Advertisement

UNC Stadium Honoree Was Captain In Wilmington Massacre

Resume

If you spend even a little bit of time at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, it won’t be long before you hear a certain last name.

"The name 'Kenan' is very prominent on the campus," UNC history professor William Sturkey says.

"We have dozens of named professorships, 'Kenan Professors,' " says history professor Harry Watson. "We have a Kenan arts center."

There’s also Kenan Memorial Stadium, the home of the North Carolina Tar Heels football team since 1927. But, despite the ubiquity of the name, few students at UNC know much about the Kenans.

In many ways, the Kenans’ history is a lot like that of every other old rich family connected to any other university.

"One of the Kenans ceremoniously gave a brick in 1793, or about then, that was used to help establish the University or help expand the University during its early years," Sturkey says.

(Sturkey notes that the brick was accompanied by a financial contribution.)

"The Kenan family has been prominent in the state of North Carolina since at least the 18th century," Sturkey says. "They were major landowners and major slaveholders in the eastern part of the state."

At this point you may think you know where this is going. A southern university, a slave-owning family, some old buildings with their names on them, and you have all of the ingredients for a 21st Century culture war. But that’s not exactly the case here.

Almost everything named "Kenan" at UNC was named after industrialist William Rand Kenan Jr. — class of 1894 — who gave nearly $100 million to the University.

But when it came time to name the new football stadium in 1927, William Rand Kenan Jr. did not want it named after himself.

"He dedicated the stadium to his father, William Rand Kenan Sr., who was the son of the last generation of slave owners in the family," Sturkey says. "I think the most consequential act in his life — at least in terms of consequences for other peoples' lives and for state politics — was his participation in the 1898 Wilmington Massacre."

Advertisement

The Wilmington Massacre

To understand the Wilmington Massacre, it’s important to understand the political climate that led to it. The 15th Amendment, giving black men the right to vote, was ratified in 1870. Almost immediately there was a backlash. Poll taxes, literacy tests and intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan were largely successful in preventing blacks from gaining political power — but not everywhere.

In some places, such as eastern North Carolina, blacks gained considerable political power during Reconstruction. Like in Wilmington, then North Carolina’s largest city.

Watson explains that there, a coalition of poor white populists and poor black Republicans took control of the city’s government.

"Which was extremely unwelcome to the white establishment that dominated the Democratic Party in those days," Watson says.

Blacks and their political allies controlled the mayor’s office, the city council and the police force. There was even a black-owned newspaper, The Daily Record, which rivaled the white-owned Wilmington Messenger for influence. The situation in Wilmington was, in most respects, exactly what the passage of the 15th Amendment had promised.

"And in Wilmington — which is where the majority of black political power was concentrated — a group of wealthy whites, including William Rand Kenan Sr., essentially decided that they were going to overthrow this government that was influenced by black voters," Sturkey says.

"So they basically staged a coup d'etat," Watson says.

That’s not hyperbole. It was a literal coup d’etat. The only successful one to ever take place on American soil.

"They armed themselves, surrounded the city hall and told the government inside — the city council — that they would have to resign one man at a time and elect a replacement member according to the dictates of this mob," Watson says.

White Democrats took control of the city under threat of force. That threat would soon turn to reality.

"The next day, the mob reassembled and marched on the black-owned newspaper and burned it to the ground," Watson says.

The burning of the Record was just the beginning of the violence. And William Rand Kenan Sr. played a particularly significant — and deadly role — in what followed.

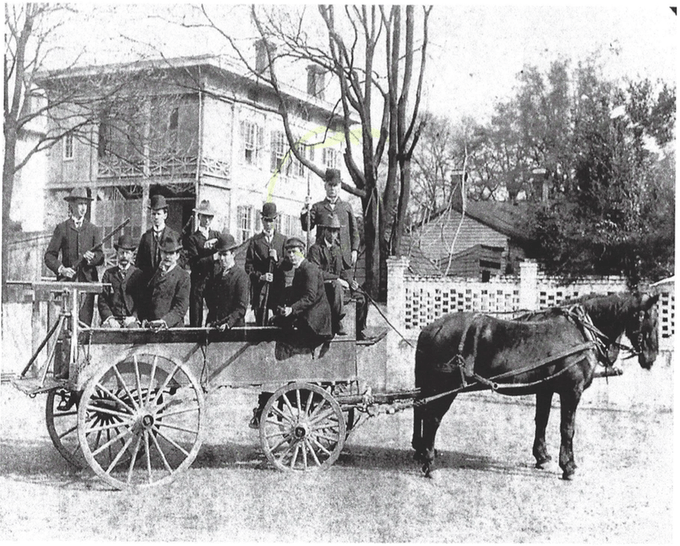

"He had the rank of Captain in this militia company," Watson says. "He was given the responsibility of commanding the machine-gun wagon. This crowd actually had bought a machine gun and installed it on the back of a horse-drawn wagon.

"And Captain Keenan commanded the group of men who drove it into action. And it is believed that they opened fire at an intersection and killed 25 people at once. It was a very well-planned military operation."

Most historians agree that at least 60 people died, but possibly hundreds. Spotty records make a specific count impossible. Hundreds more black citizens — mostly journalists and business and political leaders — fled the city. Once the white supremacists’ grasp on power was secured, they implemented the sorts of Jim Crow laws that had taken hold elsewhere in the South, disenfranchising blacks for the next 67 years.

Re-Writing History

But they didn’t just take control of the government in Wilmington. They also took control of the narrative about how they achieved it.

"It was often quite referred to as a disturbance or a race riot or some sort of incident between blacks and whites," Sturkey says. "And it had this unfortunate result but ultimately that the whites were justified, that the white leaders were justified, in the use of force. Because the black people had just gotten out of control. So that's largely how it was talked about."

There is no mention of William Rand Kenan Sr.’s role in the massacre on the memorial to him that has stood in Kenan Stadium for decades. A plaque briefly describing the history of the Kenan family refers to their having made their fortune in “oil and railroads,” but makes no mention of the family’s slave-owning past — and certainly does not mention the Wilmington Massacre.

Re-Naming Kenan Stadium

In September, I published an article about the man Kenan Stadium was named after. A week later, the UNC student newspaper, the Daily Tar Heel, followed up with a striking front page.

"It was a big aerial shot of the stadium," Sturkey says. "And it said something to the effect of: ‘William Rand Kenan Sr. was involved in an 1898 massacre that murdered 60 to 300 African-Americans. Our stadium is named after him.’ "

The coverage struck a nerve. But the question remained whether the University would do anything about it.

A few weeks before my story, protesters toppled a Confederate military monument on campus called “Silent Sam.” For years, the University had refused to address complaints about it.

Then there was the case of the building formerly known as Saunders Hall, named after Ku Klux Klan leader William Saunders.

"And it's not just that he played a role in the Klan," Sturkey says. "It's that when the building was dedicated, the Board of Trustees actually said, ‘We're dedicating this to him to honor him in large part because he played this role in the Ku Klux Klan.’ "

Saunders Hall was changed to “Carolina Hall” in 2015. That move was accompanied by a 16-year moratorium on renaming any other buildings or moving or taking down any other monuments or memorials.

And just last February, before he became aware of William Rand Kenan Sr.’s role at Wilmington, Professor Sturkey spearheaded a motion to get the plaque at the stadium — the one which mentioned the Kenans' history in “oil and railroads” — amended to acknowledge their history as slave owners. The motion was buried by the University.

"They didn't want a plaque outside the stadium that said anything about the stadium being named after people who were connected with slave money," Sturkey says.

All of which made what happened after the reports of Kenan Sr.'s role in the Wilmington Massacre pretty surprising.

"I said to myself and maybe to a friend, ‘They better change that stadium to Kenan Jr. right away,’ " Watson recalls. "And it turned out that's exactly what they did."

"Yeah, boy, lightning speed. They decided to go ahead and address that," Sturkey says.

Two weeks after my story was published, UNC Chancellor Carol Folt released a statement announcing that the plaques memorializing William Rand Kenan Sr. would be changed. They would remove “honorific reference” to him and instead focus on his son, William Rand Kenan Jr., to “tell the full and complete history.”

Whether that will be merely “the full and complete history” of William Rand Kenan Jr. — with the Kenan family’s sordid history whitewashed — is unclear. But Professor Sturkey has an idea about what he’d like to see happen.

"I would go through a complete reevaluation of every single building name," he says. "And I'm not sure that I would change the building names. I'm not sure that I would've taken the plaque off of Kenan Stadium, honestly."

Rather than remove the old names, which some critics characterize as “erasing history,” Professor Sturkey wants to do the opposite.

"I would definitely add another plaque on the side of the stadium," Sturkey says. "I would explain why we had the first plaque. I would explain why we got the second plaque. And then I would probably add another one that just listed the people that the Kenan family owned.

"And the thing is, that's a bit more uncomfortable than just changing a name, obviously. And it's just something that a lot of people don't want to be confronted with in their daily lives. But, of course, I'm an African-American historian walking around the campus. I see the ghosts everywhere."

For more on the the events of Nov. 10, 1898, check out LeRae Umfleet's book "A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot."

This segment aired on November 10, 2018.