Advertisement

'Dancing With The Devil' Details Rio's Prep For 2016 Olympics

Resume

When Rio de Janeiro was voted host of the 2016 Summer Games, Brazilians celebrated as only Brazilians can. In Copenhagen, where the vote took place, soccer icon Pele and Brazil’s president Lula tearfully embraced. In Copacabana, fireworks, confetti and flags filled the air.

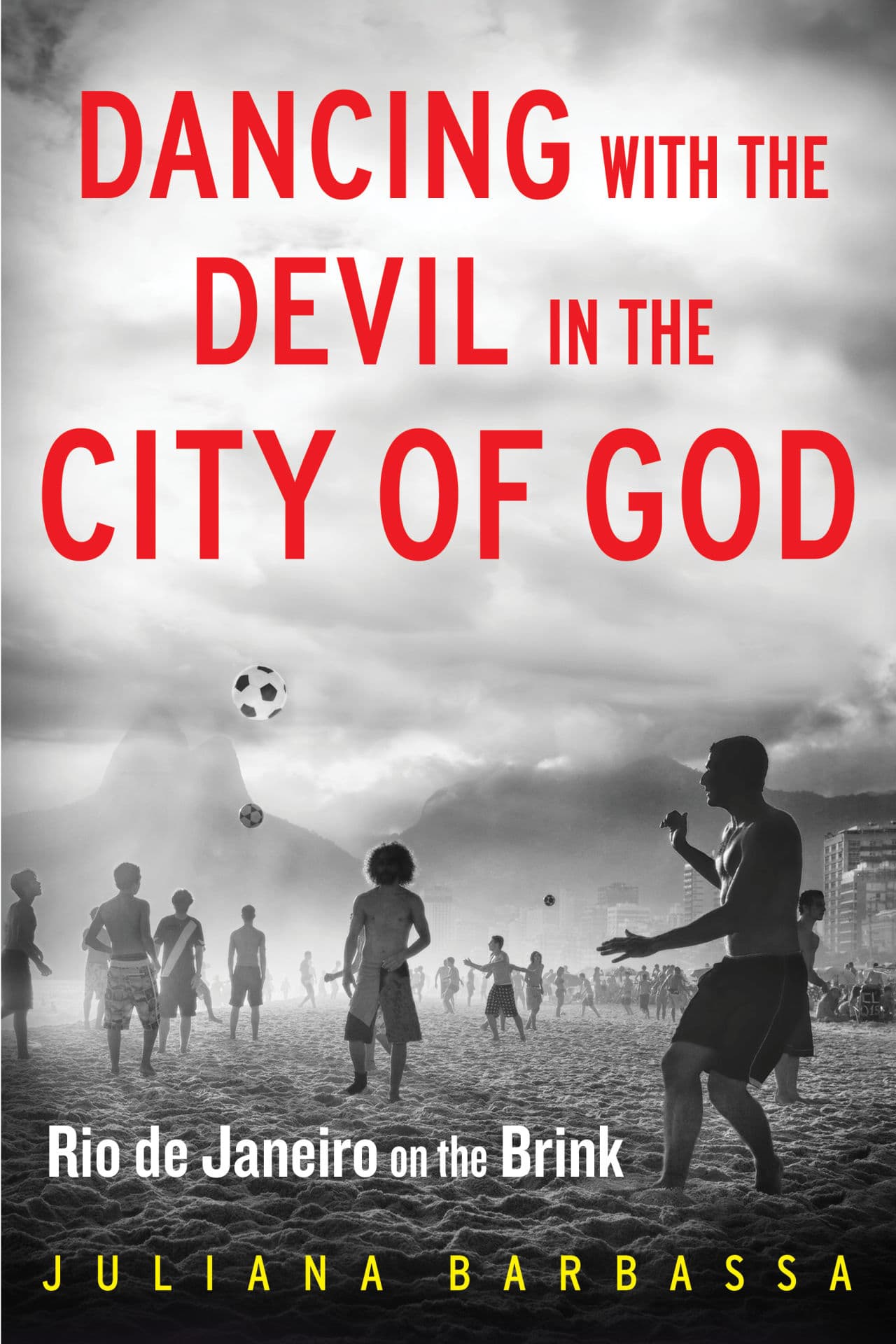

Those scenes pulled Brazilian journalist Juliana Barbassa back from abroad to her home city of Rio. She wanted to see how the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics would change the city and its people. In her new book, "Dancing with the Devil in the City of God," she chronicles that transformation.

Barbassa joined Only A Game guest host Shira Springer.

SS: When Rio was named host of next year’s Olympics, what did that signify for Brazil and the citizens of Rio?

JB: Well, it was going to be our time in the sun. Brazil was a country that had been in a military dictatorship until the mid-'80s and in the 1990s faced huge economic turmoil — hyperinflation, people couldn't plan their lives. Things finally started to change in the 2000s. By the time that Rio was chosen as the host city of the 2016 Games, there was this tremendous optimism — this sense that the country was booming, and the world had recognized that Brazil's moment to shine had come.

SS: But between the time when a city wins a bid and a city actually hosts a game, a lot can happen. It’s been six years since Rio successfully bid for the Summer Games. If the city bid today, how would Brazilians, especially Rio residents, feel?

JB: Well, very, very differently. Two big things have happened since then. One is that that economic effervescence that we were experiencing in 2009-10 has definitely taken a nosedive. The economy is stagnant. Inflation has reared its ugly head. Brazilians are a lot more ambivalent about big spending.

JB: Well, very, very differently. Two big things have happened since then. One is that that economic effervescence that we were experiencing in 2009-10 has definitely taken a nosedive. The economy is stagnant. Inflation has reared its ugly head. Brazilians are a lot more ambivalent about big spending.The other thing that happened is that Brazil first hosted the Pan Am Games back in 2007 and then hosted the World Cup in 2014. The Pan Am Games were more than eight times over budget, and they left us with venues that couldn't even be re-used for the Olympics. So we now have some experience in what it takes to hold these mega, international sporting events. We know what the costs are.

SS: And those costs aren't just financial costs. There's an opportunity cost that comes with hosting these mega events, right?

JB: The city's urban planning is taken hostage by these short-term events. And the goals of the World Cup or the goals of the Olympics become the city's goals. Less than two months after Rio was awarded the Olympics, the city published a list of 119 low-income communities, which in Rio are known as favelas, that would be demolished. The urgent need that we had for better housing, especially low-income housing, was not going to be addressed and, in fact, was going to be made worse. And in the process, one of the city's most entrenched problems, which is its inequality, was also going to be exacerbated.

SS: Describe the almost unbelievable scene that took place in Rio two weeks before the World Cup involving the Brazilian national team and striking teachers.

JB: In the year leading up to the World Cup, Brazilians really poured into the streets in protests that nobody had foreseen. And these protests, one little part of them included this group of teachers that were rallying near the airport, calling, like many people had, for less spending on stadiums and more spending on education. They had signs, they had stickers.

JB: In the year leading up to the World Cup, Brazilians really poured into the streets in protests that nobody had foreseen. And these protests, one little part of them included this group of teachers that were rallying near the airport, calling, like many people had, for less spending on stadiums and more spending on education. They had signs, they had stickers.And it happened that this protest of teachers crossed paths with the bus carrying the Brazilian national soccer team. Now these men are usually revered as demigods in Brazil and what happened was these teachers stopped the bus and started rocking them.

And the cops that were there raised their batons to the teachers, and you caught these pictures of the players inside the bus, some of them just looking in horror, some of them covering their faces in embarrassment. It was such a signifier of this big transformation in attitude that Brazilians had had.

SS: What do you expect to see from Brazilians in this year before the Olympics?

[sidebar title="An Excerpt From 'Dancing With The Devil'" width="630" align="right"]Read an excerpt from "Dancing with the Devil in the City of God" by Juliana Barbassa.[/sidebar]JB: There's no way of knowing what's going to happen now before the Olympics. The president's approval ratings are at a record low — less than 8 percent. The economy is stagnant. There's a widespread corruption scandal involving the big construction companies, so who knows how the Brazilians are going to process and digest all this in this year to come.

SS: Looking ahead to next summer, how do you think the Olympics will be received? What will the atmosphere be like in the iconic Maracanã Stadium for the opening ceremony?

JB: Well, I think that in spite of all this ambivalence, when it comes right down to the party, Brazilians will show up with their colors flying. Because that's what they do. I think it will be beautiful. I think the Games themselves will be beautiful. The real question is: at what cost?

This segment aired on July 25, 2015.