Advertisement

Gene Mingo: A Hall Of Fame Life

Resume

In at least one way, the defining moment of Gene Mingo’s football career — the one that led him from the Navy to the AFL and eventually to the NFL — happened in 1951, the summer before he turned 13. He spent that summer, like all the summers before it, hanging with his cousin, Dean.

"His name was Dean Newby, and we were inseparable," Gene says with a laugh. "Dean was much better looking than me, faster than me, smarter than me, tougher than me. I wanted to be like Dean."

Dean played football for the Akron, Ohio, junior bantam team, the Hornets. Before long, he convinced Gene to join him. And for the first week or so, it was good. Gene says he was proud to wear his uniform.

But then, "the coach called for a scrimmage," Gene says. "I don't forget if I was playing end or playing tackle. But anyway, this boy hit me in my mouth, and I tasted my own blood, and I said, 'No, this game's too tough for me.' And I quit that day."

'I'm Never Gonna Quit Again'

Dean was angry. He called Gene a quitter. He tried to get him to come back.

About a week and a half later, Dean was playing at a neighbor’s house. There was a dog there, a boxer. Dean loved dogs.

"Dean had been playing at this house all day with this dog there," Gene says.

Dean went home for dinner, and then ran right back to the neighbor’s house. But this time, the dog wasn’t so friendly.

"And he bit Dean's arm and took his veins away, and they rushed him to the hospital," Gene says. "Dean died on the table in the emergency room."

The funeral home prepared Dean’s body and put him in a casket. And then, he was taken home. Gene and his mother walked over to Dean’s house to say goodbye.

"I went in the side door. And my Aunt Honey was standing there, and she was crying," Gene says. "She had this white hankie in her hand that had something like curtain frills along the edge of it. She was wiping her eyes. I heard her say, 'Who's gonna be my baby now? Who's gonna be my baby now?' And I looked up at her, and I grabbed her hand, and I said, 'Aunt Honey, I'll be your baby.' And she looked down at me — and I will never forget this — she said, 'You can't be my baby. You're a quitter.' I told her, I said, 'I'm never gonna quit again.' "

And, at least when it came to football, he meant it.

"I went back to junior bantams," Gene says. "I asked if I could wear No. 13, because that was the number that Dean wore."

Later, when Gene became a drug and alcohol counselor — this was decades after he’d retired from the NFL — he’d say to his charges, "Do you know that there once was a black field goal kicker named Gene Mingo?"

They usually said, "No."

But if they asked Gene to tell them more about football, he’d talk about other things.

"I told my story — the drug taking me over, what it did to me, that I had shot my wife," Gene says. "I would always share my story because I was no better than them."

In And Out Of School

When he was 8, Gene’s family moved to a new house in Akron. It was only about three blocks from where they had lived before, but it was in what was considered a "white" neighborhood.

"And they said, 'Oh, here come the n------.' And they thought we were going to have the old, broken down house and cars and everything," Gene says. "We had the best house on the block. Mother didn't allow us to go outside with holes in our blue jeans or shirts or — we had to be respectable when we left the house."

Gene skipped school — a lot. He’d find a way to sneak out, even on the days when his mother delivered him to the front door.

That was before Gene's mom had a series of heart attacks and strokes. By the time he was 13, someone needed to stay home and take care of her. One day, after Gene's father got a call saying that he'd skipped school again...

"He said, 'Son, if you don't like going to school, why don't you stay home and take care of your mother so your sisters can graduate and your brother can go into the Navy?' " Gene explains. "So I said, 'You know, that sounds good to me.' "

Gene took care of his mother for three years. She died in 1954, at the age of 50.

"Even though she was deceased and I was looking at her coffin, I did promise her I would go back to school. And I went back to Lane Elementary School and went to South High School," he says.

By this time, Gene was a couple of years older than the other kids — and a couple of years bigger and stronger. He was the star of the football team, but not of the classroom.

"Then came this southern teacher, the beginning of my junior year," Gene says. "He was writing on the blackboard, and when he got finished, I — as you're supposed to do — I raised my hand to get his attention. And he looked back and said, 'Oh, the big football player. He wants some help.' Just like a tennis match, all the kids’ heads turned at the same time and looked at me. And I was so embarrassed. I just stood up and said, 'To hell with this white man's learning. I'll join the Navy.' "

Gene wanted to "see the world" and “find a new sense of purpose and direction.” Instead, he played football. Back then Navy bases had football teams, and Gene was a star — as a running back, defensive back and field goal kicker.

"And I was big stuff on the base," he says. "I didn't even have to show my ID when I left the base or came back on it, because everybody knew me."

After three years with the Navy, Gene moved back to Akron and got a job at the Goodyear plant where his mother and father had once worked. He figured his football days were over. But, one day in 1960, Gene was reading the paper.

"As good as I could read," he says. "And I saw that the American Football League was being formed. And there was a player out of Fort Carson Army base that had signed with the Broncos."

Gene figured that if an Army player could make the Denver Broncos, so could he. So he decided to write a letter to Broncos general manager, Dean Griffing. He spent a long time on it — looking up words in the dictionary and getting help from his older sister.

He sent his letter to the Denver Broncos, and then he waited.

'I Didn't Know That I Was Going To Make History A Little Later On'

Gene didn’t have to wait long. The AFL was in direct competition with the NFL for players. AFL teams were desperate to sign anyone with experience. Griffing responded personally.

"He sent me a contract for, ah, $6,500. That was in 1960," Gene says. "I signed it right quick. I didn't know that I was going to make history a little later on."

To earn that $6,500 Gene would have to make the team. And that was far from settled. He was one of 100 players who reported to training camp. One day, Gene was laughing and running plays with some of his fellow hopefuls while Broncos head coach Frank Filchock evaluated the team’s kicking prospects.

It wasn’t going well.

"And Coach Filchock stopped the practice. He was down on the lower field," Gene says. "He blew his whistle and he said — excuse my language — but he said, 'God-d, I'm trying to build a f-ing football team, and you guys are up there f-ing off.' And one of my teammates, I believe it was Bill Miller, said, 'Mingo can kick.'

"And so Filchock said, 'Well, if you can kick, come on down here.' And one of my teammates said, 'Man, you better go down there. You know, the more positions you can play, the easier it is for you to make the team.' Well, I went down. I kicked the first ball — it went through beautiful. It had high [trajectory] and it took off and went through. And we moved it back 10 yards, and I kicked another one through. And he moved it over to another hash mark, and I kicked it and it went off to the right, like a golfer's slice. And he said, 'Ah, get out of here.'

"I started to turn and walk away, and something — I heard something in my ear say, 'Don't give up. Go back. Go ask him for another chance.' And that’s exactly what I did."

This time, and every time thereafter, his kicks split the uprights.

Gene says, back then, kicker — like quarterback — was a job reserved for white players.

But Frank Filchock wasn’t worried about that. He wanted to win games. So the team’s trainer, Fred Posey, fitted Gene with a kicking shoe.

"He said, 'Mingo, let me tell you something,' " Gene explains. "He said, 'You are one lucky son-of-a-you-know-what. Because they were going to cut you that Saturday.' "

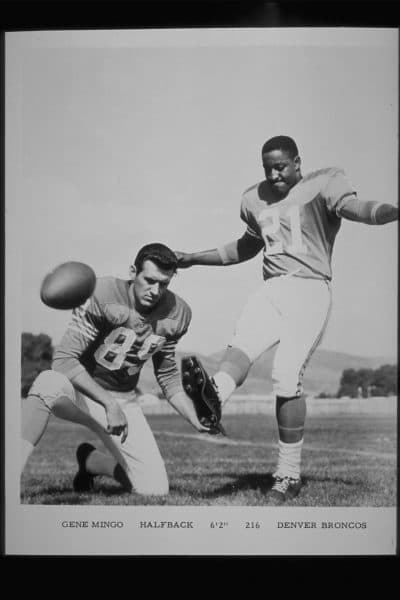

Gene became the first black kicker in the AFL and, later, the NFL. The next black kicker wouldn’t join the league until 1985.

'I Put On A Show For Those People'

Then came Sept. 9, 1960, when the Broncos met the Boston Patriots in the AFL's first regular season game.

"I was sort of jittery and everything. I had to go out and do a job," Gene says. "And I don't remember the score at halftime."

It was 7-3. The Broncos were ahead.

"But anyway, our punt return and kickoff man got hurt," Gene says. "And Filchock was walking around the Quonset hut. He said, 'Mingo, you're running back kickoffs and punt returns.' I was scared. I was nervous. Somebody gave me what they called back then a 'bennie' — it's supposed to brighten you up. Well, I didn't know how bright it was gonna be. When we stepped out of that Quonset hut and the lights of the stadium was so bright, I thought it was daylight."

In the third quarter, Gene returned a punt 76 yards down the sideline for a touchdown. The final score: Denver 13, Boston 10.

But after that 76-yard punt return, Gene was supposed to kick the extra point, right?

"Ah, yeah, you're absolutely right. It was my job to kick the extra point," he says. "Well, I didn't realize how drained I was. I kicked a big divot in the ground. I was mad at myself, but at least running that touchdown back won the game for us."

That day put Gene’s career on a rather unusual path. Because after that, whenever one of his teammates got injured, Gene raised his hand and volunteered to go in.

"We didn’t have that many players," he says. "I ran halfback, I ran fullback, wide receiver, I played defensive back, I ran back punt returns, kickoffs."

Decades later, Lamar Hunt, one of the founders of the AFL, spotted Gene and his wife at a Broncos game. He called his own wife and sons over and said, "I want you all to meet Gene Mingo. This man helped save the American Football League."

"They were coming to see Gene Mingo play. I was an oddity," Gene says. "I went out there like Al Jolson. I put on a show for those people."

'Keep Your Nose Clean'

At the end of that first AFL season, Gene Mingo was the league’s leading scorer, with 123 points. He was also the best kicker in the league, with the highest field goal percentage.

"When I heard they were going to have an All-Star team, I expected my name to be on there," he says.

But it wasn’t.

"I was a little hurt, thrown back, or however you want to say it. I kept wondering, you know, 'You led the league in scoring, what's wrong?' It just broke my heart, that's all," he says.

"Did it feel like it was because of the color of your skin?" I ask.

"It had to be."

That offseason, Gene found himself at his old high school, working out alongside future Hall of Famer Willie Davis. Davis had been following Gene’s career in the AFL.

"He said, 'Let me tell you one thing, Mingo,' " Gene recalls. "He said, 'You may be kicking the ball now. But they don't really want you. You have to keep your nose clean and do what they say, because they don't want a black man playing pro football today.' And that stuck with me. I tried to stay as clean as I could and follow the rules."

When Gene came back to camp in 1961, the Broncos had brought in seven field goal kickers, looking for someone to replace him.

How did Gene respond?

By teaching them how to kick.

"One of my teammates, Chuck Gavin, who has passed away, asked me, he said, 'Mingo, what are you doing? Don't you know they want to take your job?' " Gene remembers. "I said, 'Chuck, they can't outkick me, so why not teach 'em? Until they can outkick me, they ain’t gonna take my job.' That's how much I believed in myself.

"I led the league in scoring again in '62, with 137 points. Wasn't selected to the All-Star team, and some of my teammates said, 'Man, it's a shame they wanna treat you that way.' "

But Gene would have done better to remember the advice Willie Davis gave him after that first season. Because after one incident 1964, many felt that he had not "kept his nose clean."

Gene says it was the beginning of his "unraveling."

"It was something that happened that I had no intentions of having happen, but it did, and I have to own up to that," Gene says. "I had just been married to my second wife for, I believe, six months."

The Broncos were playing in Oakland. That’s where Gene’s wife’s best girlfriend, Edna, lived. She invited Gene and one of his teammates, Willie West, over for dinner.

"Louisiana gumbo, collard greens, corn bread, fried chicken, all southern foods and stuff," Gene says.

Edna invited two of her female coworkers to join them.

After dinner, Gene and Willie’s ride back to the hotel didn’t show. Curfew was fast approaching, so Edna's co-workers offered to drive them instead.

"Time was slipping by, and I said, 'Edna, let them take us back.' And so it was a little VW bug. Willie West and myself, we got in the backseat cramped up," Gene says.

The two women climbed into the front ...

"Driving like a bat out of heck and got us back to the hotel," Gene says. "There was gravel in the parking lot. I guess it made enough noise that two of my teammates heard us pull in and looked out the window, and one girl got out the driver’s seat, and they saw that she was a white girl."

After saying goodbye to the women and going into the hotel, Gene stopped in the hallway to chat with another teammate who was rushing in after a night out. And when Gene got to his room, he says he was surprised to find the women there.

He knew assistant coach Red Miller would arrive any second for bed check.

"I sort of panicked and I said, 'Get in the closet and get in the shower.' That's what they did," Gene says. "Well, Red Miller came to the door, and we act like everything was cool. And I looked at Willie, I sort of whispered, 'Did you invite 'em up?' And he said, 'No, I thought you did.' "

The women stayed. Gene says nothing really happened, though he wanted it to.

And then, about an hour later ...

"Here comes Red Miller back up and knocked on the door and said, 'I hear you have two white girls in your room,' " Gene recalls.

Gene and Willie were told to report to Broncos GM Dean Griffing the next morning.

"I begged the man," Gene says. "I said, 'You know, you were at my wedding.' I said, 'There was no way I expected to come out here and to invite any girl to my room.' I said, 'I'll beat the Oakland Raiders myself if you just give me a chance.' He said, 'No, what y'all did was detrimental to the team.' They put us on the plane before the game even started. And when we got back to the Denver airport, the media were there and my wife was there — Erma was there. That was just it. That was in the '60s. And you know how prejudiced everybody was."

Gene says his white teammates had gotten caught with women in their rooms after bed check, and no one ever got in trouble.

'I Didn't Even Know I Had Played'

The Broncos released Gene, and his career never fully recovered. Neither did his marriage. Erma stayed with him as he played in Oakland and Miami. She had moved back home to Denver by the time Gene was in Washington.

That’s where the last important moment of his football career happened. It was in a game against Philadelphia.

"I kicked off, and Timmy Brown was with the Philadelphia Eagles," Gene explains. "He caught the kickoff and broke through our line of defense. And I was the last guy there. And I hit Timmy Brown from the front. And at the same time I hit Timmy Brown from the front, Chris Hamburg was hitting him from the back. I felt like somebody had hit me in the middle of my head with an ax."

Gene went down — and then he jumped right back up. Later, people told him that he had played a brilliant game, even shouting orders to the offense and defense from the sidelines.

"After the game was over, Brig Owens was around the corner from me," Gene says. "He say, 'Hey Mingo, whatcha gon' do tonight after you shower, man?' I said, 'Well after I shower, I'm going outside and getting my wife and son and take 'em to dinner.' He said, 'You gonna do what?' I said, 'You heard me. I'm gonna go get my wife and son and take 'em to dinner.' He said, 'Doc, you better come take a look at Mingo. His wife and son are in Denver.'

"This was told to me because I didn't know any of it. I wake up in the hospital, a Wednesday afternoon."

Gene was still convinced that he was going to be late for the game, until a doctor handed him a Monday morning newspaper.

"And the headlines in the sporting section read: 'Mingo kicks tying field goal: 35-35.' I didn't even know I had played," Gene says.

That was three days after the game. Gene stayed in the hospital again that night. He was released on Thursday and immediately went to the stadium for practice, but Washington’s coach, Otto Graham, sent him home for one more night of rest.

Gene returned to the stadium on Friday.

"I put on my practice clothes, went out, kicked off, kicked field goals, extra points and everything — feeling pretty good," Gene says. "Went back in, started packing my bags, and the trainer came in. He said, 'Gene,' he says, 'Otto wanna see you in the hallway.' Well, he was laying up against the brick wall there, he had his right leg bracing him on the wall and he had a pad of paper or notebook in his hand. And he didn't look me in my face. He said, 'I'm gonna have to let you go. You kicked too erratic in the game Sunday.' I said, 'I did what?' "

At just that moment, the team doctor came down the hallway, and he overheard the conversation.

"And the doctor said, 'Otto, the man played the game under instinct. He didn't even know he was there.' And even today, all I remember is hitting Timmy Brown and feeling that ax hitting my head. That's what it felt like," Gene says.

"I was so mad. They released me."

That was in '68. In '69, Gene played for the Steelers. They released him, too.

"And I said, 'The hell with it,' " Gene recalls. "I'll just stop playing. You guys don't want me anyway.'

"Karen, do you know I'm the only halfback in NFL history to throw two touchdown passes over 50 yards in a game?" Gene asks. "That I've scored points six different ways? There are not any other players in the NFL that have scored six different ways."

Actually, there were. They’re both in the Hall of Fame.

'That's When Things Got Out Of Hand'

Gene settled in Denver and tried to go back to get his GED, but ...

"Everybody in the classroom were younger than me, but they knew the name Gene Mingo. They looked up to me," he says. "But that looking up to me made me feel just like I was in high school. I was embarrassed. And so I dropped out."

Gene went back again, and dropped out again. He says he felt like he was just a person who couldn’t learn. So he worked jobs that didn’t require a high school diploma. He met a woman named Sally — she’d eventually become his third wife — and got a job driving a cement truck.

"My back started to hurt me, and then that's when things got out of hand," Gene says. "I got involved with using cocaine to help take the pain away from my back. And I learned how to cook it up and smoke it. And in 1986, I was inducted into the Summit County Sports Hall of Fame. Do you know who's in that?"

I have to say, this is not where I thought this story was going. Because in 1986 — it was Sept. 10, 1986, to be exact — something happened that would have a much greater impact on Gene's life.

"So, OK, so I want to talk more about the Hall of Fame in a bit, but first we have to sorta talk about what happened," I tell Gene.

He laughs.

"OK. I told you that I got involved with cocaine. I did it for about a year and a half, almost two years," Gene says. "I bought some cocaine off of this one dealer and evidently it wasn't the same stuff."

"She didn't know I had the gun. And as I was pulling down, protecting her and me, the gun went off. The bullet went into her arm and into her side."

Gene Mingo

When the dealer arrived with the cocaine, he asked Gene to cook it up and share it with him. Gene said 'yes.'

When the drugs were gone, the man asked Gene to cook up some more. But Gene didn't know where his stash was. He'd asked Sally to hide it from him.

"He stormed out of the house," Gene says of the dealer. "And I got sort of afraid. That's what the drug was doing to me. It was making me become paranoid. I got in my car and I went down — I wanted to buy a gun to protect myself and my wife. I went to Dave Cook."

That was a sporting goods store in Denver.

"I was able to buy a gun," Gene continues. "And I loaded it up and I put it in my boot to get in the house. My wife didn't know this. She had fixed dinner, so we sat down and ate dinner."

Afterward, Sally and Gene went into the family room. But Gene was jumpy — watching the door more than the television.

"She knew something was wrong," Gene says. "Well, to make a long story short, I cooked up a little bit more and was doing it. My dog jumped off the bed. I saw his shadow."

Gene grabbed Sally — he says he was trying to protect her.

"She didn't know I had the gun," he says. "And as I was pulling down, protecting her and me, the gun went off. The bullet went into her arm and into her side."

Sally was rushed to the hospital and into surgery. Gene was taken to the police station and booked. He didn’t know if Sally was dead or alive.

"I was crying so hard that I fell asleep," Gene says. "And when I woke up, it was a half-hour later. The reason I woke up, I was hearing voices in that jail cell. And I knew where I was, and I said — 'What? Who? How could?' And I heard the voices: 'Everything's going to be OK. We're here. Take it easy. It'll be all right.' And I begin to open my eyes. And my mother was standing to the right. My dad was standing next to her."

Gene says the figures in his jail cell were all looking off to the side, at the same thing.

"And I started to turn my head and I began to see this white, creamy robe with this braided sash," Gene says. "And I started to look a little further to the top of the shoulder and I began to see this dark, brown, satin, silky-looking hair. Karen, I believe I looked in the face of God. And all he did was smiled at me."

Life As A Counselor

Gene never took cocaine again. The most serious charges against him were dropped after Sally’s decision not to cooperate with the prosecution. Months later, Sally spoke on Gene’s behalf in open court, and Gene was sentenced to two years’ probation.

The bullet had lodged near Sally’s spine. Doctors told her she’d never get full mobility back in her arm and shoulder. But slowly, over time, and with the help of a therapist, Gene and Sally rebuilt their relationship.

Every time I spoke with Gene on the phone, Sally was in the background, making sure he didn’t forget to tell me anything important.

As part of his probation, Gene was required to find a job. The probation office suggested he try at an addiction treatment facility in Denver. He met with the doctor in charge — hoping that maybe they’d hire him to work in public relations. Instead, the doctor asked if he’d be interested in becoming a counselor.

"I said, 'Doc, you have to have your college diploma for that don't — ' He said, 'No, all you have to have is a GED.' And I looked at him, and I said, 'Doc, I don't even have that.' "

So, Gene went back to school — to the same place where he had failed to earn his GED twice before. This time, he says, he had a purpose, a reason to push through the embarrassment. He earned his GED and moved on to get his certification as a drug and alcohol counselor.

"Do you know I didn't get less than a 95 on the majority of my tests?" he asks. "And there was a time in my life that I didn't think I could learn."

Gene went on to work as a counselor for a decade. Then he helped families hold interventions. He says he’s now recognized as often by those who want to thank him for that work as he is by those who remember what he did on the football field.

But Gene didn’t start taking cocaine because he wanted to get high. He started taking it because he wanted to get rid of the pain. And when he got clean, the pain came back.

"Do you know I've had five back operations and I've had three neck surgeries? Because Otto Graham and the Washington Redskins didn't tell me how bad it was," Gene says. "They didn’t let me know anything. All they did was let me come home. That's all they did was cut me loose and let me come home."

It wasn’t until decades later, after he’d retired from the league, that a doctor stood Gene and Sally in front of an X-ray and showed them where the pain came from.

"And he looked at me. This doctor had tears in his eyes," Gene says. "He said, 'You're one lucky fella. You see this spot here? All somebody had to do was come up and tap you on the back to say "hello" to you, and you could have been paralyzed the rest of your life.' That's how bad it was. But the Redskins didn't tell me.

"I'm a little upset. I get upset with the Redskins. And I hear the NFL talking about concussions. I don't know how many concussions I had playing football, but it was for these owners to make these billions of dollars that they're making. And they're waiting for some of us old players to drop dead so they don't have to pay us and — I have nothing to say."

Recognizing Gene Mingo

When Gene and I spoke on the phone before our interview, I warned him that I’d be asking about his whole life — not just his time on the football field. He said, "Ask me whatever you need to ask. I don’t mind."

And with everything we talked about, only two subjects made him angry: how Washington treated him after his injury and — the issue that brought me to him in the first place – the question of whether he belongs in the Hall of Fame.

"The reason I'm hurt," he explains, "everywhere I go, I hear somebody tell me, 'Boy, you were a hell of a player. You should be in the Canton Hall of Fame.' Wouldn't you get tired of hearing that when you know what you've done? You would get tired of hearing people tell you, 'You should be in the Hall of Fame.' "

After all of his successes and failures, the barriers he broke down and the mistakes he made, is it any wonder that what Gene Mingo most wants now is to be remembered?

"I’ll be 80 years old Sept. 22, if I make it that far," Gene says. "There's people out there that know what I've done. But unless people from my era speak up, or whatever, Gene Mingo may not never be recognized."

You can read more about Gene Mingo's life in his autobiography, "What Have You Done Now, Eugene?"

This segment aired on January 20, 2018.