Advertisement

Life And Lessons Of Bricklayer Bill, The 1917 Boston Marathon Champ

Resume

Growing up, Patrick Kennedy was often asked if he was related to those Kennedys. You know, JFK, RFK, Ted?

He’s not.

"Correct. Not related to the more famous Kennedys," Patrick says. "Or, I like to say, they're not related to us, you know."

But there is one famous Kennedy in Patrick’s family line. He was known as "Bricklayer Bill."

Patrick didn’t know much about his most famous relative, until one night in 2010, when Patrick was out to dinner with his family. A distant cousin named Ann Louise was there. She was in her 80s, and she had grown up knowing Bill.

"Ann Louise, out of the blue, said, you know, 'He gave me a manuscript.' And we all dropped our forks and just were dumbfounded," says Lawrence Kennedy, Patrick's father.

It took Ann Louise a little while, but eventually she found the manuscript in her basement.

Or she found most of it. She’d set one chapter aside, for safekeeping. Then she lost it. It wasn’t found until after her death. Anyway ...

"I got it from Ann Louise, came home," Patrick says. "I remember my wife was making pasta and I sat there in the kitchen, reading every page, you know, in one sitting."

The manuscript was 75 or 80 pages — full of mistakes and typos, with notes and corrections in the margins. Patrick says his great-granduncle was a talented writer, even though he probably never finished high school.

"He read widely, he quoted poems, he quoted Kipling and Shakespeare," Patrick says.

And this is how Patrick first read the words of Bill Kennedy, born in 1883:

Bill’s manuscript was full of little stories. Like the one about his encounter with a "stylishly dressed woman" named Mrs. Levy, who approached Bill and a group of fellow marathoners in the lobby of New York’s Long Beach Hotel.

You may wonder, as did Mrs. Levy, why men run so far for a medal or trophy. … Other questions so often asked are "What do you think of along the road?" "Are you not afraid you will drop dead running so far?" and the commercial one so often asked, "Don’t you get paid for running?"

Working-Class Marathoners

Bill’s running obsession began in 1896. Months after the first Olympic marathon was held in Athens, Greece, the first U.S. marathon ran through Bill’s hometown of Port Chester, New York.

"When the leaders were running through, he and his friends jumped in and ran alongside them and saw them off at the railroad bridge out of town," Patrick says.

Bill became a bricklayer, like his father. He moved west and settled in St. Louis, which is where he witnessed the 1904 Summer Olympics and finally decided to give marathoning a try.

"And that kinda became his passion," Patrick says.

In the early days of the sport, races were sponsored by posh athletic clubs, and they were strictly amateur. But most of the men who ran the long-distance races weren’t posh at all.

"Plumbers, carpenters, other bricklayers," Patrick says. "You know, the bulk of them were, kind of, working-class guys."

The athletic clubs would sponsor runners, paying their travel expenses. But you had to establish yourself as a contender first.

A train ticket could cost a week’s wages. So...

"[Bill] would hobo, just take freight cars or ride on the top of a baggage car," Lawrence says. "Any way that he could. He really didn't have the money, and he really didn't like to pay the money."

The weather was mild in St. Louis, so I crossed the bridge to E. St. Louis and climbed into a boxcar. After sundown the wind shifted north and it was down to zero by the time we reached Decatur, Ill. The next evening, with the thermometer at 10 below, I rode a box car to Chicago, jogging back and forth to keep from freezing. At every stop, the end brakeman walked up to my Pullman banging on the door. He would shout, "Are you awake Brickey?" "Yes Sir." "Don’t go to sleep or you will never wake up."

Get Back Up And Keep Running

Sitting at his kitchen table that evening, reading that manuscript for the first time, Patrick came across one story so unexpected that he pushed aside Bill’s tattered pages and pulled out his computer.

"I went right to the Library of Congress website and I found, sure enough, front page ..." Patrick says.

The year was 1909. Bill was in Des Moines, Iowa, working on the Des Moines Coliseum. It was towards the end of the project, and Bill was leaning out over the sidewalk, scraping excess mortar from the south wall.

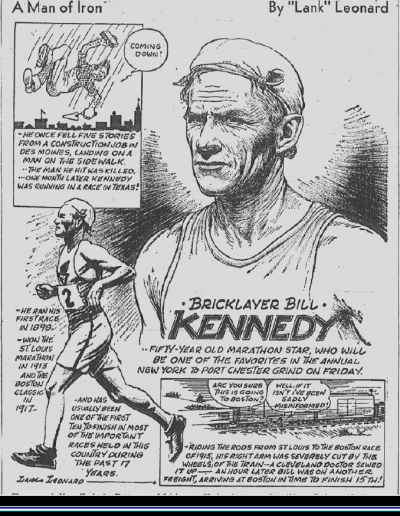

"A gust of wind blew him off the roof. He fell five stories. It was a 65-foot fall," Patrick says. "There was a pedestrian walking right underneath him. Bill landed on him and killed the poor guy. At first they thought that Bill died, too. Then they went over and saw that he was still breathing. He went to the hospital. He survived.

Bill didn’t have much to say about the incident.

"He didn't go into how he felt or anything like that," Patrick says. "The way he put it was, 'My number wasn't up that day.' And the next paragraph he says, 'After I recovered, I realized I was fit enough to keep running.' That was pretty much his first concern."

This would be a theme in Bill’s life. No matter how far he fell — literally or figuratively — he would get up. And when he did, his first thought would turn to running.

"Nobody had ever won the Boston Marathon over the age of 30, so he clearly wasn't considered to be one of the favorites."

Lawrence Kennedy

It happened again in 1913.

"He had had such a great year — I think it was something like in the space of 10 weeks he had won two marathons and several shorter races," Patrick says. "And then that fall, he was stricken with typhoid fever."

This was before the days of penicillin. Typhoid fever could be deadly. Bill was in the hospital for more than three months. He survived.

"But the way one of the Chicago papers put it was that he was hollowed out; he was a shell of his former self," Patrick says.

Patrick says Bill appeared to age decades in just a few months. His face became wrinkled. His hair turned gray.

"Actually my dad went gray pretty early, but I think in Bill's case it was triggered by the typhoid," Patrick says.

Nobody expected Bill to return to the marathon circuit.

"Most of the doctors at the hospital told him, 'Yeah, your running days are over,'" Patrick says. "But then he told this one doctor:

As soon as I was able I would have to go back to laying brick, which was hard manual labor for eight hours, while the marathon took less than three hours. On the job you had a boss breathing down the back of your neck, and racing you had a cheery word and the applause of the crowd. So Doc says, "You got something there. Go to it. And good luck."

'He Clearly Wasn't Considered To Be One Of The Favorites'

Bill recovered well enough to run the Boston Marathon in 1915. But his running club had cut him loose, thinking his best days were over.

He rode the rails and arrived with nothing more than his running clothes wrapped in paper. After a bath, he walked down to "newspaper row" where Boston’ s nine daily papers were located.

Larry was astonished when I told him how I got to Boston. He called Mr. Barnes, his boss, to whom I had to repeat my story.

"That is actually how Bill gains his fame," Patrick says.

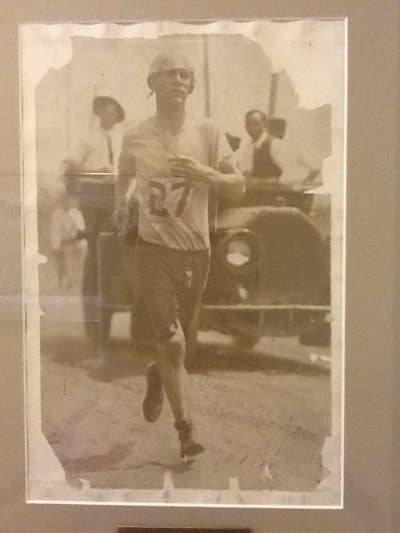

By the time Bill lined up at the start of the Boston Marathon in 1917, wearing a stars and stripes bandana, he was 33 years old. Lawrence says the papers rounded up to 35.

"Nobody had ever won the Boston Marathon over the age of 30, so he clearly wasn't considered to be one of the favorites," Lawrence explains.

"The guys who were favored to win were a couple Finnish runners," Patrick says. "The only question was which one of them is gonna win."

Marathons are difficult to predict. And Bill was much younger and fitter than he looked. He took the lead after less than 10 miles.

"There was some risk that he had run too hard, too soon," Patrick says. "And sure enough, here he is in Brookline, on a downward slope. That's when he started to fade. Almost got dizzy and weak and felt like his legs were lead."

Marathoners call it hitting the wall. And Bill hit it hard.

His marathon might have been lost, if not for a newspaper reporter in a chase car who noticed the leader was slowing down and shouted at him to speed up.

Bill crossed the finish line first, in 2 hours, 28 minutes and 37 seconds. He told reporters:

It’s great to win the marathon, but it doesn’t buy any steaks or potatoes or onions these days. And there’s Mrs. Kennedy and the two little Kennedys out there in Chicago.

'Keep Picking 'Em Up'

The next morning, Bill returned to work at the bricklaying job he’d taken in Boston to pay his expenses while he was in town.

"But then it started raining. They called off work for the day, and then he went to newspaper row and talked to this guy, Spargo, this sports columnist," Patrick says.

Bill had a habit of seeking out reporters when he had something to say. And on this afternoon, he was apparently feeling philosophical.

He compared marathoning with the daily grind of men like him — men who struggled to feed their families on $12 or $14 a week.

Many a times that man realizes he is on the toughest Marathon in this life, but the right fellow never quits. He goes on trying his best when his better judgment tells him he’s up against it. I know, believe me, for I’ve been over those jumps myself.

Bill ran more than 100 marathons, retiring from the sport at 57. He continued to lay brick into his 70s.

A few years before his death at the age of 84, Bill decided to sit down at that manual typewriter and share what he’d learned over decades of running. He wrote 26 chapters, one for each mile of the marathon. Some of his stories still contain good lessons. Like this one:

Feeling rather chesty after doing five miles under twenty-six minutes, I turned to Mr. Wilson, our coach. "How am I doing, Coach? Am I laying ‘em down all right?"

"Never mind how you lay them down, keep picking them up," was his reply.

Later on that evening, thinking of his remark, it dawned on me. "Why sure, that’s the secret of running: Keep picking them up." And I smiled at the thought — they go down on their own.

Bill’s manuscript was never published. But if it had been, it would have been called, "Keep Picking ‘Em Up." Lawrence finds the title fitting.

"I think that's what he did in his life, he says. "He just kept going and kept going forward."

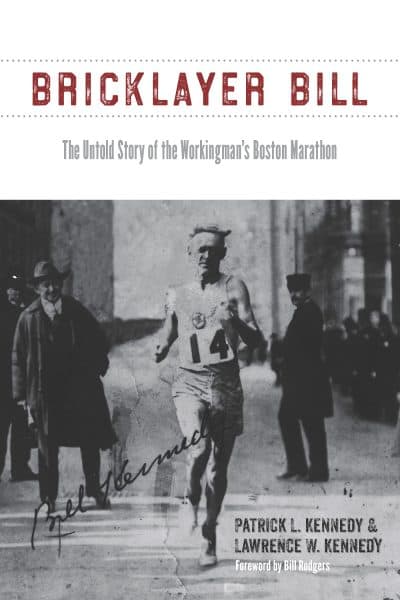

Learn more about the life of Bill Kennedy in Patrick and Lawrence Kennedy's book, "Bricklayer Bill: The Untold Story of the Workingman’s Boston Marathon."

Listen to our readings of Bill Kennedy's manuscript by clicking the play button next to the headline at the top of the page. Thanks to our actor: Mike Lovell.

This segment aired on April 14, 2018.