Advertisement

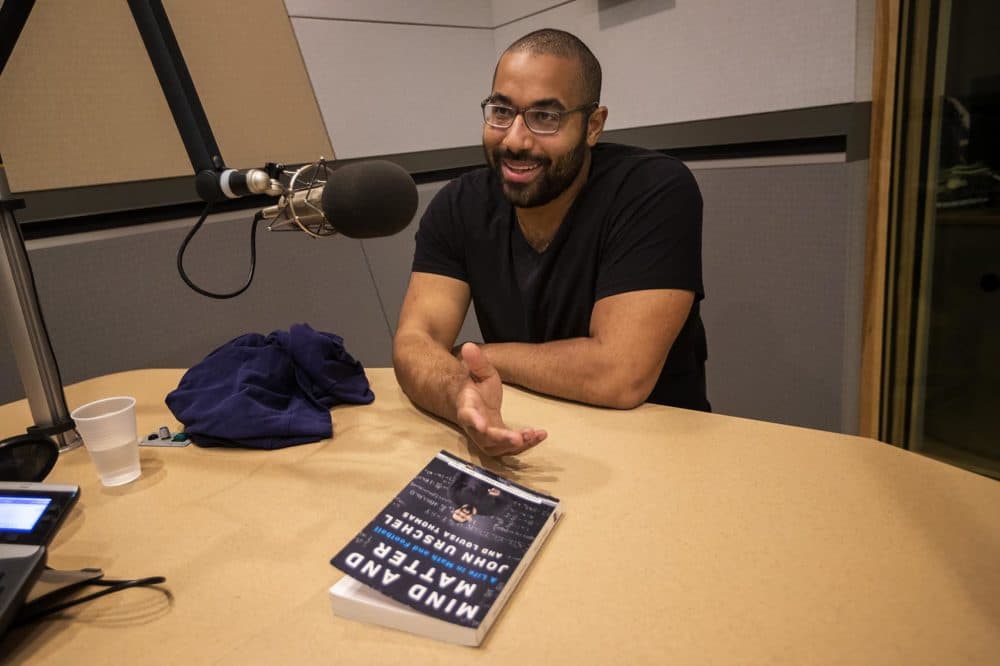

MIT's John Urschel On The NFL, Concussions And Settlers Of Catan

Resume

John Urschel watched the first round of the 2014 NFL Draft like a fan — he knew his name wouldn’t be called on the first day. But he says, he was almost certainly going to be drafted.

"In fact, I was projected to be like a third-, fourth-round pick," Urschel says.

Urschel waited all day the next day. No call. By the third day of the draft, he was starting to get nervous.

"You get concerned when Mel Kiper has you on a short list of best available for, like, pick after pick after pick," Urschel says.

When the call finally came in the fifth round, Urschel and his mom were playing a board game called Settlers of Catan. The game is a favorite of geeks everywhere.

"It is — it is a good game, but I will say you can get geekier," Urschel says. "Like, Settlers of Catan — that's just a gateway game. Like, for instance, if you love co-op games, Forbidden Desert — tons of fun. If you like being competitive, Splendor is a game that I quite enjoy. If you like sort of these mafia-type games, Coup is quite a nice sort of simple game."

I’m not sure what I expected when I sat down to interview the guy who had left the NFL to finish his doctorate in mathematics at MIT. But I’m pretty sure it wasn’t a list of board game recommendations.

But for John Urschel, games have been part of his life since he was young.

"Most kids get their allowance by, you know, mowing the lawn — things like this," Urschel says. "My mom, because she recognized that I was strong in math, wanted to encourage me with respect to math."

It started simply enough. Whenever Urschel and his mom were out shopping, she’d ask him to calculate how much change she’d be getting back. If he could do the math before the cashier handed his mom the money, he’d get to keep the change.

"And this was a fantastic game," Urschel says. "I love this game."

But soon, Urschel’s mom realized she was losing more money than she could afford to lose. So she made the game harder. Now, Urschel would have to add up all the prices and calculate the total … after tax.

Sounds difficult, right?

"But here’s the thing," he says. "Imagine how good you would be, if that was how you got your allowance."

“In hindsight, I had way more natural ability in math than football. Way more ability.”

John Urschel

While Urschel’s mom was encouraging him to focus on math, his father was providing a different sort of motivation.

"My father played football," Urschel says. "He played at the University of Alberta. I just really idolized him, and I really wanted to be just like him."

Urschel’s dad had played football while in medical school. His mom was a lawyer. But, when he was a kid, Urschel hated school. He was counting the days until he could play football.

Urschel was too big to play Pop Warner — youth football has weight limits to try to keep kids safe. So he showed up for the first day of his high school’s freshman practice having never been in a football locker room.

"Everyone's putting on their pads, and I have no clue what goes where," Urschel says. "No clue. Like, looking back on it now, I'm fairly certain I put on my pads wrong. I'm, like, almost certain that I did not put these on correctly."

But once Urschel got out on the field, there was one thing he knew how to do — almost instinctively: he knew how to hit.

"So the next day, they bumped me up to JV," Urschel says. "They said, ‘Wow. This kid has no clue how to play football. But he's really good at hitting.’ "

A College Career

Four years later, John Urschel was weighing his options for the next chapter in his football career.

"I was very uncertain of where I was going to go," Urschel says. "I thought I was going to go play football at Princeton — which my mom was sufficiently pleased with. Then, I got some interest from the University of Buffalo. Their academics are not quite as strong as Princeton's, but they have a better football team. And so my father advised me to go to the University of Buffalo for the better football, and my mother was completely opposed."

A better option didn’t present itself until December of Urschel’s senior year, months after all the top recruits had signed. That’s when Urschel was pulled out of class to meet with a coach for Penn State.

"When my mom found out that I was taken out of class to talk to a coach for Penn State football, she was livid," he says.

Urschel was Penn State’s second-to-last recruit that season. He traveled to State College to accept the offer. That’s where he nervously approached longtime coach Joe Paterno for the first time.

"He told me that I was the type of kid that they loved having at Penn State," Urschel says. "He said they loved having smart, good kids who love football and are good people. And he says, ‘Urschel, you're going to be a captain one day.’

"I'm the 25th of, like, 26 people they take. Like, I am the bottom of the bottom. And he tells me this. And what do you know?"

John Urschel was named a team captain in 2013, his senior year. But Joe Paterno wasn’t around to see it. He had been dismissed by the university in November 2011, after former Penn State assistant coach Jerry Sandusky was charged with child sex abuse. Paterno died two months later.

In 2012, the NCAA imposed unprecedented sanctions against the Penn State football program — fining the school, banning the team from postseason play and reducing scholarships. Urschel says what happened to Penn State football pales in comparison to the horrific injustices done to Sandusky’s victims.

But he’s also aware of something else. If Penn State had been under sanctions when he was recruited, the school would not have had a scholarship to offer him. And if he hadn’t got to Penn State, he says, he might never have discovered something really important about himself.

Natural Ability

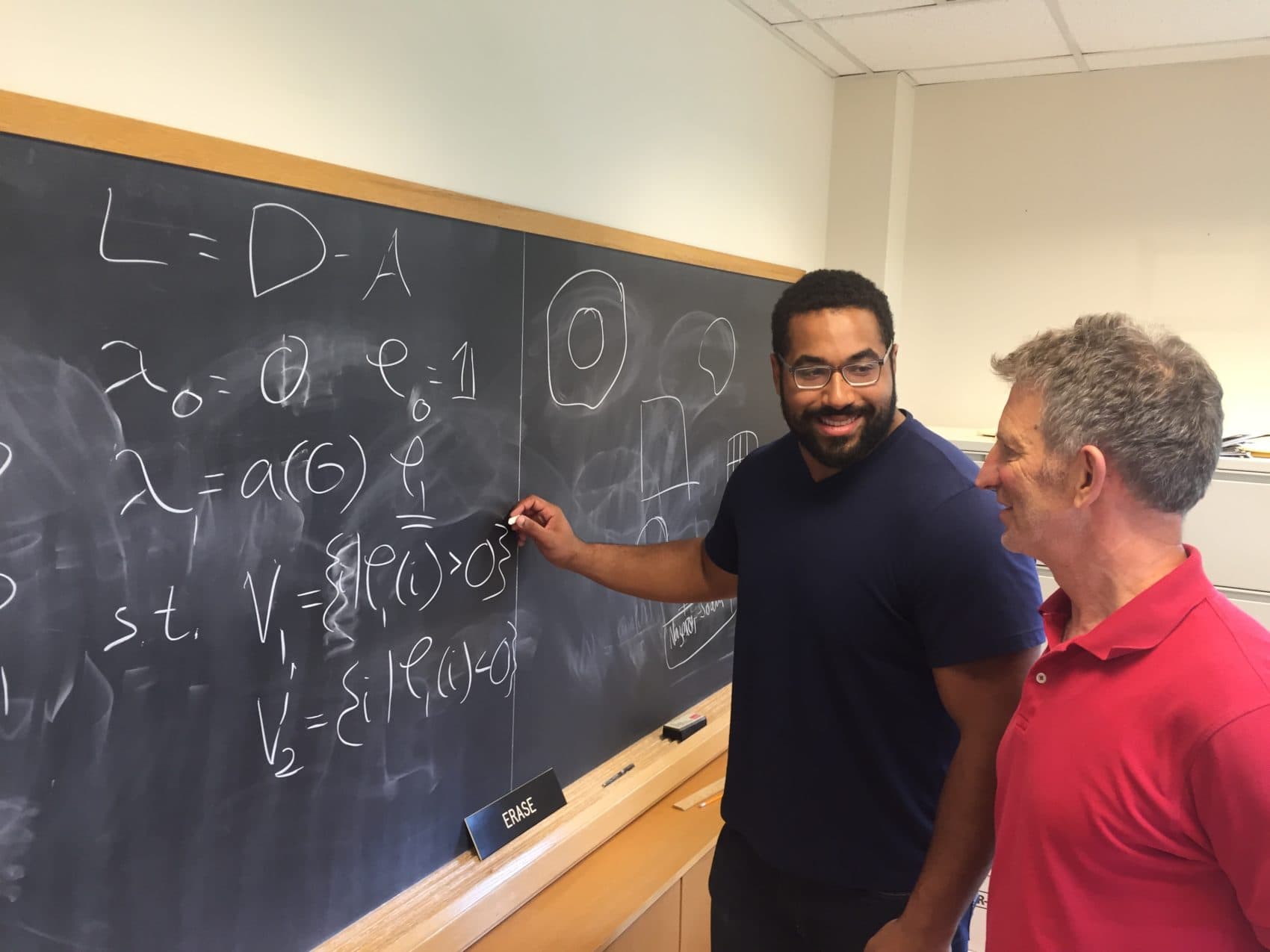

Urschel had always been smart. But he’d never really cared about academics. That changed at Penn State. One day, freshman year, Urschel was in class, listening to a lecture on differential equations.

"In order to, sort of, find the solution to one, you often need to solve some polynomial equation," Urschel says.

If you must know, it was a fifth-order polynomial equation. There’s no formal method to always compute this sort of thing. So when the instructor asked the class for the roots of the equation, he didn’t expect an answer.

But Urschel didn’t know this was something he wasn’t supposed to be able to do. So, to his instructor’s surprise, he answered the question.

He left class that day with a new thought.

" ‘Hey, you know, maybe I'm not bad at this. Maybe I have some natural ability in math,’ " Urschel remembers thinking. "People had always told me I had natural ability in football. In hindsight, I had way more natural ability in math than football. Way more ability."

By the end of his junior season, Urschel had completed his bachelor’s in engineering and started a master’s in mathematics.

He’d also been named a first-team All-Big 10 offensive lineman, and there was a lot of buzz around his future in football. One day, the offensive line coach called Urschel into his office to encourage him to wait another year before declaring for the NFL Draft. But that conversation wasn't necessary.

"The NFL hadn't even entered into my mind," Urschel says. "At this point, I'm just really enjoying football, and I'm really enjoying playing with my teammates. And I have one more year to play at this university I love with all of my best friends. And I was just so excited."

So, Urschel came back for his senior year. He stayed until he was taken in the fifth round of the 2014 NFL Draft by the Baltimore Ravens.

That’s when people really started asking him, ‘Aren’t you worried about your brain?’

"I almost never got these questions," Urschel says. "But then, slowly but surely, they started, like, picking up more and more and more. In part, probably, because I was getting more attention. In part because concussions were getting more attention. I mean, I think our trajectories of attention, we paralleled each other a little bit."

Priorities

Urschel had one diagnosed concussion in high school. It wasn’t football-related. His second concussion came during training camp in his second year with the Ravens.

"I just got hit in the side of the head," Urschel says. "I got blindsided, and I got knocked out."

Ever since he was a kid playing games with his mom, Urschel had entertained himself with math. And he’d kept working on the academic papers he’d started at Penn State even while he was playing with Baltimore. But when he got that concussion, he found that higher-level math was suddenly out of his reach.

"It was so frustrating," Urschel remembers. "My brain is not going. Like, I'm just not capable of processing these things. It was like — I was not someone you wanted to be around, because I was so angry and frustrated."

Urschel says not being able to do math was harder than not being able to go to practice.

"But I have to say, the not being able to play football — this was also like upsetting and frustrating to me," he says. "So I was, sort of — I was just quite displeased."

As Urschel continued in his pro career, the questions kept coming: What about concussions? What about brain injuries? What about your future?

What did Urschel make of all that?

"I ignore it. I really, sort of, decide, ‘No, I'm not paying attention to this. I'm playing football. And whatever happens when I'm 50, 60, 70, it's gonna happen — it's gonna be fine,’ " Urschel says. "In fact, someone asked me about this like a day or two ago — about that concussion and my retirement. Like, ‘What was the relationship?’ And I didn't realize this until that person asked me that question. Absolutely nothing. I forgot about that concussion. Like, it happened. I've moved on. And I really, like, forgot about it."

John Urschel, PhD ... Almost

In January of 2016, during the NFL offseason, Urschel arrived in Cambridge to begin his doctoral studies at MIT. That's when his "what happens, happens" attitude started to change.

"My love for math just grew even more," Urschel says. "And I really thought, ‘Man, this is a career I really want to pursue. And I want to be able to do math and teach when I'm 70.’ And I found I was going to be a father. I want to be around to, like, hang out with my grandkids and things like that. People always think about that in a concussion point of view. But I, actually, I mean this in a holistic point of view. I was really glad to get out and be healthy."

These days, Urschel doesn't ever find himself sitting at MIT and wishing he were out on the field.

"No, yeah, that's not a thing," he says.

After starting in 13 games over three seasons with the Baltimore Ravens, John Urschel left the NFL in 2017. He says he’s settled into retirement really, really well.

"Everything I do here on out, this is like gravy," Urschel says. "Although, maybe I shouldn't tell people that, like, I would just do math for free — because I will be trying to get people to hire me shortly. So, pay me a good paycheck. I'm worth money. I'm good at math, I promise."

John Urschel’s new book is called "Mind and Matter: A Life in Math and Football."

This segment aired on May 18, 2019.