same bill as Led Zeppelin in 1975. And that's where he learned about old-school show business. And from there, he started driving acts around — comedians, magicians, the same sort of artists — and then eventually, they're visiting American rock 'n roll groups that came to U.K. — Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent, Little Richard — Peter ended up being their driver and road manager."

On managing Jimmy Page and The Yardbirds

"I think what Peter had seen was that the music was going to go somewhere beyond two-and-a-half, three-minute pop singles, and a lot of what The Yardbirds were doing on stage in 1967, '68 was very very close to what Led Zeppelin ended up doing. I mean, they were already doing versions of songs like 'Dazed and Confused.' "

On Led Zeppelin's overnight success

"The whole thing was that everything happened very very quickly, but it happened in America. Peter took them to America very very early on, and they were opening for other groups — Iron Butterfly, Vanilla Fudge — and basically blowing them off stage. It happened remarkably quickly, and they spent most of 1969 touring America. They'd come back for a few weeks and then go back again, playing these kind of opinion-making clubs all across the country. And when the album came out, the first Zeppelin album, it just absolutely blew up for them. So it happened incredibly quickly, but it happened in America first.

"But that also helped build the mystique. Suddenly, they're this British band, this mysterious British band, that had gone to America to find their fame and fortune. Also they didn't release singles, and they did not appear on TV, and that was such a revolutionary move at the time. People thought it was career suicide, but again, this added to the mystique. You wanted to listen to the music, you had to buy a long-playing record. If you wanted to see them, you had to buy a concert ticket. You wouldn't see them on TV. And that was unheard of at the time."

"They all got slightly drunk on their own power. And as a result of that, there was an air, a real tangible air of menace around Led Zeppelin, around Peter."

Mark Blake

On how Grant always put the band first and the darker side of success

"When the money really starts to come in, which is around about '72 to '73, by which time Led Zeppelin can get 90 percent of the gate, which is unheard of for any artist. It was normally 60-40 towards the artist. Peter demanded on 90-10, rode out promoters, and obviously made an enormous amount of money for himself and the band. But with that came problems in his marriage, the excessive touring that was going on, plus cocaine had come into the mix certainly by the early '70s, and Peter succumbed to that as well. And I think in a way, the band, or certainly Peter and possibly Jimmy Page, they all got slightly drunk on their own power. And as a result of that, there was an air, a real tangible air of menace around Led Zeppelin, around Peter. You talk to people that toured with them and knew them at the time, they were terrified of Peter and his entourage. And I think again that was something that worked to their advantage, but it brought a dark side, it cast a shadow, I think, over all this success."

On drummer John Bonham's death and Grant's later years

"He never really recovered from that. He did dabble in management. But he spent a lot of time in the 1980s — he was with his kids, he was accessible to children — but he spent a lot of time in the 1980s barricaded away in his moted 15th-century mansion in the English countryside ignoring everybody, ignoring phone calls. He was being looked after by various gophers and minders, some of whom perhaps didn't have his best interests at heart. He still made an enormous amount of money, but he was not really doing very much. And I think there was a tragic side to it. I think what redeems the Peter Grant story is that before he died, some years before he died, he got himself back on track again. And he did that by turning his back completely on the music business and just concentrating on being a family man, stopped drinking, stopped taking drugs and lost an enormous amount of weight as well. And that's how he spent the last few years, and I think that's the redeeming part of the story. But there is a tragedy, definitely."

Alex Ashlock produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

Editor's Note: The book excerpt below contains some explicit language.

Book Excerpt: 'Bring It On Home'

“They were both rather sweet,” remembers Cole, who had Christmas dinner with a girlfriend in Laurel Canyon, leaving Bonham and Plant to fend for themselves. By the end of the day, a delegation of LA’s beautiful people, its scenesters, and Sunset Strip party girls had found their way to the Chateau Marmont to meet what Atlantic Records was calling “the hot new English group.”

John Paul Jones arrived in time for Zeppelin’s first American gig—an unbilled slot at the Denver Auditorium, opening for heavy psychedelic rockers Vanilla Fudge. Promoter Barry Fey had to be persuaded to put them on the bill. It didn’t hurt that Zeppelin and Vanilla Fudge shared the same lawyer.

“I’d love to say it was a life-changing event, but it wasn’t,” says Carmine Appice. “Robert Plant stood very still on stage. I remember saying to him later, ‘You should move a bit more.’ But you could tell there was something there.”

It would only get better, and quickly. “You could tell by the fourth night, in Portland,” says Cole. “I’d never heard anything like the drummer, and I suddenly thought, ‘OK, this is going to be enormous.’” Cole had spent the past year hopping between bands and tours. “And I’d had enough. As soon as Peter turned up, I asked for a full-time job with Zeppelin. And that was it from then onward.”

Grant arrived in time for January’s four-night stand at San Francisco’s Fillmore West, the nexus of the West Coast’s underground scene: “I said to the band, if you don’t crack San Francisco, you can go home.” Zeppelin opened for local heroes Country Joe and the Fish, but the headliners’ ramshackle folk-rock couldn’t withstand the assault.

The message was driven home when Zeppelin’s self-titled debut arrived at the end of the Fillmore run. The cover, which so upset Countess Eva Von Zeppelin, showed an eerie monochrome image of the Hindenburg airship going down in flames. The picture matched the music.

Songs such as “Dazed and Confused,” “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” and “Communication Breakdown” were a masterclass in drama and dynamics. There were few restrictions, and Page encouraged every band member to show their true musical personality. For Bonham, whose drumming was considered too forceful by some, the freedom was unprecedented.

Atlantic had distributed a few hundred white-label copies to key DJs and writers, and by the end of the tour the album had cracked the Billboard top ten and sold five hundred thousand copies. It would go Gold by the summer.

Two weeks after San Francisco, Led Zeppelin played for four hours at the Boston Tea Party, bumping up their set with Beatles and Who covers, after the audience wouldn’t let them leave. It was a pivotal moment when everybody, including Grant, realized they’d made a breakthrough.

“Peter was absolutely ecstatic,” remembered John Paul Jones. “He was crying—if you can imagine that—and hugging us all. You know, with this huge grizzly bear hug. I suppose it was then we realized just what Led Zeppelin was going to become.”

By the time they reached the East Coast at the end of January, Grant could start making demands. Peter and the Fillmore manager Bill Graham would fall out badly in the late seventies. In 1969, the relationship was cordial, if cautious. “Bill didn’t like the Yardbirds,” claimed Grant, “because Jeff Beck kept walking out.” Graham agreed to put this latest version on at his new New York venue, the Fillmore East.

Zeppelin were booked to open for Iron Butterfly, an American group, which, like Vanilla Fudge, played what critics were calling “heavy rock.” The same description was soon being used for Led Zeppelin.

Grant approached the Fillmore East dates like a wrestler preparing for a championship brawl: “I knew they could nail Iron Butterfly’s arse well and truly into the ground. So, I said to Bill, ‘We’re not going to open.’”

It was a remarkable display of bravado. Graham did as he was asked and booked another act—country-blues duo Delaney & Bonnie—putting Zeppelin second on the bill. And still the headliners ran scared. “When Iron Butterfly’s management found out, they wanted Zeppelin off the bill,” Grant said. “They didn’t want us near them.”

“Peter was so committed to what we did,” Plant told me. “His tough guy image came out of there being so many cowboys around and the way musicians were taken advantage of. Peter just bluffed everybody out.”

Grant relished the competition, believing headline acts were there to be toppled. But while he’d never forget the victories, he could never forgive the slights. Weeks later, Rolling Stone, America’s new taste-making music magazine, gave Zeppelin’s debut a critical mauling, with writer John Mendelssohn suggesting it “offers little its twin, the Jeff Beck Group, didn’t say as well or better three months ago.”

That particular comment stung. Grant had played Jeff Beck an acetate of the Zeppelin album, unaware it contained a cover of the blues song “You Shook Me,” a track also featured on Truth. “I thought, ‘Oh, this is a great tribute to us. OK, now where’s the album?’” Beck recalled. “And Peter said, ‘This is the fucking album; you’re listening to it.’”

Jimmy Page insisted he’d never heard Truth until after Zeppelin had recorded its album: “It was a total freak accident.” However, it didn’t help that John Paul Jones had played on Beck’s version as a session musician, or that Grant would tell anyone who listened that he, rather than Mickie Most, had produced Truth.

“When Truth was finished, I sent Jimmy a white-label copy,” said Grant. “Some time later Jimmy asked me why I hadn’t told him that Jeff had done “You Shook Me.” This was after Led Zeppelin’s version had been recorded. I told him about the white label, and he hadn’t even gotten around to hearing it.” If it seemed like an oversight on Grant’s part, there was another plausible excuse. He hadn’t noticed. “Truth was the only album I produced,” Grant admitted. “I’m not a musician, and I don’t profess to know much about music.”

The comparisons between the two albums were inevitable. Page and Beck shared the same influences, but as bands, Led Zeppelin and the Jeff Beck Group were very different beasts. Grant and Page had already generated an “us-versus-them” attitude toward the outside world. There was no such spirit in Beck’s group.

Furthermore, while Peter Grant sold himself as the artists’ champion, he still observed a pecking order. However much Grant defended Rod Stewart, the feeling wasn’t mutual. “Jeff was well looked after, and the band was totally ignored,” complained Stewart. “I remember [Ron Wood] Woody and I having to scrounge around Peter and Mickie Most’s office to see an accountant, who would make us wait five or six hours to get paid.”

Beck was a gifted musician, but by his own admission he wasn’t a band leader like Jimmy Page. He was also envious of Led Zeppelin’s rhythm section. In February, Beck asked Grant to fire Ron Wood and Mickey Waller.

Richard Cole, their then road manager, remembers the call. “They got in this Australian bass player who did the gig in bare feet,” he recalls. “He was terrible, and they had to get Ronnie back. Of course, he said ‘Fuck you. I want twice as much money.’”

“I loved hearing Peter Grant squirm,” admitted Wood, who insists Grant also offered him a job with the New Yardbirds. “I said, ‘I’m not joining this fucking bunch of farmers.’ And they became Led Zeppelin. Not my scene at all.”

Excerpted from "Bring It On Home: Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin, and Beyond—The Story of Rock’s Greatest Manager by Peter Grant." Copyright © 2018. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

This segment aired on November 26, 2018.