Advertisement

Virginia museum works to uncover town's history of slavery

Resume

As recently as a couple of years ago, most people in Brownsburg, Virginia — population 33 within the village and a few thousand around it — would proudly tell you that they didn't have slavery in their history, at least the way the deep South did. And if slavery was part of the picture, residents were taught in school that enslaved people were cared for like a part of the family.

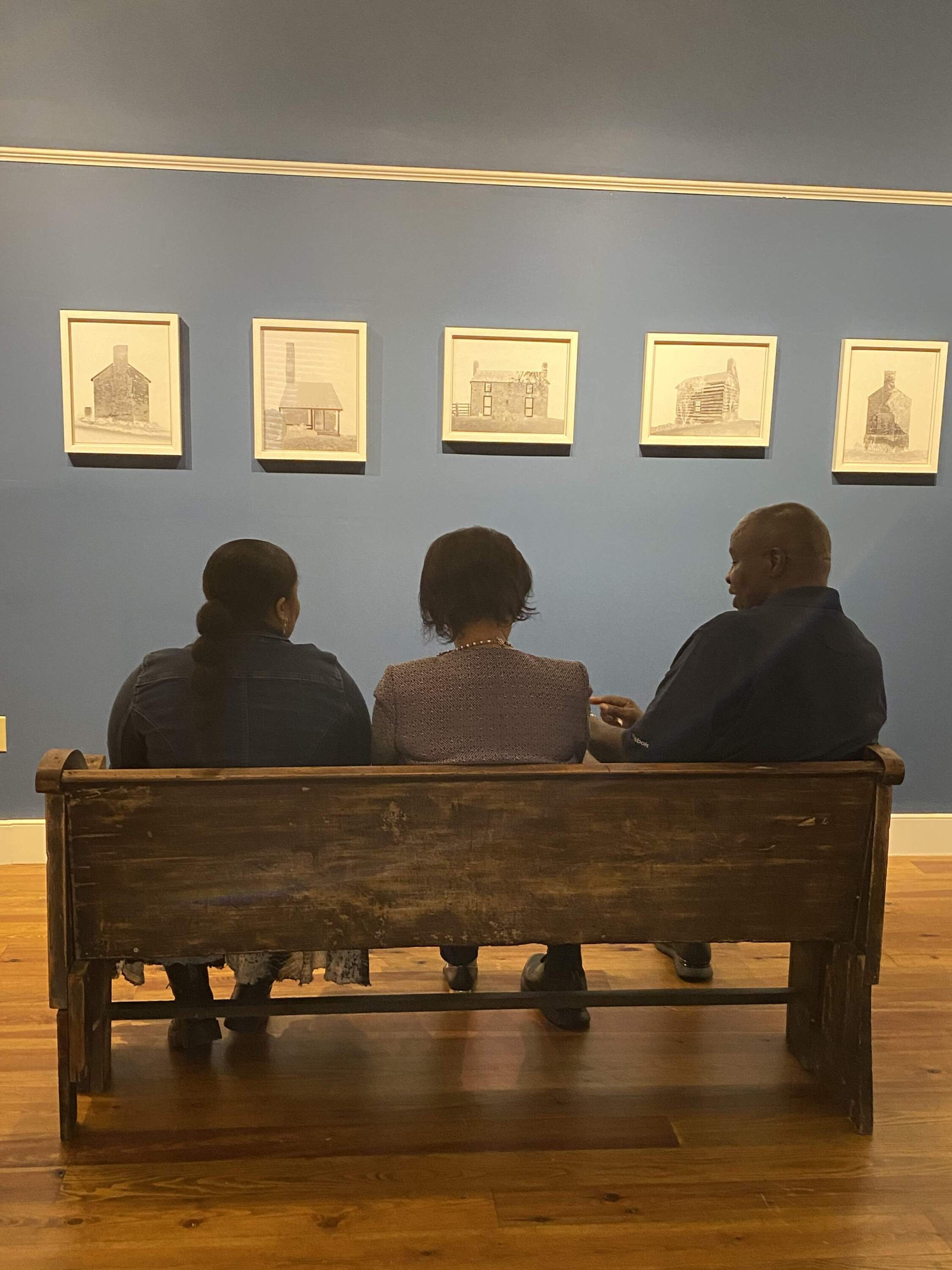

Then in 2019, architectural preservationist Jobie Hill of the Saving Slave Houses movement told the board of the Brownsburg Museum that there was a rare cluster of 5 so-called ‘standing slave houses’ in Brownsburg, probably standing because they were built of brick, although one was built of wood.

The Brownsburg Museum organized a one-day guided tour in partnership with the Historic Lexington Foundation, unsure of what to expect. Hundreds showed up, and there was a hunger to learn more. Who lived there?

But Julie Fox, volunteer Museum Committee Chair, and the small volunteer staff were all white. They knew they couldn't do an "I feel your pain" kind of exhibit, Fox says.

The volunteers first met with members of the local Black church, who gave their blessing for an exhibit. They involved graduate students and scholars from the University of Virginia who began research and interviews. Students from Rockridge County High School pored over tax records to find names, historians and local teachers. A 5-year-old girl digging in her family's yard found artifacts, but Stanley Land was key.

Born and raised in the area, Land was a star football player at the University of Virginia. His research uncovered the Haliburton family and patriarch Jacob Haliburton — Land’s ancestors — who'd been enslaved in the mid-1800s. Land and other descendants contributed insight and their words to the project, words that now live on the museum walls.

Land's family story became the backbone of the new exhibit, “Interwoven: Unearthed Stories of Slavery.” Land, his sister Betty Warren and her daughter Elizabeth walked through it for the first time, with volunteer Dee Papit, who wrote the exhibit.

For Land, seeing Haliburton's name on the wall marked the start of his great-great-grandfather's life in America.

The keeper of the family story was his grandmother Betty Haliburton, who lived to be 101 and saved all the family memorabilia, including photos that are blown up on the museum’s wall. Land says the awe-inspiring images gave him chills, especially the picture of Jacob Haliburton's son William.

Warren says when she reached out to touch her ancestor Jacob Haliburton's name, she thought about what he went through. A friend of Warren’s was shaken by the exhibit because she didn't realize that slavery happened here.

“What makes our family unique is that we learned to read and write,” Warren says. “Our ancestors passed that thriving down to their children.”

“I think it's really cool, especially because I feel like a lot of Black families can't go back as far as we can,” her daughter Elizabeth says. “It's amazing.”

Advertisement

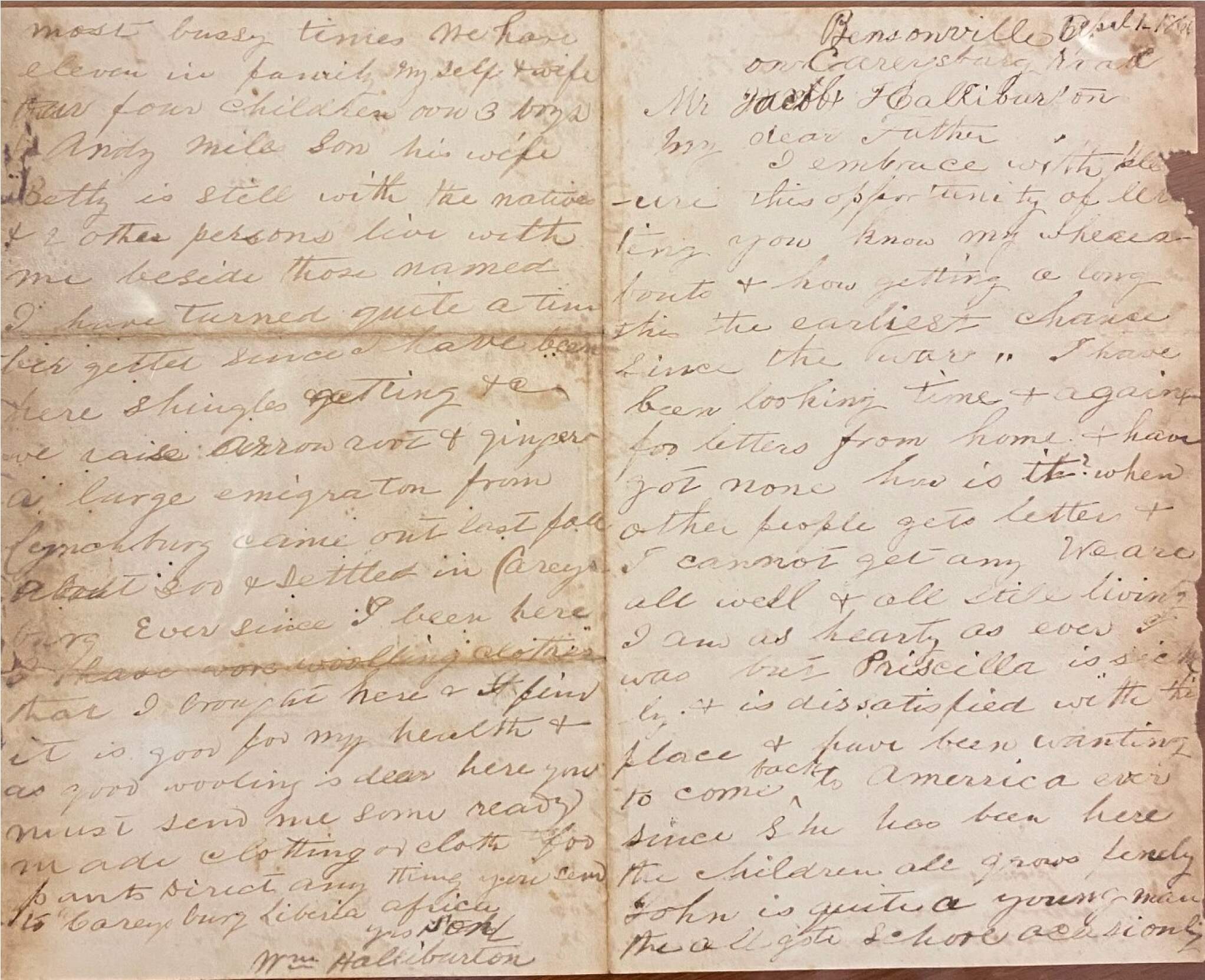

A major part of the exhibit is a letter written by William Haliburton back to his father Jacob from Liberia, a colony created to reduce the number of "freed slaves" after the Civil War. It was touted as a land of milk and honey, but it was a treacherous trip to a dangerous place.

William Haliburton took his wife and four out of five children there and wrote about heartbreaking homesickness and hardship: no farm tools, no cloth for clothing.

“You try to put yourself in his shoes and it just makes you weep,” Warren says. “Did they make it?”

The original letter is on loan from the special collections archive at Washington and Lee University. Fox unlocked the case and let Land safely touch the letter.

“That’s his handwriting,” Land says. “It just smacks you in the face.”

While he'd known the letter existed, Land had never seen the original. During a house remodel, a worker broke through the wall and a tin coffee can containing the letter fell out.

“I had a need to understand. I have three sons. I want them to know about their family history. I want their children to know about their family history,” Land says. “I want them to know this is who they are.”

Soon, other descendants joined Land and Warren in the museum, including 85-year-old Betty Brown, the longtime postmistress of Brownsburg who was once voted honorary mayor. She said she didn't know her ancestors had been enslaved here.

When asked why Black residents might not have known that, Brown says: "That's a big question. We just got along, let's just say that.”

David Green also came to the museum. He’s an associate professor of materials science and chemical engineering at the University of Virginia and a descendant of the Haliburton family, as well as another line. His fourth great-grandmother lived in one of the standing houses.

It's a pilgrimage for Green. His third great-grandfather is buried nearby.

“I come back here to show appreciation to my ancestors, really,” Green says. “Just to say thank you for giving me the opportunity to do the things that I am doing today.”

Inside the standing house, Brown says she found out two years ago that enslaved people lived there, even though her mother worked in the main house next door. She doesn't yet have the words to describe standing in this small, cramped space, with its huge fireplace, brick walls, wide wood plank floors, and wood beam ceilings that the tallest among us barely clear.

“This professor said when she came out, ‘Look around because in these small, unchanged villages like Brownsburg, history is right there,’” Fox says. “And one of the things I've experienced is that Jacob Halliburton is a person. When I go to the museum, and I'm there a lot, he is there. I can see him. And I think he must be so proud of Stan and Betty and Elizabeth. Those good genes of his, what a wonderful family they are.”

This segment aired on June 4, 2024.