Advertisement

'A Total Failure' — North Korea's Attempt To Rival The '88 Olympics

Resume

In terms of history, it may turn out the most significant moments at the 2018 Winter Olympics occurred during the opening ceremonies when athletes from both North and South Korea marched under a unified flag.

The Winter Games in South Korea have included the North Koreans, or at least a select few of them.

North Korean cheerleaders, resplendent in red and beaming in unison, brought enthusiasm, even to games that were hopelessly one-sided.

North Korean women joined their South Korean counterparts to create a unified women’s hockey team that lost hopelessly one-sided games.

North Korea’s leader even sent his sister to shake hands with the president of South Korea.

Was the participation of athletes and cheerleaders from North Korea a good idea?

Yes, if you believe any contact between the two regimes is better than none. No, if your main concern is that even minimal inclusion provided North Korea with propaganda opportunities for its repressive regime.

But regarding the last time North Korea tried to shoulder its way into the spotlight shining on international competition, there’s perhaps no debate about their success.

'That Just Drove Them Crazy'

Return, now, with journalist Bradley Martin and me to 1988, when South Korea played host to the Summer Games, while North Korea fumed.

"Well, the North Koreans were going berserk. They could see that they were losing the economic race," Martin says. "Up until the '70s, they had thought that they were ahead of South Korea, and they did do a pretty good job of building their economy on the communist system. But then that started to flag. So it was a rough time for the North Koreans, and they particularly envied the South Koreans their 1988 Summer Olympics. That just drove them crazy."

Maybe “crazy” explains how North Korea chose to respond to those ’88 Summer Games in Seoul after their offer to co-host the show was rejected. The leadership of North Korea figured they’d stage their own games.

"It was sort of an Olympics for the socialist bloc, and that included a lot of social democratic-ruled countries in Europe," Martin says.

It wasn’t a new idea. The World Festival of Youth and Students had been staged in Prague, East Berlin, Moscow and Havana, among other cities. Pyongyang might have seemed the next logical place to showcase the talents of young athletes from communist countries, if not for the early departure of logic from the proceedings.

Absent the help the Soviet Union couldn’t or wouldn’t continue to provide, the North Korean economy was a wreck. But when Bradley Martin arrived on assignment from Newsweek before the World Festival of Youth and Students opened, he saw that the host nation’s ambitions were grand.

"I mean, there were all these skyscraper apartments — whole district of them," Martin says. "And the plan was for the delegates to stay there first, and then the high-rise apartments would be turned over to ordinary people. And there were all the venues: wonderful stadiums and that sort of thing."

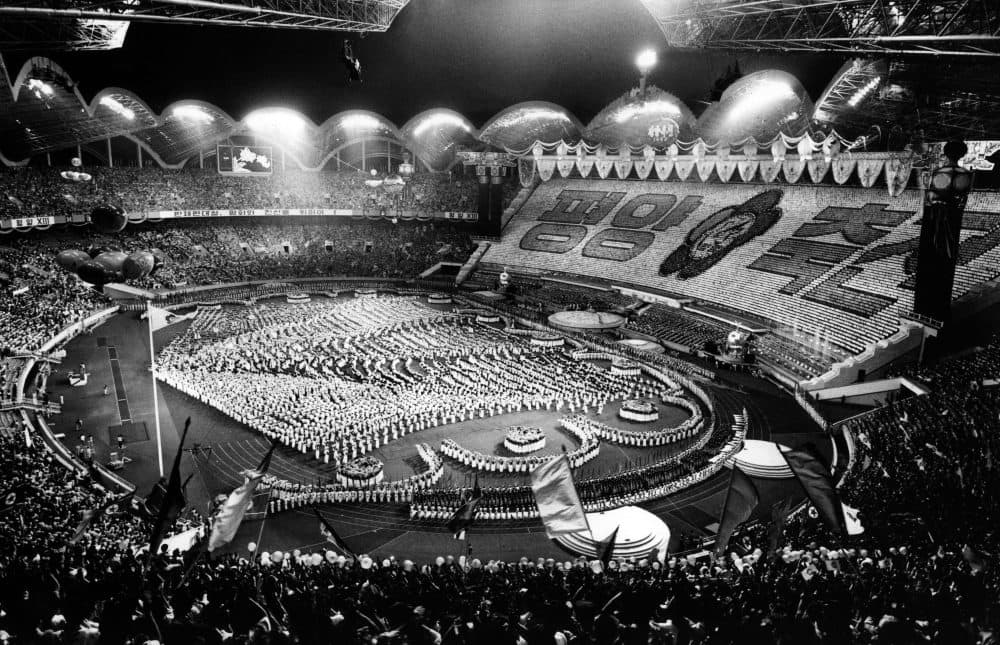

The "stadiums and that sort of thing" had been built by a mass labor campaign. The main stadium, with a capacity of 150,000 people, was particularly impressive, but it was dwarfed — at least vertically — by the 105-story hotel that was allegedly almost finished when the athletes, their entourages and the journalists arrived in July.

Bradley Martin was present for the opening ceremonies, during which scores of birds were released into the sky over Pyongyang. The soldiers in attendance were perhaps too quick to fire off a traditional salute.

"The birds went crazy. They were so upset," Martin recalls. "It was really, I felt, rather ironic at the time. It struck me as symbolic, because the country still was and still is totally militaristic. That’s the emphasis there."

Once the terrified birds had fled the scene or — perhaps — fallen, lifeless, from the sky, the games began. Basketball and volleyball were among the attractions, as were juggling, acrobatics, various circus acts and musical performances.

The festival also included political discussions — so after checking out some spear throwing, it was off to the "anti-imperialist tribunal" or the "solidarity rally with people, youth and students of Nicaragua."

'It Was Total Control' — And 'Total Failure'

Though the spectacle likely dazzled some onlookers, Bradley Martin had a job to do. He’d heard about an upcoming human rights demonstration, which would be a large deal in a nation opposed to such things, so he tried to find the planning meeting.

"And the taxi driver took us out in the country for an hour or two and pretended he was lost," Martin says. "He did not want us to go over there and gather that news. It was total control. And it always has been."

But there were limits to "total control," even in Pyongyang, in part because the North Koreans hadn’t closed their festival to delegates from nations less totally controlled than their own.

"The visitors were all playing rock 'n' roll on their little boomboxes. And the North Koreans had never heard such a thing," Martin says. "So they were out there shaking their booty and just having a great time. And I thought, 'Wait a minute. You know, this is the beginning of what the North Korean rulers do not want to see.' People were starting to realize, 'Hey, this is kind of fun, what they’ve got over there in those horrible, capitalist, imperialist countries that we keep hearing so much about.' ”

"Basically what we’re seeing here is the most obvious North Korean charm offensive."

Bradley Martin on North Korea's showing at the 2018 Olympics

The infestation of the devil’s music — or at least the music of the imperialist great Satan — wasn’t the only problem for the North Korean elite. The billions of dollars spent on the spectacle was money North Korea didn’t have. And although the enormous stadium built for the World Festival of Youth and Students is still used for soccer matches and choreographed demonstrations, the 105-story hotel still isn’t finished.

And as for the district of skyscraper apartments?

"Today no one wants to live there," Martin says. "Because you have to take an elevator to get up there, and there’s very little electrical power available in North Korea. So, if you have one of those apartments, you’re basically stuck there.

"It was a total failure. First, it finished wrecking the economy. I mean, they spent so much money on this. And meanwhile they had defaulted on their debts to Western countries and the Soviet Union from the '70s. So the world’s financial community said, 'What are these guys doing? They’re going and spending this money that they won’t give back to us.' And look, what are they getting out of it? Basically nothing, in terms of productivity or any lasting good thing for their economy. So it was sort of the last hurrah before the economy collapsed in the 1990s. Totally collapsed."

'North Korean Charm Offensive'

Any number of Western cities seduced into thinking that hosting the Olympics or the World Cup would be beneficial in the long run can sympathize. Think Montreal, 1976. The Canadians finally finished paying for those games 30 years later. Or think Rio 2016, where the construction of venues currently derelict has left an already-struggling economy with an additional debt of at least $40 million.

But North Korea’s 1989 boondoggle was apparently colossal, even Olympian, at least according to Martin, whose reporting got back to the North Koreans.

"Somebody in New York kept putting the term 'personality cult' into my cover story. It was in there about three or four times," he says. "And that offended the North Koreans so much that I was put on a blacklist."

Martin was not allowed back for another three years, at which point he continued to be unimpressed by the place, or at least by the sincerity of its leaders. And he’s no fan of the nation’s appearance in the Games to the south.

"Basically what we’re seeing here is the most obvious North Korean charm offensive," Martin says. "I’ve studied North Korea long enough to know that what North Korea wants to do is to conquer South Korea. That’s the ultimate goal of North Korea. And every now and then, they’ll put on one of these charm offensives, and it works. It works.

"It gets lots of starry-eyed young people thinking, 'Oh, peace. We can have peace if only the evil Americans would get their troops out of South Korea.' So, basically, I thought the whole thing was a charade."

So at least one guy who’s been to Pyongyang, seen that great, big unfinished hotel and been driven around the countryside by a taxi driver playing dumb isn’t buying the cheerful cheerleaders and "let’s play hockey together."

It’s safe to say he’d have been happier if the North Koreans had stayed home.

We first learned about the 1989 World Festival of Youth and Students from The New York Times article "North Korea’s Would-Be Olympics: A Tale of a Cold War Boondoggle." For more on Bradley Martin's adventures in North Korea, check out his book "Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty."

This segment aired on February 24, 2018.