Advertisement

Joni Mitchell biography 'Traveling' tracks a journey that changed popular music

Resume

Joni Mitchell — an only child born on the Canadian prairies — reinvented herself for more than six decades, aptly singing “I’m on a lonely road, and I am traveling, traveling, traveling, looking for something, what can it be?”

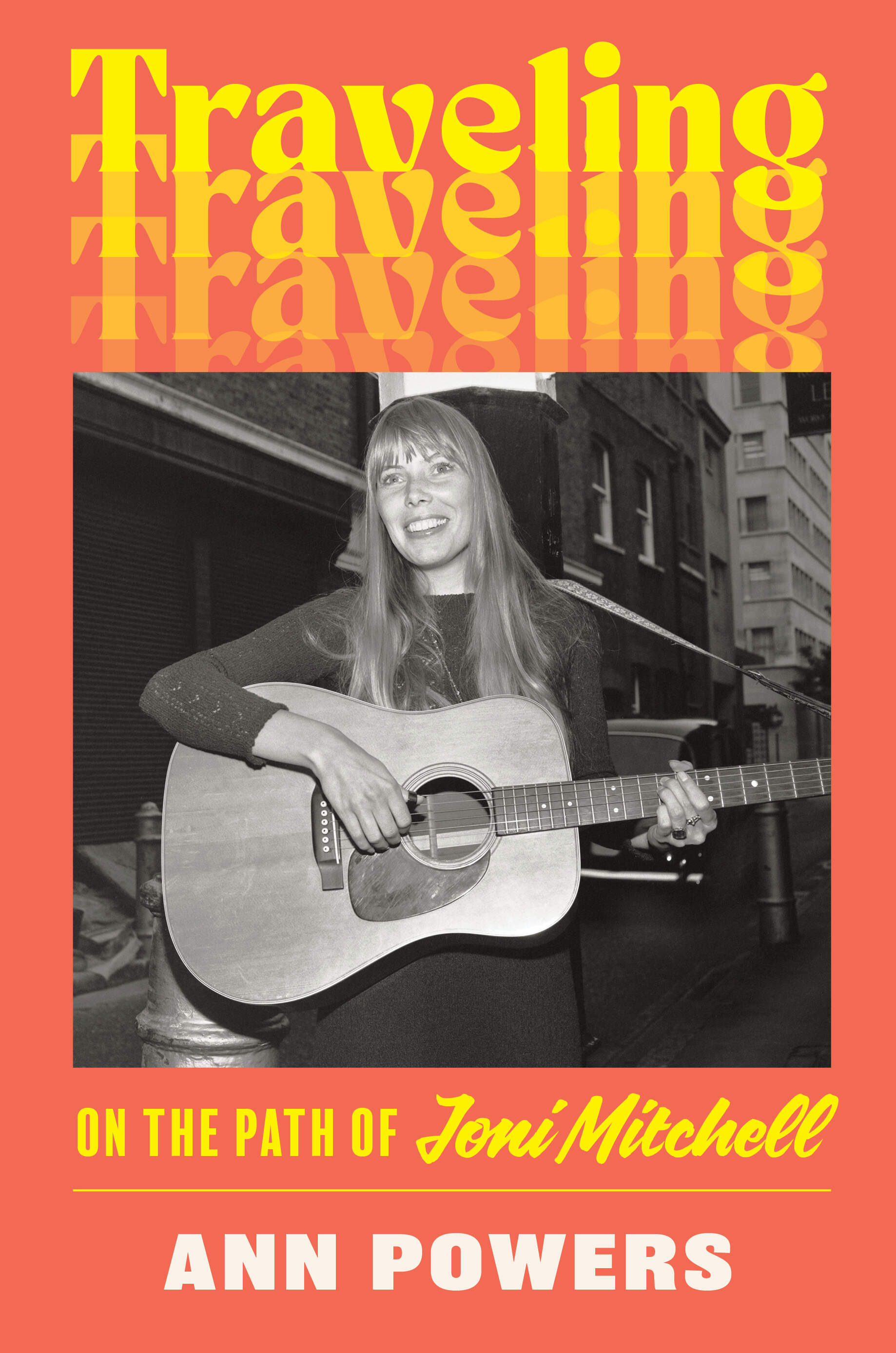

NPR music critic and author Ann Powers’ new biography, “Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell” follows her wanderings and delves deep into the influences — the people, trends and circumstances — that paved Mitchell’s longer than 60-year journey.

Mitchell struggled with polio-induced paralysis, then didn't stop moving once she could. Now 80, slowed by a rare disease and a brain aneurysm, she embodies a mother role for many woman artists.

Mitchell made her way in a man's world. While she worked the coffee houses in Canada, a Toronto music critic wrote about her high cheekbones, lustrous blonde hair, full lips and brilliant smile. “But don't let just the looks of this girl dazzle you. Listen to her,” he remarked.

“It sums up something about music writing that's kind of embarrassing to me, a lifelong music writer, which is that even when a male music writer was trying to tell people to go beyond this woman's looks, he was still salivating over her,” Powers says. “At the same time, the fact that he felt the need to say, ‘Don't just look at her, listen to her,’ she was remarkable and people recognized her as such.”

In Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon, Mitchell lived among artists like Graham Nash, Stephen Stills, Cass Elliot and Jackson Brown. Mitchell figured out how to become “one of the boys,” Powers says. The singer code-switched between masculine and feminine roles in both her life and music to form alliances with male musicians.

“Sometimes they were romantic, but oftentimes they were just as crucially creative,” Powers says. “It was that total devotion to music making and creativity and art making that drove her and caused her to carve out this space.”

Critics often hyper-focused on Mitchell’s relationships. When Rolling Stone published a chart of artists at the height of the Laurel Canyon music scene, Mitchell's name was surrounded by a lipstick mark representing her romantic partners.

“She was a studio rat. This was who she was making music with, and those musical connections are the truly important aspect of her life story,” Powers says. “And that's really what I wanted to illuminate.”

Fearing danger and reasoning that an appearance on "The Dick Cavett Show" would provide her more exposure, Mitchell’s manager didn’t want her to appear at Woodstock in 1969. Yet she wrote the song “Woodstock” — an example of Mitchell getting revenge, Powers says — after watching the iconic music festival on TV.

In 1971, Mitchell released her fourth studio album, “Blue.” In “A Case of You,” Mitchell “expresses her desire and her sensuality, not just her heartbreak,” Powers says.

“River” became “the great alternative Christmas carol” for people who feel isolated during the holidays, Powers says.

“‘River’ is an important song for me, thinking about Joni over her long career,” Powers says, “because such a huge part of Joni's story is this impulse to move on, to escape, reach a place of solitude that would be an antidote, that impulse to skate away.”

In the mid-1970s, Mitchell turned to jazz with collaborators including Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius and Charles Mingus.

During this time, Mitchell dressed in what she described as a “sleazy suit” and an afro wig, painting her face brown to portray an alter ego she called Claude, then Art Nouveau. She went to a party dressed as a Black man, which many people gave her a pass for over many years.

It was a transgressive act of appropriation, Powers says. Mitchell said many times she believed “the spirit of a Black man lives within her” and she had a right to perform it, the author says.

Advertisement

“It was a time when a lot of white musicians thought they had a right to adopt Black inflection in their singing styles, to align themselves with nonwhite artists and cultures without recognizing their own privilege. So she was hardly alone in that,” Powers says. “But at the same time, that can't be a reason for us to move on without confronting the reality that it happened.”

In the 1990s, Mitchell released two orchestral albums, “Both Sides Now” and “Travelogue.” She worked on the albums with her ex-husband Larry Klein.

“It is one of the most ingenious examples of an artist whose voice has changed over time, finding a new setting and a new way to present this more mature, more weathered voice,” Powers says. “She is the torch singer now. She is that woman in the dark cafe or the bar with Richard that we met in her song ‘Last Time I Saw Richard.’ She is that person now.”

In 2015, Mitchell survived a brain aneurysm. It took years for her to recover. But in the mid-2020s, she forged a friendship with singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile, who inspired her to get back on stage.

Mitchell always appreciated her admirers, but also pushed back against the construct of fame and what she called “the star maker machinery.”

“She is in a period in her life of gratitude and of receptiveness,” Powers says. “I always sense a gleam in Joni's eye though that she's laughing a little bit about it too.”

Karyn Miller-Medzon produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Mark Navin. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

Book excerpt: 'Traveling: On The Path of Joni Mitchell'

By Ann Powers

Throughout my time winding along Joni Mitchell’s path, her songs infiltrated my brain. They directed my emotions, faded and changed to others. “Nothing Can Be Done” is the one that stuck as I turned toward the later phases of her life. I consider it a blues, maybe not musically—the music, written by [Larry] Klein, is a minor key variation of the soft-rock “Boys of Summer”—but in the way that genre designed to carry ancient pain encompasses both complaint and a certain hard acceptance. In the song, Joni confronts her lover, who’s just grabbed his keys to head out toward something or someone she can’t be.

But she also faces her aging self as she questions her impossible longing to keep things as they were. The song captures the feeling of being on the threshold, wavering, unbalanced, knowing there’s no choice but to accept gravity’s pull. Those words: I am not old, I’m told, but I am not young. Mitchell delivers them in clipped syllables. She’s not yet sure how to settle this argument with herself. Middle age equals ambiguity, and for women it can hit at any point after fertile young adulthood wanes, graying the days before the onset of whatever illness or other calamity finally fells you. Joni Mitchell must have thought about this as she stared down solitude again at fifty.

Nothing can be done but grow older, more damaged and wiser, more accepting of life’s cruelties, Joni sings. Then she asks: must I surrender with grace the things I loved when I was younger? She’s talking about sex, at least the ridiculous fire of it, the way it dominates and opens doors and burns down houses. She also might mean her own ego—that fiery “I” that has so much power over people, making them think they can thrive dependent only on themselves. Nothing can be done, Joni murmurs, besides opening up a little to the idea of compromise, to the possibility that others might know something that you don’t immediately understand about the way the world operates, or even about how you operate, how your life and work fit into a picture bigger than yourself. To surrender with grace is to open your arms. Share access to the life you’ve made with people who care about you, and trust that what you’ve done will live beyond the border of your fierce protectiveness. Let others reinterpret what you once insisted only you could say.

This is the work of making a legacy, and Mitchell turned toward it after Turbulent Indigo won its unexpected Grammy for Best Pop Album in a category that included younger and hotter stars like Madonna and Mariah Carey. That album had already signaled a new phase, away from the ebullient experimentation of her prime Klein years and toward a more contained reckoning with imperfection in the world and her own life. She still staged protests, in songs like “Sex Kills,” about AIDS and objectification, and “Borderline,” which bemoans the racial and gender divisions afflicting America. If, as Klein and Mitchell have both said, Turbulent Indigo is about the dissolution of their marriage, she processed her pain in lyrics that reached out toward others: the abandoned mothers in “The Magdalene Laundries”; the battered women of “Not to Blame.” As for her own predicament, this was still Joni: she identified with the most fabled sufferers, the biblical Job and Vincent van Gogh, in whose image she crafted a self-portrait for the album cover. All my little landscapes and all my yellow afternoons stack up around this vacancy, she sang in the title track, dedicated to him, identifying loneliness as a source of madness, or at least its main companion.

How to move on? She still had herself, the Joni Mitchell she had created within music over more than a quarter century. The future felt uncertain, but the past was right there. And the market was hungry for it. Before turning fifty, Mitchell had stayed away from retrospectives, though Reprise issued a limited-edition one in 1971; she didn’t want to look back. But now she started to think about how to witness her life in full.

As the 1990s turned toward the new century, Mitchell continued to create, though at nowhere near her previous pace. She did start releasing compilations, her way. The autumnal decades of her life would require patience and perspective. One thing about reaching maturity is that you realize that even as the future becomes ever more unclear, you cannot really be alone as you head there: there are the people who’ve forged this road, the ones who still walk with you even if you tried to walk away from them, and the ones who follow, to whom you owe your light, that legacy. Joni recognized this as she became the matriarch she’d never exactly planned to be.

Excerpted from “Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell.” © 2024 by Ann Powers. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This segment aired on June 11, 2024.