Advertisement

The Pickup Basketball Game That Led To A Nobel Prize

Resume

To understand the friendship between Michael Rosbash and Jeff Hall, it’s best to start with one very famous baseball game in the fall of 1975.

"You want the short, medium or long version?" asks Rosbash. "Long version, right. It was my first year at Brandeis. Jeff Hall, he started a few months before I did."

"When we first met, I realized almost immediately that we were kind of simpatico," Hall says. "Michael was working on nucleic acids, DNAs and RNAs. And I was working on genetic variants in drosophila."

Drosophila are what you and I might call fruit flies.

"And so our professional interests overlapped," Hall says. "It all comes under the broad heading of genetics."

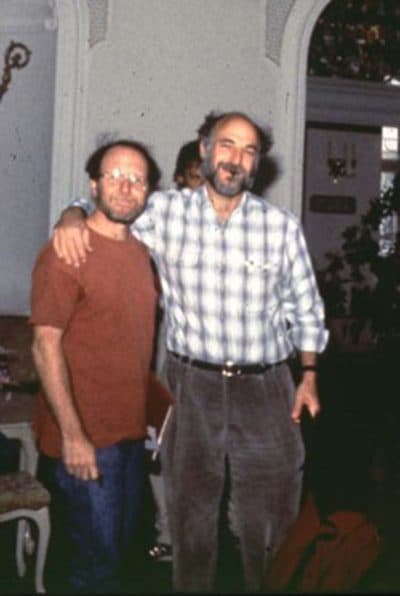

Hall and Rosbash liked a lot of the same things.

"Pop music, beer drinking, profanity, misbehavior," Hall says. "And we were looked upon askance by the more sophisticated, tweed jacket-wearing professor types."

The other thing that set Hall and Rosbash apart was their love of sports — which brings us to the fall of 1975 and that famous game.

'What Can I Say? We Were Idiots'

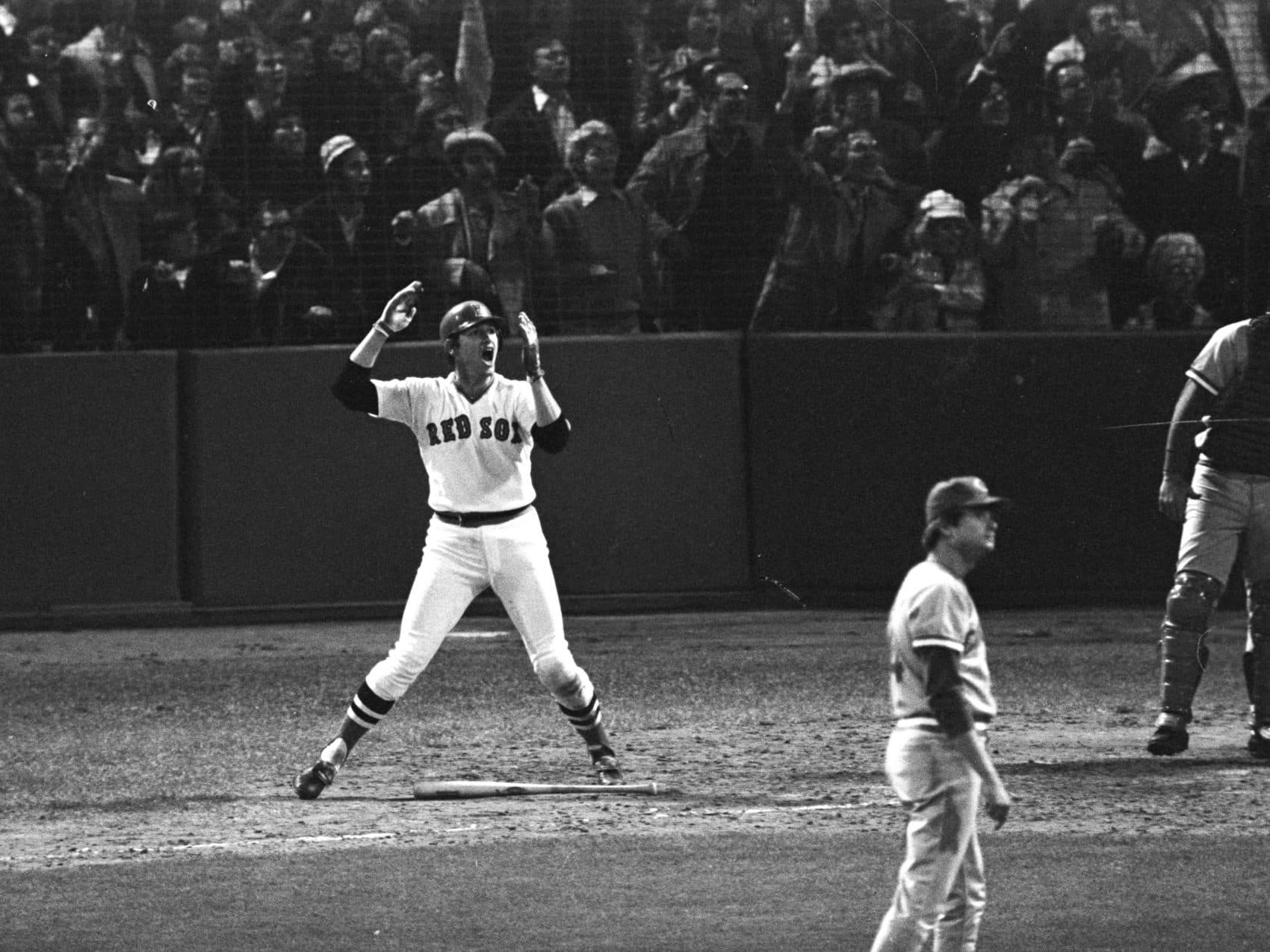

The Red Sox started that season as a long shot even to make the playoffs. But come October, they faced the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.

Michael Rosbash entered the lottery for tickets, and won the right to purchase two seats for Game 6 at Fenway Park. By the time the game came around, the Sox were down three games to two. But still, hopes were high.

"So Jeff and I went down to see the game. It was rained out."

It rained for three days straight. "Finally, they played the game," Rosbash says. "We're in the bleachers."

"God, we were so enthusiastic when the Red Sox went ahead early," Hall says.

But in the fifth inning, the Reds tied it up. Then they went ahead by two in the seventh.

"But I remember, when you're starting to try to get your research going, it's not easy to do. It wasn’t going very well. So we weren't in a very good frame of mind," Hall says. "And now it made it even worse, because, my God, it looks like they're going to lose this game.

"And then, finally, I'll never forget, in the top of the eighth inning, this flat, mediocre non-entity for the Cincinnati Reds came to the plate."

Advertisement

His name was Cesar Geronimo. He won the Gold Glove that year, and he was a decent hitter, too.

"And he hit a long line drive near the Pesky pole into the stands to make it 6-3," Hall says. "Michael and I looked at each other and said, 'It's over.' "

"'It'll be too painful to see the Red Sox lose,' " Rosbash remembers. "And so we just couldn't do it. And so we got up and left."

"Just stormed out," Hall says, laughing.

Rosbash and Hall got into their car and drove west, toward the Brandeis campus.

"And as we were driving home, listening to the game on the radio, the game was hanging in the balance, 6-6," Hall says.

“Carbo hits a high drive! Deep center! Home run!"

Bernie Carbo had knocked in a three-run homer for the Sox.

"And then we watched on TV at home through the extra innings," Rosbash says.

"And there were all these remarkable extra inning plays," Hall says. "One of the announcers, he was commenting on all the tension and the drama. And he said, 'This crowd has been up and down and up and down...' "

"...they're drained. Nobody, obviously, has left the ballpark!"

"I turned to Jeff and said, 'I beg to differ,' " Rosbash says.

Any true sports fan knows what happened next. In the bottom of the 12th, Carlton Fisk hit a home run off the left field foul pole. Red Sox win. There would be a seventh game of the 1975 World Series.

"This is perhaps the best World Series game ever. And we had left," Jeff says.

"What can I say? We were idiots," Michael says. "And we spent the whole next week telling everyone what happened to us because this is a scientific commitment to honesty. So we couldn't just say, 'Oh yeah, it was great.' No, we had to say, 'Nah, I got something to tell you.' "

Basketball And Circadian Rhythms

Seven years would pass before Rosbach's and Hall’s dual loves of science and sports would collide again in a big way. This time it happened on the basketball court.

"Michael has told the story about how the reason we got into research was via pickup basketball games, and that's a bit overstated," Hall says.

The year was 1982. Rosbash and Hall were in the habit of playing pickup basketball games at the gym at Brandeis. They’d play with other professors and grad students and with a group of workers from the phone company. And after those games, in the locker room...

"Well, let me put it this way: On Monday morning, the AT&T guys would often discuss in graphic detail their exploits, their dates, from the weekend," Rosbash says.

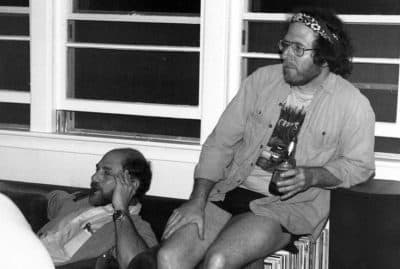

Rosbash and Hall sat one row over in the locker room. And their conversations often concerned genetics. Remember, Jeff’s research had to do with fruit flies.

"Fruit flies have an elaborate courtship ritual. The male sings a song to the female," Rosbash explains.

So while the AT&T guys talked about human mating rituals, Rosbash and Hall would discuss the mating rituals of fruit flies.

Hall was fascinated with research he became familiar with while doing his post-doc at Cal Tech. It had to do with fruit flies and the circadian rhythms that regulate sleep-wake cycles. But Rosbash says nobody understood what mechanism actually kept that biological clock running. He compares it to not understanding how a watch works.

"What is the quartz crystal? Or if you like, what are the gears? How are the gears connected together?" Rosbash asks.

During those locker room conversations, Jeff Hall would bring up this research. He thought it was time someone did something with it. Rosbash felt like he knew how it could be moved forward.

"I said, 'We should really clone this gene, Jeff,' " Rosbash says. "'We do this in our lab, and I think if we collaborate, we could make some progress here.' He said, 'I agree.' "

Rosbash knew how to clone genes. Hall knew about fruit flies. But as they worked together, their skills grew.

"You know, it's like a guy playing basketball who's got very limited skills at the outset," Rosbash says. "A power forward, a center. And then as he acquires more and more ball skills, you end up with someone like Magic [Johnson], you know, who can play point guard as well as inside, and so forth and so on. So that would be an analogy as the years clicked by."

Rosbash and Hall identified and sequenced the gene that regulates the circadian rhythms in fruit flies. They figured out how that biological clock worked. And then came the really fortunate discovery: The same gene was at work in humans. That meant the research could be applied to studying and solving human sleep disorders.

"It could have been that the fruit fly would have a different mechanism," Rosbash says. "You know, the fruit fly would have an analog clock and humans would have a quartz crystal. And then nobody would give a damn about the fruit fly clock."

Rosbas's and Hall's last major discovery was made in 1999. A decade later, their work began to gain recognition.

"The first prize we won in 2009, when I got the phone call, I actually didn't know what the nature of the prize was," Rosbash remembers. "I was rapidly Googling as I said, 'Oh, how wonderful, thank you very much' and so on and so forth — not wanting to appear to be an idiot."

"It's like a guy playing basketball who's got very limited skills at the outset. A power forward, a center. And then as he acquires more and more ball skills, you end up with someone like Magic [Johnson], you know, who can play point guard as well as inside."

Michael Rosbash

It was the Gruber Prize. It comes with an unrestricted cash award of $500,000. By then, Jeff Hall had retired to a cabin in rural Maine.

"I said, 'Michael, you don't need it. You're a highly paid employed person. I'm unemployed, zero paid person,' " Hall says. "'I need the money.' "

Last October, Michael Rosbash received another call. And this one needed no explanation.

"I knew when I went to bed that night that the next morning was the prize, but we'd been several years since we had won anything," Rosbash says. "My wife said to me as we went upstairs, she said, 'Forget it. You guys are toast. It's over.'"

The phone rang at 5:10 a.m. Eastern time — mid-day in Sweden.

"And they woke me out of a deep sleep, which is also not great for your physiology," Rosbash says.

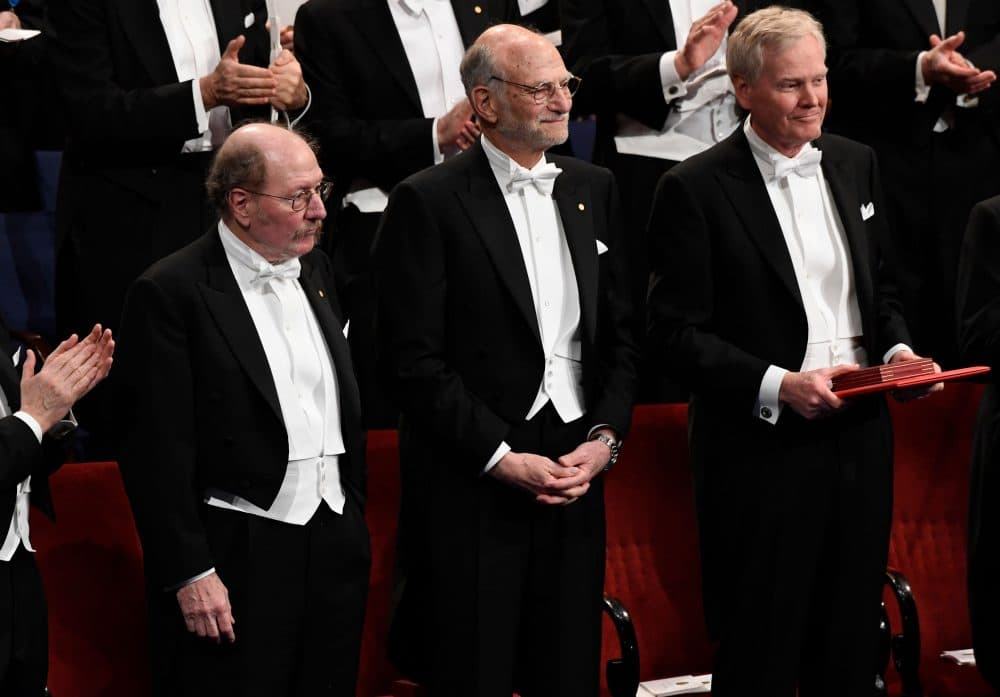

Michael Rosbash and Jeffrey Hall — along with Michael W. Young, who independently pursued similar research at Rockefeller University — had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

"I was absolutely thunderstruck," Rosbash says. "I was a bit at a loss for words, for equilibrium."

Hall was even more surprised to receive the news. The man on the other end of the line apologized for calling before dawn.

"And I said, 'Well, this is going to be pathetic, I'm old,' " Hall says. "Old people tend to go to bed early and get up early. I had been up for an hour. I don't want to get up at 4 in the morning, but I do."

Rosbash admits he’s embellished the story of his locker room conversations with Hall over the years. That academic commitment to honesty gets old after a while. But, if not for sports, would the two have embarked on the research that brought them the Nobel Prize?

"We were very good friends. If we hadn't played basketball, we would have had the conversation in a pub, or over coffee, in the lab," Rosbash says. "It's poignant — poetic, if you like — for two sports-obsessed faculty members to have had the conversation in that venue. You know, it's nice for us. But I think it would have happened anyway."

This segment aired on March 17, 2018.