Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

Housing Displacement Pressures Mount In Boston's Changing Egleston Square

Resume

Part 1 of a four-part series about affordable housing in Boston. Here are Parts 2, 3 and 4.

Alex Ponte-Capellan grew up in Lower Roxbury, near Jamaica Plain's Egleston Square, in the '90s and early 2000s.

“I would hang out here in the summer times,” he says on a walk toward Washington Street. “Especially as a Latino youth, most of my friends were in JP."

He’s watching Egleston change, with new construction going up on Washington Street — the main drag of Dominican restaurants, barbershops, auto body shops and beauty salons.

And it’s changing in other ways too.

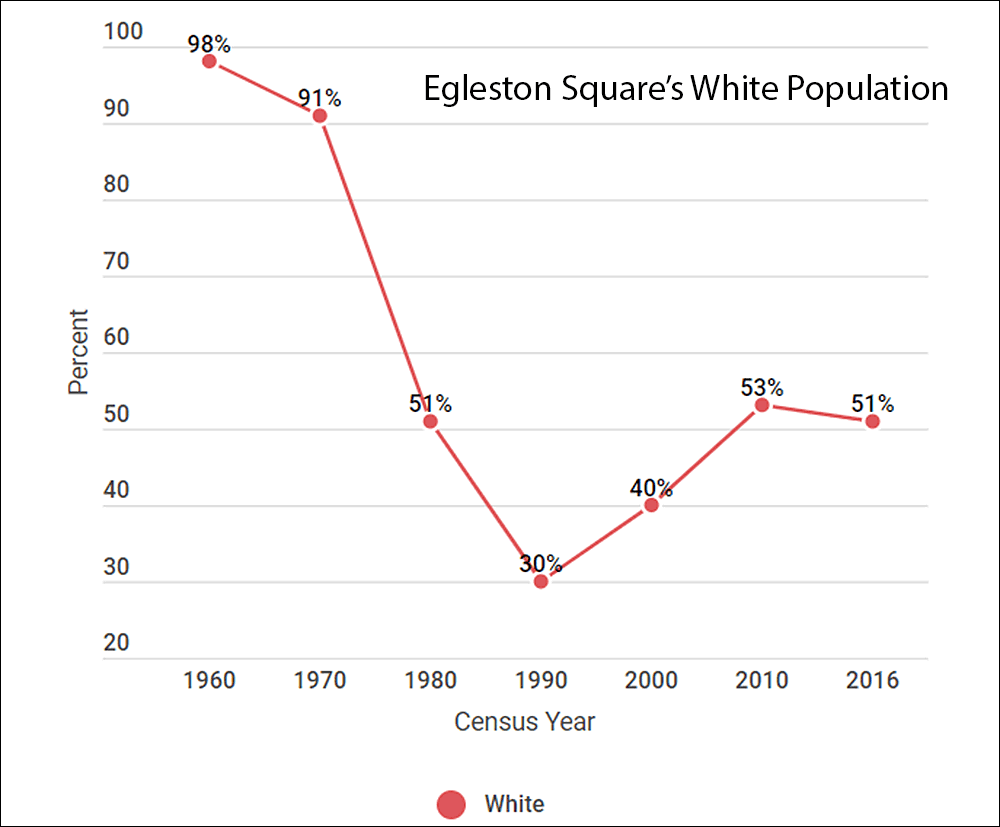

In 2010, the census tract encompassing most of Egleston flipped from majority-minority to majority white. And the median household income has increased. In 2000, it was just under $40,000; now it is almost $70,000. Thirty-five percent of households have incomes over $100,000.

“The first big sign that there was change in JP was when the Hi-Lo supermarket became Whole Foods,” Ponte-Capellan says, referring to a former Latino supermarket in nearby Hyde Square, another historically working-class area of Jamaica Plain. “That was kind of like a market signal [to investors]: ‘Hey guys, the coast is clear! Come on down!’”

Like what you're reading? You can get the latest news on housing (and other stories Boston is talking about) sent directly to your inbox with the WBUR Today newsletter. Subscribe here.

Boston is building housing, with the goal of moderating costs. But Egleston is emblematic of an intractable problem. Even as more new apartments come on the market, longtime, often low-income residents are being pushed out as displacement pressures mount in Boston's gentrifying outer neighborhoods.

A Neighborhood Once Deemed 'Risky'

Let's back up — to the 1930s.

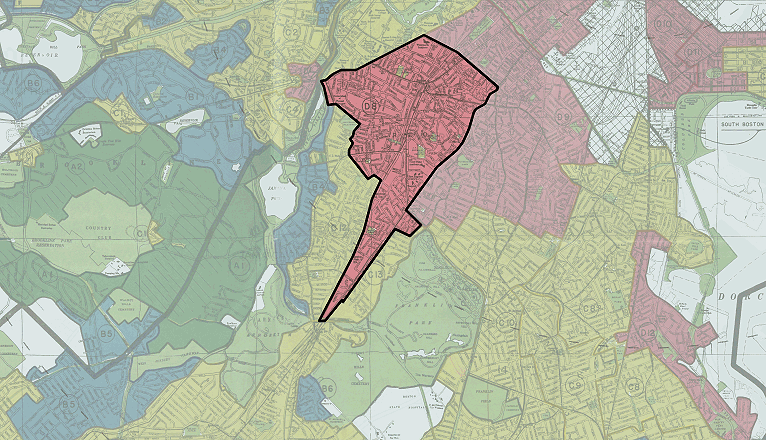

Egleston was once a “redlined” neighborhood. These areas, where people of color and immigrants usually lived, were deemed a risky investment. So, for decades, the federal government didn’t underwrite home mortgages and loans in such neighborhoods. It led to a self-fulling cycle of distressed properties and blight. In 1960, two out of every five properties in the census tract comprising most of Egleston Square were considered deteriorated or dilapidated.

By a cruel irony, the decades of disinvestment in Egleston have made it a good investment now. Inexpensive buildings are bought and flipped to cater to higher-income residents. The recent foreclosure crisis was another blow to the neighborhood, as many distressed buildings were auctioned off.

“Now we are green-lighting development and we don’t care what happens to the residents that live here,” says Ponte-Capellan, who's now a community organizer at City Life Vida Urbana, a housing justice organization in JP.

“This house, it has six apartments,” he says outside a triple-decker on School Street, near Franklin Park, that looks recently painted. “A new landlord came, bought the building, and immediately gave everybody rent increases, which most of the families couldn’t afford.”

When it was purchased, the building had significant maintenance issues. A nonprofit made an informal offer, seeking to fix it up and keep the tenants housed without significantly raising the rent. But a corporate landlord had the winning bid and made improvements, including a new roof and modern appliances. The tenants had been paying between $800 and $900 for rent. The company proposed $1,350, saying that was far below the fair market rent of $2,300. A yearlong negotiation commenced, after which the company sued. All the tenants eventually agreed to move out.

“The folks here had been negotiating for so long,” Ponte-Capellan says. “This company owns a bunch of property, they’re developing all over the place. Really, a few hundred bucks is that important for you? And because of that a few families had to deal with displacement. And some of these families broke up!”

'There Won't Be A Place Like JP'

Eric Herot, a software developer, moved to Egleston Square in 2011.

Standing on Amory Street, Herot points to an apartment near the Stony Brook T station. “My first house is the red one and orange one right there on the corner — my first JP house I should say.”

Herot says he was drawn to the neighborhood for its proximity to the Orange Line and for its diversity. He’s also watching it change.

“The neighborhood is getting a lot richer and a lot whiter," he says, "and to me, that is the kind of neighborhood change that makes me very nervous and afraid by the time I have kids, there won’t be a place like JP for them to live in."

Herot says he knows he's a gentrifier. “But the way I think about it, there’s not really anywhere you can move to that you’re not having that effect," he says. "Most people will try to live in the neighborhood that meets their housing needs, and as long as we aren’t building, you’re going to be displacing somebody in that process.”

Herot cares about displacement. For him, the only way longtime residents and new, higher-income arrivals like himself can both live in JP is if there is more housing.

Downward Filtering — Eventually

Boston neighborhoods that once had the lowest housing prices have seen them rise at a rate far greater than the rest of the city. For example, the median cost of housing in Roxbury rose 70 percent from 2010 to 2015, compared with the rest of Boston, where the median price of housing rose 36 percent.

The city's key strategy to stabilize rents is to build more housing.

Its calculations show Boston's current housing stock won’t keep up with its predicted population growth. The goal: 69,000 new housing units by 2030. Almost 16,000 of these will be income-restricted, meaning they will only be available to low- and moderate-income Bostonians.

The theory that building new housing will address affordability is called downward filtering.

The assumption is that rents are rising because there's a limited supply, and so households of all incomes are competing for the same housing. Creating new, market-rate units meets the demand from high-income households. They'll rent or buy these new apartments, freeing up the older housing stock for lower-income households.

But it's not so straightforward.

“It can take quite awhile for downward filtering to have an effect on the market,” says Chris Herbert, the managing director of Harvard’s Joint Center on Housing Studies. The predicted outcome of downward filtering can take years to unfold.

In the meantime, rents rise and plateau at a higher level.

The issue becomes how to maintain a mixed-income neighborhood while all these processes — gentrification, displacement and downward filtering — are unfolding.

“Income segregation is a powerful force,” Herbert says. “What you have to do to counter that is to take positive affirmative steps to create housing that is affordable across the spectrum, that you don’t just leave that to the market.

Basically, Herbert says, increasing the supply of market-rate units alone isn’t going to solve the housing crisis. There have to be active efforts to build and preserve affordable housing for a range of income levels.

Herbert adds that because the cost of building in Boston is so high, the cost of housing will also always be high. Indeed, the cost of construction is a key reason rents remain elevated, even as more units are getting built, and why building occurs at the higher end of the market. Reducing the cost of construction would require revamping zoning to allow larger, denser buildings, where a developer could benefit from economies of scale, among other policy changes.

3200 Washington

On a walk down Washington Street, Herot points out neighborhood staples he loves, like Designs by Rey, his go-to tailor. He worries that the store wouldn’t survive a rent increase.

Nearby, at 3200 Washington, there's a new building under construction. It stands out from its triple-decker neighbors. It has six stories and will have 73 apartments and commercial space on the ground floor. The building website describes it as “setting a contemporary attitude” for the neighborhood.

Herot supports buildings like this. He is part of a movement called YIMBY — Yes in My Backyard. It promotes higher-density buildings in neighborhoods, especially along transit lines.

“The real mission of YIMBY," he says, "is to make it instead of renovating these old, naturally affordable apartments, we have people moving into new buildings like 3200 Washington.”

3200 Washington is how Ponte-Capellan, the City Life organizer, became involved in housing issues in JP. He was part of a group that protested on the proposed site, demanding more affordable housing from the developer, and more affordable housing in the neighborhood generally, as it underwent a rezoning process.

“We were out there for a few days in tents!” he recalls. “Neighbors would honk their horns as they drove by, brought us coffee and doughnuts."

After more conversations with community groups, the developers of 3200 Washington agreed to build and set aside 18 affordable units — up from the original proposal.

When the rezoning plan, known as Plan JP/ROX, was finally agreed upon through a community process, it set a goal that 40 percent of all new housing developed on the Washington Street corridor would be for low-income residents.

The Washington Street example shows how the city attempts to leverage market forces to build and preserve affordable housing. It does this by requiring developers of most new residential buildings to build affordable units on- or off-site, or by paying into a city fund. (This series will also cover what "affordable" means.)

It's one part of a two-pronged housing affordability strategy. The other is helping at-risk tenants stay in their homes. The city is seeking legislation that would strengthen tenant protections, like guaranteeing a lawyer for low-income tenants facing eviction and limiting rent increases for elderly tenants.

This article was originally published on February 19, 2019.

This segment aired on February 19, 2019.