Advertisement

For Guatemalan War Survivors, Arrest Of Accused War Criminal Is A Cause For Hope

Resume

Este reporte tambien está disponible en español.

In a cold, bare-bones apartment in a working class part of Providence, a woman in her mid-40s stirred a pot of hot chocolate. She said it was sent from Guatemala, “special for the cold.”

She poured the steaming chocolate into a mug on her kitchen table, where she keeps a black and white portrait of her father, Manuel Tzoc Ixcotoy. He’s one of some 200,000 people killed in Guatemala’s armed conflict, from 1960 to 1996.

“My father disappeared on July 12, 1982, and two years later my mother died of cancer,” she said in Spanish, glancing at times at her father’s face. “We were alone. We suffered hunger, pain, fear and insecurity ... we were just children.”

And the man she believes is responsible for her father's death, Juan Alecio Samayoa Cabrera, lives less than a mile from her home in Providence.

This woman -- and three other local Guatemalans related to people killed in the war -- spoke to WBUR on condition of anonymity. She fears allies of Samayoa could come after her children, here in the United States.

“My mother asked us before she died that our hearts never fill with anger against the people who took our father away,” she said. “I believe it was [Samayoa].”

Authorities in Guatemala say they are waiting for Samayoa with an arrest warrant in connection with crimes committed during the armed conflict.

Court records show the 67-year-old Samayoa is the father of eight, and had been living in Providence as an unauthorized immigrant since the 1990s. Providence police say he has no criminal record in the city, where he owns a triple-decker on Webster Avenue, and according to various accounts has worked as a landscaper.

In late October, officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested him for immigration violations -- a quarter century after he first came to the States illegally from Guatemala.

After Samayoa's arrest, WBUR made repeated attempts to interview him through his family and his lawyer. Samayoa and family members declined to comment.

While his deportation case proceeds, Samayoa is in ICE custody at the Bristol County House of Correction in Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

'You Are Very Famous' In Guatemala

The Providence woman said she found out by pure chance she was living in the same city as the man she thinks killed her father. Waiting in line at a Walgreen's pharmacy, she recognized Samayoa's face and black sombrero. Outside the store she confronted him.

“I told him he is very famous [in Guatemala]. Then I asked if he remembers Manuel Tzoc Ixcotoy and Diego Tzoc Ixcotoy," she said, referring to her father and uncle.

"He started to shake and his facial expression changed. … Then I got a lump in my throat, and I never saw him again.”

The Providence woman is an indigenous Mayan, part of a group that suffered what is widely seen as a genocide in the early 1980s. For some cold warriors of the time, it wasn’t about genocide, but a war against communism.

Many Guatemalans in New Bedford and Providence come from the Quiche region in the country’s western highlands. It was there that Samayoa, by his own admission, led a paramilitary unit of 500 men. The unit was part of Guatemala’s Patrulla de Autodefensa Civil, which was documented as carrying out scores of extrajudicial killings, including the murder of the Providence woman’s father and uncle.

The Guatemalan government provided WBUR with a court document containing allegations against Samayoa's alleged accomplice, Candido Noriega. In 1999, Noriega was convicted in Guatemala of six murders and two cases of manslaughter, and sentenced to 220 years. In the document, Samayoa is named alongside Noriega, accused of involvement in 38 murders and dozens of kidnappings among other crimes carried out in 1982 and 1983.

That was at the height of a genocide -- headed by President Efrain Rios Montt, who legalized the Patrulla de Autodefensa Civil -- that claimed the lives of well over 100,000 indigenous Maya. In Samayoa’s case, the accusations include burying people alive and torching their homes. The court document suggests one of the victims had his eyes ripped out of his head.

A man who recently moved to New Bedford from Guatemala says his father was killed in Quiche in 1982. The man, who also asked that his name not be used for fear of retaliation, said he remembers when Samayoa and his patrol came for his father.

“I know that man very well," he said in Spanish.

The New Bedford man said Samayoa's group left him alone but took his father away. He said he was later told that his father had been killed in a ravine.

“I remember it very well," he said. "[Samayoa] was heavily armed and he was wearing a black sombrero. He was bouncing around with his people like a madman. He knows very well what he did.”

Immigration Court

In mid-November, at a bail hearing in immigration court in Boston, Samayoa appeared via closed circuit TV from the Dartmouth jail. He was slouched and serious and looked like he'd just gotten out of bed. Ten Mayans came, some prepared to testify against him, but Samayoa's lawyer was not present and the hearing was continued.

A week and a half later, 20 of Samayoa's friends and relatives showed up to support him in court. Just a few Mayans were there. Samayoa's lawyer said he wants his client released while the deportation case proceeds.

But an attorney for ICE, Jennifer Mulcahy, argued Samayoa should not get bail because of “human rights violations in his own country,” filing a mammoth document to support the motion. It appeared to be the first time human rights allegations have been filed against Samayoa in an American court.

Samayoa's attorney received a continuance to study the filing, and the next date was set for mid-December.

After the hearing, Samayoa's wife and daughter declined to speak.

Asked if this is the first he's heard about human rights violations by Samayoa, his attorney, Hans Bremer, said, “I'm not going to comment about that, so, I'm sorry.”

'The Theater For Horrific Violence'

This is not Samayoa’s first time in immigration proceedings. In court documents filed in his asylum claim during the early 2000s, Samayoa detailed his version of how he got to the United States.

The records suggest Samayoa “made a good living” selling cattle and wood in Guatemala, “had several employees, owned land and a car, and had plenty of money."

“In the early 1980s, however, Guatemala’s civil war escalated; armed insurgents battling the government for power turned on the civilian population with a vengeance, raping and killing," reads one of Samayoa's filings. "And the region in which Mr. Samayoa lived — the Quiche — became the theater for horrific violence.”

Samayoa claimed he took up arms in self-defense, and in support of the military. In 1982 he began leading his local paramilitary unit in the municipality of Chinique, and he later joined the military as a recruiter of young cadets.

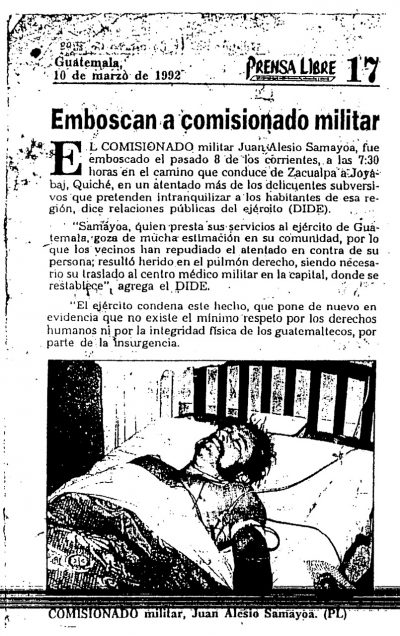

Without going into the details of his activities as a paramilitary leader, Samayoa claimed the guerrillas attacked him several times, and that he once spent three days in a coma.

After leaving the hospital, in 1992, Samayoa fled Guatemala and entered the U.S. illegally. His asylum claim was denied by the courts, and he stayed in Providence another 13 years before ICE arrested him in October.

People familiar with the case confirm ICE and the DOJ were investigating Samayoa going back at least three years.

“The fact that he's been allowed to live here doesn't surprise me,” said Kate Doyle, of the National Security Archives in Washington, D.C., who has testified in war crimes trials in Guatemala. “There are so many cases like Samayoa's that have not been uncovered and addressed.”

Doyle notes that Samayoa is one of more than 1,900 suspected human rights violators living in the U.S. And special units at the Department of Justice and ICE are going after them.

“I am confident that the ICE Human Rights Violators unit is looking at this case, as a way not simply to detain and deport an undocumented individual, but rather to highlight Samayoa as a human rights criminal,” Doyle said.

Justice In Guatemala

Guatemala’s top human rights prosecutor, Hilda Pineda, said officials there are waiting to arrest and charge Samayoa once he’s deported.

“I think he is a very bloodthirsty person with a great level of cruelty, given the way he killed people,” Pineda told WBUR in Spanish. “They were subjected to torture.”

Pineda said prosecutors want Samayoa to be sent to Guatemala, so they can do their job. “We want him to be sentenced based on the facts,” she said.

But some Guatemalans here in New England lack faith in the justice system in their country. Just a few years ago, the courts overturned a guilty verdict against perhaps the most notorious author of Guatemala's genocide: the octogenarian former President Efrain Rios Montt.

Advocates in the country, however, say things have changed.

They point to recent convictions of Guatemalan war criminals as evidence there will be justice for the victims of Juan Samayoa.

For Samayoa to make his way to a Guatemalan courtroom, ICE must first deport him, and that could take months, if not years.

With a picture of her father on her kitchen table, the Guatemalan woman in Providence is watching and waiting.

“This opens a new hope of knowing where my father is, to recover his bones and give him a Christian burial,” she said. “This is something you never forget. It marks you for life."

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified the municipality where Samayoa's paramilitary unit was based. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on December 13, 2017.

This segment aired on December 13, 2017.