Advertisement

Poetry And Baseball: Revisiting 'Casey At The Bat'

Resume

This story originally aired on Feb. 27, 2016.

Say the words "baseball" and "poetry" to most people, and they’ll all smile and think about the same verse:

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine

that day:

The score stood four to two, with but one inning left to play.

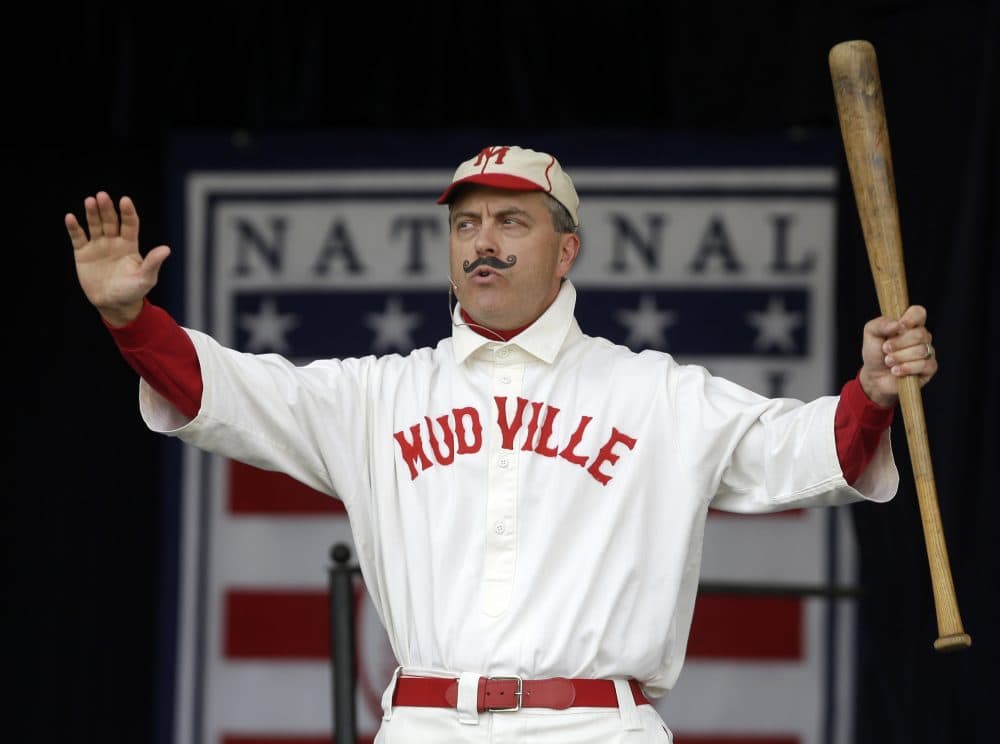

Yup. "Casey at the Bat," performed by DeWolf Hopper in 1909. No poem set in a game has achieved the notoriety of Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s doggerel, with which he tells the story of how the heroic Casey comes to the plate with the game on the line, lets two perfectly good strikes go by and then whiffs, rendering Mudville joyless. DeWolf Hopper, an accomplished thespian, read the melodramatic verse in packed theaters. Some members of the audience recited along with him. Others wept.

"Casey’s" charms have endured. He is the hero brought low. It’s a dependable theme. And there’s some suspense as the two batters preceding Casey, the hapless Flynn and even less promising Blake, both reach base. Then Casey lets two strikes go by, setting up the climax of the poem … though probably anyone should have been able to guess from the outset how that particular at-bat would turn out.

I mean, Mudville.

Casey plays for “the Mudville nine.” How likely is it that a team from a town called Mudville would prevail?

And then there’s age. On that memorable day he stepped to the plate, Casey’d been around for a while. How else would he have established such a reputation?

Then from 5,000 throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.

All of Mudville believed that if Casey could "get a whack," they would go home triumphant. They might even forget for a moment that they lived in Mudville.

Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance flashed in Casey’s eye, a sneer curled Casey’s lip.

So by the time the pathetic Flynn and undependable Blake reached base and Casey picked up the bat with which he intended to banish the gloom to which Mudvillians awoke each day, it felt heavy. His back probably hurt. Also his knees. In short, he was no longer the Casey of old; he was just old Casey.

Ernest Lawrence Thayer may not have been a great poet, but he understood the nature of myth well enough to know that it’s the fate of heroes to take on one-too-many dragons.

Mr. Thayer draws Casey’s flaw in capital letters. It’s pride. He’s over-confident. There is "ease" in his manner when he steps to the plate. There was no ease in the manner of Willie Mays when he stepped to the plate. And did Willie Mays ever sneer at the fellow on the mound? I think not. Casey’s lucky the pitcher didn’t start him off with a fastball in the ear.

Instead he gets strikes. Hittable pitches. But Casey opts for drama.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped –

"That ain’t my style," said Casey. "Strike one," the umpire said.

Casey waits until he has only one chance to lighten hearts in Mudville. By the time he exercises "Christian charity" toward the umpire by urging the fans not to go through with their murderous intentions against him, it’s too late. God is shaking his head, though probably not sneering. "What do you want?" He or She is saying. "I gave you two pitches to hit. Siddown, ya bum, ya."

It makes a terrible kind of sense, just as tragedy is meant to do.

And then the game ends, exactly when the poem does.

Mighty Casey has struck out.

Then, I imagine, Casey, baffled at his failure, probably slouches back toward the dugout. Maybe he’ll hang on for another summer or two, but his salary will be cut. One day as he’s chasing a fly ball, he’ll stumble like some old man tripped up by an uneven sidewalk. One fan in the near-empty bleachers will turn to another and say, "Geez, he should have quit a couple years ago." Soon enough, Casey will be hanging at the Mudville Tap Room, telling his story for beers, insisting that the third strike was a spitball.

Because "Casey at the Bat" is not tragedy. It’s pathos. And while it would be presumptuous to rewrite tragedy, that’s not necessarily the case here, which explains why lots of people have offered alternative endings to the story. It’s a temptation hard to resist.

The sneer is gone from Casey’s lip, his teeth are clenched in hate;

Alas, for what he might do next, it’s suddenly too late.

For Flynn, an absent-minded guy, a goofy sort of bird…

Has wandered from the base a bit and been picked off of third.

No? OK, how about…

Oh somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright.

But Mudville’s gloom ain’t permanent; folks there have got it right:

The fact that Casey let them down won’t really change a lot.

The Nine of Mudville? As a team, they’ve never been so hot,

And whether they have lost or won, as dark gives way to dawn…

The citizens of Mudville rise each day and soldier on.

As do the citizens of Pittsburgh, San Diego, Cincinnati, Kansas City and so on. Baseball’s in season again, and citizens have gathered in numbers to watch it, as they always do.

Casey struck out. So did Babe Ruth and Willie Mays. So do Miguel Cabrera and Bryce Harper, who'll get 'em next time, until there is no next time, at which point somebody else will get 'em. It’s the nature of the game.

This segment aired on April 29, 2017.