Advertisement

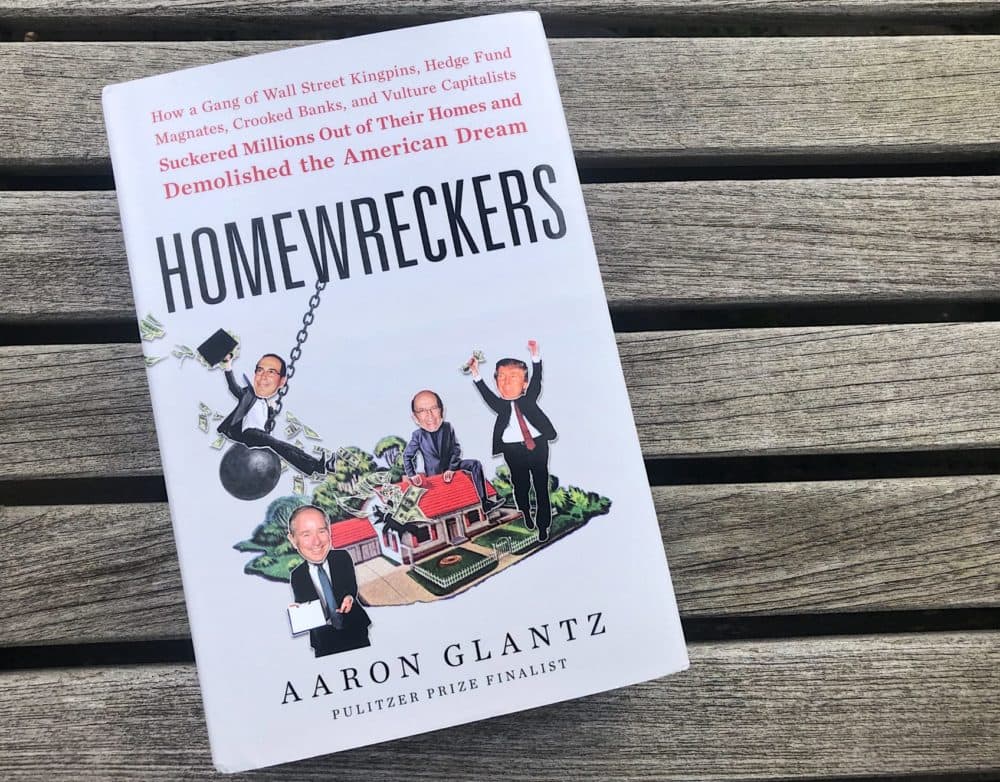

'Homewreckers' Book Probes How The 2008 Housing Crisis Killed The White Picket Fence American Dream

Resume

Host Tonya Mosley speaks with author Aaron Glantz about his new book, "Homewreckers: How a Gang of Wall Street Kingpins, Hedge Fund Magnates, Crooked Banks, and Vulture Capitalists Suckered Millions Out of Their Homes and Demolished the American Dream," which explains how some well-placed financiers took advantage of the 2008 housing crisis to buy thousands of family homes.

Book Excerpt: "Homewreckers"

By Aaron Glantz

Most of the beneficiaries of the foreclosure crisis were not first-time home buyers who secured a thirty-year fixed mortgage with family support. Instead, they were a new breed of corporate landlord that bought up entire neighborhoods and held the homes in shell companies, with the true identities of their owner unknown to most of the new tenants. In Oakland, for example, a nonprofit organization called the Urban Strategies Council found that between January 2007 and October 2011, more than 40 percent of the 10,508 homes that went into foreclosure in the hard-hit city had been purchased by real estate investors—usually with cash.

After Bank of America took Theodros Shawl’s bungalow, it sold it to a shell company called REO Homes 2 LLC, which purchased 171 foreclosures in Oakland after the bust. The sale price? Just half the balance Shawl was seeking in mediation: $152,000.

Two months later, the company put the home back on the market as a rental, describing it as a “gorgeous remodeled Craftsman-style house” with a converted basement, a large deck, and a backyard. This turn of events confounded economic expectations. Rents were already high. On paper, at least, all the economic incentives favored homeownership. For example, Shawl’s old home was listed for a daunting $2,595 a month—a price that would allow the new, corporate owner to repay the entire cost of the purchase in less than five years. Most of the other homes in the limited liability company’s portfolio were being rented out at similarly high prices. Public records showed that, on average, the company paid $139,000 per home—meaning that if families had bought these houses with traditional thirty-year mortgages, they would have ended up paying about $600 a month, not counting taxes and insurance. By buying at the bottom, they—like me—would also have insulated themselves from rising rents, keeping down costs as the economy recovered. With each monthly payment, they would have been paying down the principal, building equity, and generating wealth to pass on to the next generation. Instead, all that wealth would go to the shell company’s investors.

The rise of these corporate landlords drove a generational transfer of wealth from hundreds of thousands of individual homeowners to a handful of well-heeled bankers and titans of private equity. But wasn’t this just the way of the market? If someone wanted to buy one of those $139,000 homes, he or she just needed to get there first, before REO Homes or whichever LLC was trying to scoop up the local housing stock. The problem was that the system was rigged in favor of the speculators. In fact, as the years passed and the economy recovered and jobs returned, banks still refused to lend to individuals and families, and the nation’s homeownership rate continued to fall, until, in 2016, eight years after the crash, it hit its lowest level in more than fifty years. Like the wave of foreclosures themselves, this credit desert particularly harmed people of color, with the homeownership gap between blacks and whites opening wider than it was during the Jim Crow era, when discrimination was legal and encouraged by the government.

These developments had sweeping implications. In America, the average homeowner boasts a net worth that is a hundred times greater than that of a renter: $200,000 for homeowners compared with $2,000 for renters, according to the US Census Bureau.

This is not because homeowners make a hundred times more money than renters. (Homeowners take home about twice as much every month, according to the government.) Rather, it is because owning a home represents the only way for most middle-class families to save money. Researchers at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution found the average middle-class household spends nearly 80 percent of its income on just five essentials: housing, food, clothing, health care, and transportation. In other words, most of a family’s money is gone before they can even think about going to the movies or sending their children to college. The news gives us daily updates on the Dow Jones Industrial Average, but figures from the US Census Bureau tell us this is largely irrelevant to most Americans’ savings plans. Indeed, only 20 percent of American families own stocks or mutual funds, and the average household has about $4,000 in the bank.

So, month after month, most of a family’s income disappears. Clothing is worn until it is discarded. Food is eaten. Health care dollars disappear into the accounts of insurance companies and hospital chains. Gas money is burned up by a car that, if purchased, loses value the moment it is driven off the lot. Only housing, representing 35 cents of every dollar spent by the average middle-income family, has the chance to retain, or even increase, in value. Every month, when a homeowner makes a mortgage payment, she basically makes two payments. The first is a tax-deductible check to the bank that covers the interest, and the other is to herself, in the form of additional equity in her home.

By buying up large numbers of homes during the bust, real estate magnates removed properties from the market and stole this opportunity from millions of Americans. These speculators were part of a great but inglorious US tradition. In every generation, there are people who hold their money, waiting for a crisis, so they can pounce and profit off the pain of others, often creating financial dynasties that last generations. Their organized disaster profiteering has been with us since at least the Civil War. The Panic of 1873, a multiyear economic collapse spawned by inflation and rampant speculation by railroad tycoons, allowed John D. Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Company, to buy out his competitors and corner the oil market, while industrialists Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Carnegie gobbled up large sections of Pittsburgh and its nearby mining assets and launched US Steel. President John F. Kennedy’s father, Joseph Kennedy, famously shorted the stocks of America’s largest corporations after the 1929 stock market crash and then used the Great Depression to amass an empire’s worth of real estate, liquor companies, and movie studios.

The very phrase “American Dream” comes from this dark period, coined in 1931 by Pulitzer Prize–winning historian James Truslow Adams in an immodestly titled book, The Epic of America. An early selection of the Book of the Month club, it was a runaway best seller. What made the country unique, Adams argued, was opportunity. America, he proclaimed, was not like the Old World of Europe, where vast sums of wealth passed from kings, queens, and lords as a result of their noble birth. It was a place where success was based on hard work. “The American dream,” he wrote, is a “dream of being able to grow to the fullest development as a man or woman, unhampered by barriers which had slowly been erected in older civilizations, presented by social orders which had developed for the benefit of classes rather than for the simple human being of any and every class.”

To some extent, that may seem like a call for unfettered capitalism and free markets, but Adams was a New Dealer who believed the government should intervene to make sure everyone had the chance to live the American Dream. “The project is discouraging today, but not hopeless,” he wrote, as leaders “are beginning to realize that, because a man is born with a particular knack for gathering in vast aggregates of money and power for himself, he may not on that account be the wisest leader to follow nor the best fitted to propound on a sane philosophy of life.”

This vision of the American Dream wasn’t against capitalism or moneymaking per se, but it was against amassing money simply for money’s sake. It was in favor of a certain type of moral capitalism, where people worked hard not only to make money but also to help their families and their communities. For Adams, the stakes in curtailing the power of gluttonous billionaires were high. Allowing them to effectively own the country would be “the failure of self-government, the failure of the common man to rise to full stature, the failure of all that the American Dream has held of hope and promise for mankind.”

From the book HOMEWRECKERS: How a Gang of Wall Street Kingpins, Hedge Fund Magnates, Crooked Banks, and Vulture Capitalists Suckered Millions Out of Their Homes and Demolished the American Dream by Aaron Glantz. Copyright © 2019 by Aaron Glantz. From Custom House, a line of books from William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

This segment aired on October 17, 2019.