Advertisement

This Centuries-Old Archaeological Site In N.H. Is Washing Away

Resume

Meghan Howey, a University of New Hampshire anthropological archaeologist, has a map. It was made in 1635 and it shows the location of garrison houses that once stood near Great Bay, in what is now Durham, New Hampshire. Garrison houses were a sort of fortified log cabin built by early colonial settlers in New England.

But Howey says even though we’ve had this map for almost 400 years, until recently, no one has actually gone out to find the sites, to look for what may have been left behind.

“It’s pretty shocking. The emphasis has been on the sites that would draw tourists," Howey says. "There’s a lot out there that’s just completely unknown.”

Howey leads me through the woods to a secret archaeological site in Durham, where last summer she found some of that unknown history. The site is secret, because it contains artifacts and human remains that can be a target for looters.

Howey and a team of volunteers discovered the location of one of the garrison houses on that map -- the remains of a structure where some of the earliest Europeans to ever be in this region lived, worked and died.

But that exciting discovery came with some sobering news.

We reach the end of the forest, where a steep bank drops to a narrow strip of sandy beach. Howey points to the ground beneath our feet.

I realize that she’s not showing me what’s here, so much as what’s gone. Most of the land where the garrison house once stood has been eaten away by the rising tidal water of the bay.

“Like quite literally washing away," says Howey, "and it’s gone, whatever the artifacts were with it -- they’ve been, over the years, just washed away.”

Just one corner of the garrison house's foundation remains on solid ground. A few feet away, Howey points out a couple of bricks submerged in the shallow salty water. She says the bricks were likely part of the garrison house's chimney and could date back to the 1600s. They are what remains of an archaeological site that's largely been lost.

“Yeah, it’s gone. It was a pretty depressing find," says Howey, before adding "it was a great find, but it’s a bummer. That’s how we felt last summer, like, ‘this is so cool and this is so sad.’ ”

“It’s only a matter of years before bodies probably come out of the bank."

Meghan Howey, UNH anthropological archaeologist

After Howey uncovered this site, she wondered how many others like it could be at risk of a similar fate — of being submerged in a rising sea, or carried away by stronger storm surges.

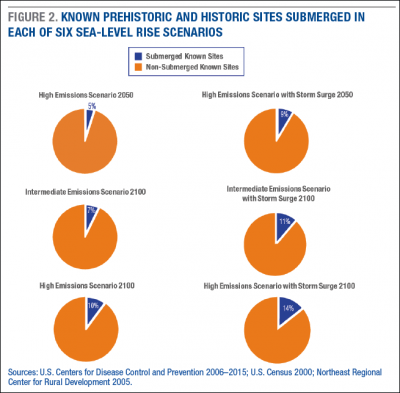

In a new report, she combined sea level rise projections from climate scientists with the location of historic sites on the Seacoast. She found that as many as 1 in 7 of the region’s known historic sites are at risk.

But even that number could be a low estimate because it doesn’t include sites like this one, which weren’t known until Howey found it just last year.

And it’s not only bricks that are being lost. Not far from the site of the garrison house, Howey shows me where the settlers who lived here buried their dead. It’s a cemetery containing some of the first Europeans to live in this area and every year the tidal waters inch closer.

“It’s only a matter of years before bodies probably come out of the bank,” says Howey.

In many cases, saving historic sites like this from climate change just isn’t feasible. So the best Howey can do is to document what’s here before it’s gone — an archaeological race against time.

“I feel a great sense of urgency, especially after finding these sites are washing away," says Howey. "There’s a part of me that feels I’m 20 years too late to the problem.”

This summer Howey is hoping to identify more garrison sites from that map she showed me. She says she wants to find as many as possible while she still can.

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative and was originally published by New Hampshire Public Radio.

This segment aired on April 23, 2018.