Advertisement

Commentary

It's Time To Retire The Offensive Design Of The Mass. Flag And Seal

The overdue discussion about inequities crippling and killing Americans of color shouldn’t overlook the discrimination faced by the continent’s original citizens. Native Americans drown in widespread poverty; until recently, North Dakota tribes labored under longstanding voter suppression, an outrage that just this year, mercifully, has been abandoned. (Architects of the suppression never called it that, basking instead in justifications that would persuade only those who write with crayon.)

Compared to these life-stunting scourges, criticism of the Massachusetts state seal and flag as demeaning to Native Americans admittedly seems like swatting a fly amid a swarm of murder hornets. Yet as the welcome removal of monuments to the Confederacy (and that treasonous regime’s flags from NASCAR races) attest, symbols matter as material, micro and not-so-micro aggressions. They’re mute transmitters that announce society’s values.

At least some lawmakers grasp that truth in this Black Lives Matter moment. A state Senate committee gave thumb’s up on a bill authorizing study of a redesign of the flag and seal and passed it along to the joint Senate-House Rules Committee.

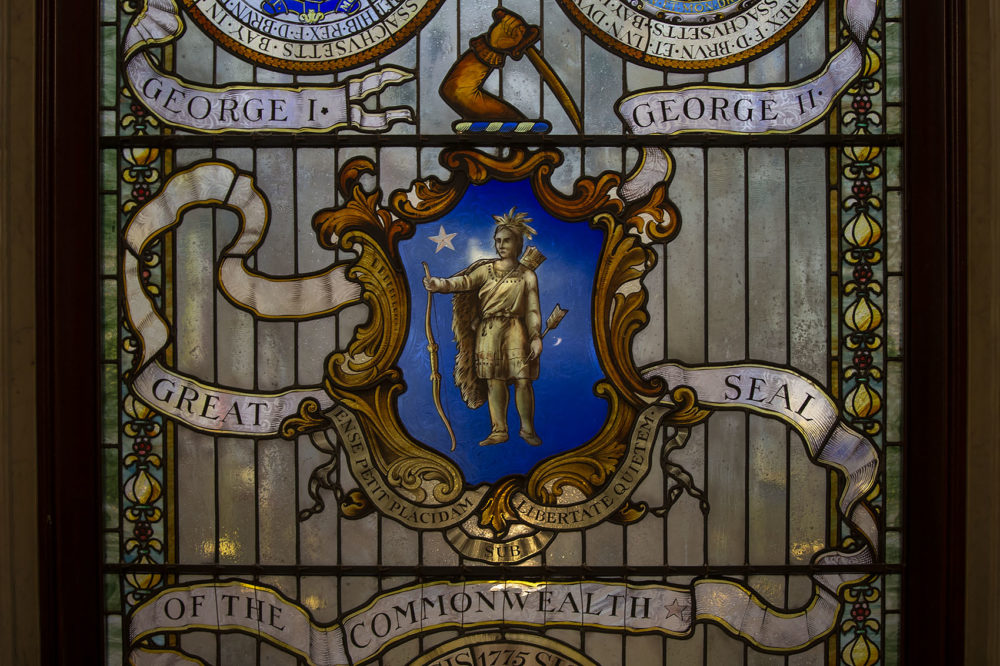

The seal — and the flag bearing it — feature a disembodied, sword-wielding arm above a Native American. The horseshoe of the state motto wraps around him in Latin, variously translated as “by the sword we seek peace, but peace under liberty” or “[she] seeks with the sword a quiet peace under liberty.”

... symbols matter as material, micro and not-so-micro aggressions. They’re mute transmitters that announce society’s values.

Native American Bay Staters have objected for decades to the design, saying it bespeaks the violent subjugation of their people, beginning with European colonizers and ravaging the arc of Native history through the Trail of Tears, the Plains Wars and Wounded Knee.

That some say the arm in question belongs to Myles Standish doesn’t make things better, his documented brutality against Natives having appalled even fellow Pilgrims.

There is a reasonable — though to me unconvincing — case for keeping the current design. Heraldry experts say the sword isn’t referring to conquest of the Natives but to the motto; together, the two of them refer to preserving liberty against the oppressive environment the Pilgrims had fled in England.

Normally, I’m all for people educating themselves when their offense is based on misunderstanding. But the seal and flag aren’t like books or articles, which can be evaluated in the totality of their self-explanation. Visual images are more like headlines, shorn of lengthy context; if they’re not self-explanatory, they don’t serve their purpose. Public symbols should be quickly understandable to the public, not just to a gnostic few. A sword brandished over a Native? Given our well-known mistreatment of Indigenous people, what are we who are uninitiated in heraldry supposed to think that means?

The Massachusetts legislation recognizes this. It would create a commission, including tribal members, to study features of the state seal and motto, “including those which potentially have been unwittingly harmful to or misunderstood by the citizens of the Commonwealth.”

The commission would consider a redesign, ensuring that any final seal and motto “faithfully reflect and embody the historic and contemporary commitments of the commonwealth to peace, justice, liberty and equality.”

Reforming symbols, wise heads remind us, won’t redress more substantive injustices against Native Americans — including those in Massachusetts. The state’s Mashpee Wampanoag tribe is jousting with the Trump Administration, which is trying to remove reservation status that the tribe needs to build a Taunton casino without state licensing approval. “If that happens,” Boston Globe columnist Joan Vennochi writes, “the beneficiaries would be other casino operators, including some with reported connections to President Trump.”

A sword brandished over a Native? Given our well-known mistreatment of Indigenous people, what are we who are uninitiated in heraldry supposed to think that means?

Vennochi is right that gambling is not an economic development tool that King Solomon would devise. She’s also right that the government nevertheless offers it to tribes from whom we stole sovereignty and prosperity long ago, and that meddling with that process on behalf of cronies is presidential malfeasance. So Bay State Natives have more on their plate than a new seal and flag.

But more than half a century ago, President Lyndon Johnson summed up our Indigenous people as The Forgotten American. Today, in an era when we’re asking whether offensive statues and flags belong in the public square, a seal-and-flag redesign could be the beginning of remembrance in Massachusetts.