Advertisement

Postmortem, Ep. 3: The collectors

Resume

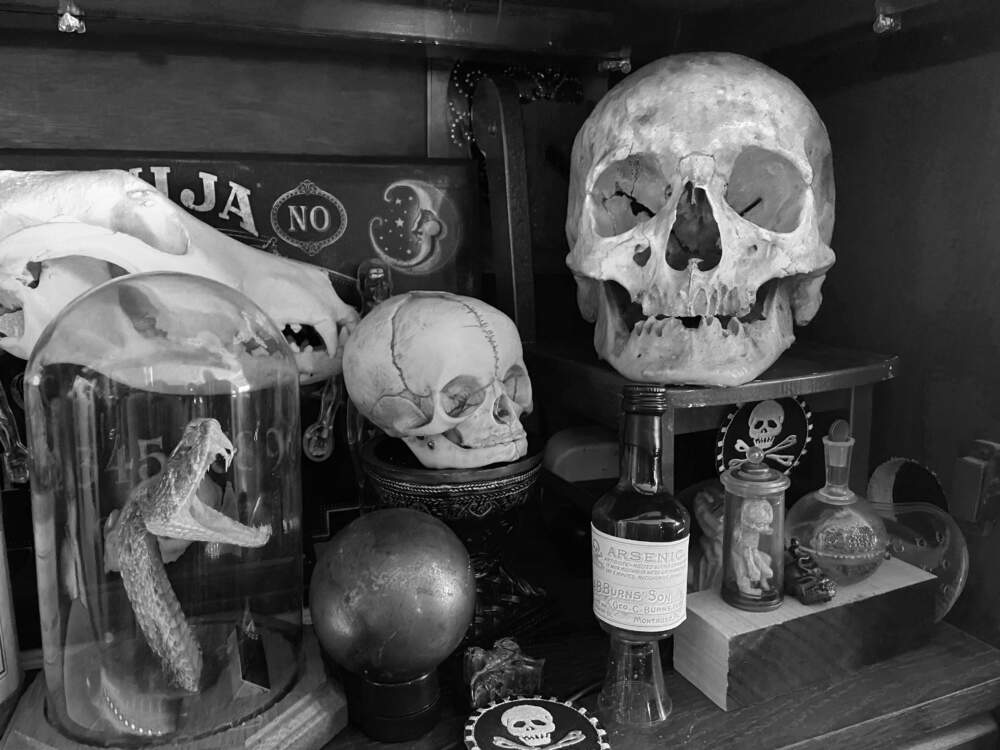

Who are the people buying this stuff anyway? People who collect human remains don’t see it as gross. In fact, these collectors connect and communicate openly on social media. In Episode 3 of Postmortem: The Stolen Bodies of Harvard, reporter Ally Jarmanning meets Jeremy Pauley, the Pennsylvania man with a tattooed eye whose arrest unravels this whole case.

Jarmanning dines in the home of a Delaware couple with a house full of skeletons; they call themselves “rescuers” of human remains.

And she introduces us to Mike Drake, a New York City collector. Through all these conversations, it becomes clear: There's no solid ethical line in this world of remains collectors; everyone is making up their own rules.

If you have questions, comments or tips about this story, you could reach us at LastSeen@wbur.org.

Transcript

Ally Jarmanning: A heads up, this episode could get graphic, at times. We're talking about dead bodies here. Take care while listening.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Oh, man. I've been in the car for a long time.

Ally Jarmanning: I'm in rural northeastern Pennsylvania, just over the New York border. I took my exit off the highway almost an hour ago and I'm still not at my destination yet. I'm passing old houses and farms and not much else.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): I thought there would be like a gas station or convenience store or something when I got off the highway so I could pee, but there is not.

Ally Jarmanning: I have a full bladder and some nerves. Because I'm on my way to knock on the door of a guy named Jeremy Pauley.

I want to talk to Jeremy Pauley, because it was his arrest that set so much in motion. The investigation into him exposed Harvard and Cedric Lodge. Without Jeremy, I'm not sure these crimes would have ever come to light. Harvard might not have had any idea what was going on.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Turning onto North Main Street.

Ally Jarmanning: This unannounced visit is a long shot. Since his arrest more than a year ago, Jeremy hasn't talked to any reporters. But I still want to try.

So that's why I'm here, five hours from Boston, driving on windy rural roads in backwoods Pennsylvania. I'm looking for a body parts buyer.

I've door knocked a lot of people as a reporter. Victims, suspects, family members of both. If they answer the door, there are different responses. Sometimes, they are furious. Yell at me to get off their property. Other times, people surprise me and invite me in.

Some seem like they want to talk but feel they shouldn't.

I wonder how Jeremy Pauley will respond.

I'm driving slowly on these country roads, looking for his house.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Oh s—, I missed my turn.

Ally Jarmanning: I take a curve and I drive right by it and have to bang a U-ey further up the road.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Or maybe I can just park in front of, yeah, I’m gonna pull up to the side.

It's a light, very light blue house. A-frame, it's got a little porch on it.

Alright, here we go.

Ally Jarmanning: I walk up to the house, microphone in one hand and a letter for him in the other, to leave in case he's not home.

The house is kind of run down and tired-looking. There's no walkway, so I just step across the grass. I make my way onto the rickety wooden porch and knock on the door.

The curtains are pulled shut so I can't see inside.

I wait and listen. Nobody comes to the door or pulls back the curtain. I decide I'll just leave my letter. But before I do, I try knocking one last time.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): I'll give one more, one more hit.

Ally Jarmanning: Nothing. I'm actually walking away when I hear the door open behind me. It's Jeremy's girlfriend.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Hey, I'm Ally. I am a reporter with the NPR station in Boston.

Sophie: We're not talking to reporters right now.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): I totally understand that…

Ally Jarmanning: I figured this was the answer I'd get. Maybe if I can get a few minutes with Jeremy, though, I can convince him to speak with me? She doubts it, but he just got home, so she'll ask him. I wait there for a few seconds. And he comes to the door. Jeremy Pauley. The guy I've read so much about.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Hi, how are you?

Jeremy Pauley: Good.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): I'm Ally. I'm a reporter with WBUR. It's the NPR station in Boston.

Ally Jarmanning: This is Postmortem: The Stolen Bodies of Harvard. I’m reporter Ally Jarmanning.

This is Episode 3: The collectors.

The story of why I'm on this doorstep in rural Pennsylvania starts nearly two years earlier.

In July 2022, police showed up at Jeremy's apartment — not the one I'm at now, but one he shared with his then-wife, about three hours away from here.

His wife had called the police there. Jeremy wasn't even living there at the time. She had gotten a restraining order against him and served him with divorce papers.

His wife went down into the basement and looked around where Jeremy kept his work. She found a few five-gallon buckets and inside: body parts. A lot of body parts. Brains, livers, skin and fat, a child's jawbone.

This was the break in the Harvard case. Except, when they found these buckets of body parts in his basement, officers had no idea they connected back to Harvard Medical School.

The details of the arrest were shocking, but not really national news.

What Jeremy would tell investigators and the connection to Harvard, we wouldn’t hear about for almost a year.

Advertisement

In this moment, police were just beginning to learn about Jeremy Pauley's pivotal role in this nationwide network of human remains trading — people buying and selling skin and bones and organs online and through the mail.

He is kind of a famous guy, at least in the online oddities circles. He's well known as a collector and dealer, and people respect him and his craft. He's big in body modification circles and does blood art which is, well, art with human blood.

Jeremy Pauley (on radio show): I always tell people, like, I was the goth kid who never grew up.

Ally Jarmanning: I found a couple of interviews he did over the last few years.

This one, on YouTube, is from a radio show called "Uncovering the Underground." Here are some parts of it.

Jeremy Pauley (on radio show): There was an old show on Nickelodeon called "Are You Afraid of the Dark?" And, there was an episode, where one character, Dr. Vink, pulls out a jar with a human hand in it. And I, it's my first memory of just being like, "Oh my god, that's so interesting."

Ally Jarmanning: Jeremy collected and sold bones and skulls, but his real interest was in what people in the oddities trade call "wet" specimens — preserved organs, tissues, skin, hearts and brains.

Jeremy Pauley (on radio show): I always had a penchant for wet, especially fetal specimens. I love them because when I look at them, I don't see a dead baby.

I especially loved like anything with a congenital anomaly. Some people see them and they feel sad, but I'm like, do you know how many lives were saved? Because, you know, somebody saved this specimen and it taught doctor after doctor, after doctor, and now, you know, this particular deformity that was once a death sentence, now that kid can grow up and be a functioning adult.

Ally Jarmanning: His explanation sounds almost noble, right?

These fetuses in jars served a higher purpose. They're marking the forward march of medicine.

But that's not all.

On the show, Jeremy talked about another interest of his: the craft of binding books in human skin.

Jeremy Pauley (on radio show): I had seen a modern binding done and I was always fascinated, you know, by anthropodermic bibliopegy.

Ally Jarmanning: Jeremy told the host that he quote, "got ahold" of some human leather, and bound his first books. He was hooked. He searched for more skin, finding a jar of human tissue he says was left over from a doctor's collection.

Jeremy Pauley (on radio show): Then I just kind of started hunting harder, calling up all kinds of places that I deal with, and, you know, if you see anything like this in storage, you know, call me. I have, like, big dry spells, obviously, because it's not, like, it's easy to come by. So, I do a lot of work trying to track it down.

Ally Jarmanning: This, at least, is the story Jeremy gave publicly. But I know, from court records, that by January 2022, when this interview was released, Jeremy had a much steadier supplier.

Three months before this interview, Jeremy got a message online from a woman in Arkansas: "I follow your page and work and LOVE it.”

She explained she worked at a mortuary, and they cremate donor bodies from a medical school there.

“Just out of curiosity, would you know anyone in the market for a fully intact embalmed brain?"

Turns out, Jeremy was. They agreed on a deal of $1,200 for two brains with skull caps and a human heart.

That began a fruitful business relationship. The orders came quick. I'll read you some of the invoices she sent verbatim. They're all detailed in court records. And — warning — they're graphic.

"Seven huge pieces of skin, two large pieces of skin with tiddy, four brains one with skull cap, one lung, one penis, two testicles, and 3 hearts" — $2,000.

"Half a brain, two smokers lungs, one lower chunk of pubic skin with peen and sack attached, two larger pieces of skin, one small piece with nip" — $850.

The donor bodies would come in from the medical school for cremation, and the mortuary worker would message Jeremy to let him know the haul. Over a seven-month period, he paid her more than $10,000 for stolen donor bodies.

And then there were the fetuses.

In February 2022, a woman in Arkansas gave birth to a stillborn baby boy. She named him Lux. She wanted to have him cremated.

Lux ended up at the mortuary. As soon as he arrived, Jeremy's supplier jumped to message him. She sold Lux to Jeremy for $300. A deal because, as she said, "he's not in great shape."

Jeremy later offloaded Lux to a guy in Minnesota in exchange for $1,550 and five human skulls.

Lux's mother got the ashes of someone. Or something. Not her baby.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Oh hey, puppy.

Ally Jarmanning: I'm thinking about all of this as I look up at Jeremy standing just inside his house.

I am doing something about the Harvard story and I know you probably cannot talk at all about what's going on, but I didn't know if you'd be willing to talk just a little bit about your work in the oddities trade, your interests in all this, like kind of how you got into this.

Jeremy Pauley: If you want to reach out to my attorney, I have him vet everything and all that. I can give you his number.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Yeah, that'd be great. Yeah.

Ally Jarmanning: He pulls out his phone to get the number of his attorney. And while he does that, I'm able to look at him more closely.

There's a lot to take in, and I try to look without overtly staring. The entire right side of his face is tattooed. It looks like it's been colored in with blue marker, the design is so dense.

And his right eye, it's tattooed too.

There's no white around the iris, just a deep, deep black. A dark abyss in his eye socket. I keep trying to look him in the eyes, but I don't want him to think I'm staring.

His head is shaved, and short, dull metal spikes are embedded in his scalp. In some photos I've seen of him, he has a silver grille on his teeth with fangs, although I don't see that today.

Almost every news story about the thefts at Harvard includes his mug shot. Or photos from his social media pages, him grinning with those silver teeth looking exactly like the kind of guy you'd guess deals in human body parts.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Um, yeah, I just — you know, you've kind of made the face of all this. And it just, you know, reading through the court documents, it's doesn't seem like you had any direct connection with Harvard?

Jeremy Pauley: Yeah, they like to, they like to use my face a lot. Yeah.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): And do you, why do you think that is?

Jeremy Pauley: I mean. I'm clickbait.

Ally Jarmanning: He gestures at his face to make the point. As if to say, "duh, don't you see me?"

There's some irony to his face being associated with every news story about Harvard. Jeremy didn't even have any direct contact with the Harvard morgue or its manager, Cedric Lodge. At least according to the court documents and police records I've reviewed. But he bought remains and traded skin with people who did buy remains sourced from Harvard and from Cedric Lodge.

He faced conspiracy and interstate transport of stolen goods charges, just like Cedric Lodge and the rest of the buyers. The Arkansas mortuary worker was charged, too.

At the point I'm talking to him, Jeremy has already pleaded guilty to the federal charges. He's awaiting sentencing. But that doesn't make him any more eager to talk to me. He keeps bringing up his lawyer.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Some of the work I'm doing is talking to like a lot of people in the oddities field. So many people are asking, like, who are the people that are into this? I think most people are just grossed out by it right away.

Jeremy Pauley: Yeah, I mean, it's a niche field in general, like, as a collector or a preservation artist or anything like that.

And it's about education, so like, I'm not opposed to doing an interview of that, you know, uh, realm.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): I mean, I'm just curious, like, how did you get into all of this?

Jeremy Pauley: Like I said, I won't talk more until, you know, Jonathan clears things.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): OK. All right.

Jeremy Pauley: But, like I said, I'm not opposed to it. I'm not shooting you down. I'm not against it. I think like bringing more attention to the not scary side of all this is important, you know so like, there's a chance.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Have you said yes to anybody?

Jeremy Pauley: No.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): No? How come?

Jeremy Pauley: The media's put a bad taste in my mouth for obvious reasons. You know, like, I'm just trying to get all this done, you know? So, like, I'm just, I'm not out there to try to get famous. I'm not out there to try to, like, talk to a thousand reporters. I'm not. I'm just trying to, like, keep on with my life right now.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Totally. I appreciate it and sorry to burst into your house.

Jeremy Pauley: It's OK.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): So, I appreciate it. Thank you. Nice to meet you.

Jeremy Pauley: Thank you.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): That was more than I thought I was going to get. He actually seems like a very nice guy. And less shocking-looking in person. Like, I think the tattooed eyeball was probably the hardest thing to look at.

Ally Jarmanning: All in all, Jeremy was one of the nicer people I've ever door-knocked.

I reach out to his lawyer, who says he'll check with Jeremy, but I never hear back. Jeremy doesn't respond to messages I send him later directly, either.

Since I made that visit back in November, Jeremy pleaded guilty to more charges against him — state charges, abuse of a corpse. He was sentenced to two years probation for that.

So, Jeremy won't talk to me about his work in the oddities field or explain his interest in what he called the "niche field" of human remains. And I still have a lot of questions. How does someone get into collecting dead people? Where do they buy this stuff? And how do they think about the people these remains used to be?

After the break, I wander into a living room full of skeletons.

Ally Jarmanning: I actually couldn't believe how easy it was to find human remains collectors to talk to. I logged onto Facebook and searched well, "skulls." And I found a bunch of Facebook groups specializing in the oddities trade. I joined a public group called, "Real Human Skulls Only. No Scammer."

Despite the name, there are a lot of scammers in this group. People post stolen photos and try to get some cash.

Some of these posts, it looks like they dug up a grave and snapped a photo of the bones to sell. The skulls are cracked and looked dirty. They don't have any hardware that a medical specimen would have.

There are also more legit listings, too.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): So like this one says, vintage medical grade, partial human noggin. $450 plus, and then a picture of a little ship, so plus shipping.

Ally Jarmanning: Some of the listings spell human H-O-O-M-A-N to avoid getting flagged. And instead of using numbers to list the price, they include emojis of the figures.

I joined another group, this one called: "The Serious Wet Specimen Collectors, Buyers and Sellers Group." This page is filled with jars of preserved organs, animals, reptiles. There are dead puppies and kittens in jars, a ball python with no eyes in a jar, a six-inch sea slug in a jar.

There are human specimens, too.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): "Human wet specimen of a child's tongue, windpipe, heart, and lungs who passed away tragically from choking on a marble. The marble is still inside the windpipe. Beautiful piece borne out of a heartbreaking accident. Let me know if you are interested." Jesus.

Ally Jarmanning: I keep scrolling and one photo stops me in my tracks.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Picture is a gloved — a latex glove hand holding this, you know, tiny, little fetus.

They're just holding it in the, not even the palm of their hand, the fingers of their hand. And you can see the intestines coming out, and the fingers, and the face.

Where do you even get this?

Ally Jarmanning: The description says the fetus is about 15 weeks and had a condition called gastroschisis, where the intestines protrude from the abdomen. It's listed for $2,200 plus shipping.

It's not the last fetal remains I'll see on this reporting journey.

All my clicking around leads me to a page for something called "The Ossuary." The description says, "We ensure a safe home and dignified transition for prior medical specimens and cremains."

I reach out to the couple that runs it, Justin Capps and Sonya Cobb, and they are more than happy for me to come visit them at their home in Smyrna, Delaware.

Justin and Sonya don't have any connection to the thefts at Harvard. But I want to talk to them, and those like them, because they're part of the demand for human remains. And that demand causes people like, Cedric Lodge, to allegedly find the supply. So, I want to understand why they do this and how.

It's dark when I arrive. I'm meeting Justin and Sonya at dinnertime. They're night shifters — Sonya works in long-term care as a nurse, Justin is an ordained minister and he keeps Sonya's hours. So I'm catching them at the beginning of their day. Their neighborhood of newish single family homes and duplexes is tucked away off a busy road. I spot their house.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): His car's license plate says SKULLS.

Ally Jarmanning: Other than the license plate, the house looks pretty typical in this little subdivision. Until I step inside.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Wow. Right away. You can't miss it.

My eyes immediately drift to under the TV, where a skeleton rests on its back in a glass box, glowing under blacklight.

Across the room, next to the overstuffed leather couch, another skeleton hangs in an upright coffin. A spinal column lamp sits on a table. And I haven't even turned to my left and my right yet, where two pairs of skeletons flank the front hall.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): This is not really a living room anymore. It's been turned over to the skeletons.

Justin Capps: Pretty much. Yeah.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Standing here. I count one, two, three, four, five, six full skeletons?

Justin Capps: My coffin table.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Oh, wow.

Ally Jarmanning: Justin lifts the lid of the coffee — I mean, coffin — table to reveal the seventh skeleton in the room.

Sonya Cobb: So this was an antique coffin.

Justin Capps: 1860s.

Sonya Cobb: Um, that we sent to the Smyrna prison because they have a wood shop department and they redid this and put the legs on it and made it into a coffin table for us.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): And this was the coffin that the skeleton came in?

Justin Capps: Yeah, it was stored in this.

Sonya Cobb: Yes, that was the deal with the coffin or the skeletons when they came. They were all stored in antique coffins. And they all had to go with antique coffins.

Ally Jarmanning: Justin and Sonya don't have all these remains as a gag or so, they can live in some kind of haunted house. And they don't see themselves as "collectors" at all.

Justin Capps: Hate saying that we collect remains, even though we collect in the sense that we gather and not that we collect because we're morbidly, you know, want to have a house full of bones.

I didn't wake up and go, you know what? I think bones are something I want to play with. This was something I was called to do.

People rescue puppies and kittens, and we rescue medical specimens. These items, people, they were lost to time. For whatever reason, no longer being used, collecting dust in storage. I got one over there that's been chewed on by mice so bad she's fallen apart. And they deserve better than that.

Ally Jarmanning: This journey all started with Tyler.

Justin Capps: He's a geriatric skull. He has one tooth.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Oh, yeah. One little molar.

Sonya Cobb: That's why I fell in love with him. He was geriatric. I worked in the hospice. It was perfect.

Ally Jarmanning: They found Tyler in an oddities shop they often visited. He wasn't for sale. He was just decoration.

Sonya Cobb: He was smiling at me. I don't know what it was.

Justin Capps: He looks happy, doesn't he?

Sonya Cobb: He looked happy.

Ally Jarmanning: When COVID hit, and the store closed, Justin wanted to help out the owner and offered a loan of $1,200. He took Tyler as collateral. The owner never paid back the loan. And Tyler sparked something for Justin and Sonya.

Sonya Cobb: He got Tyler for me. And then I said I needed a whole skeleton for the corner.

Ally Jarmanning: From there, Justin got to work, looking for how to get Sonya her skeleton. Websites like Skulls Unlimited sell human skeletons for upwards of 7,200 bucks.

But Justin and Sonya didn't believe buying a human was morally right.

Justin Capps: These are former people. These were someone's parents, someone's children, brothers, sisters. They need a little bit more respect than they're given.

Ally Jarmanning: Justin kept hunting. And he found a fraternal organization — he won't say which one — that was looking to offload skeletons they'd been using for rituals.

And that’s how Justin and Sonya ended up with seven skeletons in their living room ... and more if they can find more space.

Their goal, eventually, is to open a real ossuary — a building filled with human bones. They're thinking a church, where people could visit and maybe get married and see the final resting place for forgotten remains.

They know it sounds kind of weird.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): When I was telling people, this is what I'm doing this week. I'm going to visit some folks who rescue human remains. Um, they were like, what the --? So like, what do you say to, what do you, how do you explain to people like...

Justin Capps: Get to know someone like us first because this is honestly not just unique, but it's trailblazing. It's different. It's something nobody's ever really seen before. And we have the opportunity to do something wild, crazy and cool. And you're standing here in my living room seeing this yourself. There's nothing gross here. There's no blood, no guts and no gore. This isn't set up like Halloween or something. ...

Ally Jarmanning: And it really isn't. It's tasteful. The skeletons are in glass display boxes, or hanging in coffins. They all have names. It's almost museum-like.

I'm not grossed out by it at all. I'm more intrigued. I'm interested in their interest in it all. I do wonder though, how different are Justin and Sonya than any other collectors?

They may use different words to describe what they do and not buy their skeletons off a website or Facebook, but they still own human remains. I keep wondering how Amber or the other Harvard victim families might feel about this.

It's complicated.

That said, it's been a nice evening among the skeletons. Justin grilled us some steaks, and Sonya made mashed potatoes and asparagus. Sonya's cleaning up the dishes while Justin gives me a more thorough tour of the living room.

He's showing me Edgar — a very tall skeleton they aren't quite sure the sex of, when I look down by Edgar's feet and see a teeny skeleton on a wooden base.

Justin Capps: That's Mini Me.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Is that plastic, I assume?

Justin Capps: (laughs)

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): No? What is that? What is that?

Justin Capps: That's Mini Me.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): OK, you gotta explain this.

Justin Capps: Mini Me is a 36-week-old fetal skeleton.

Ally Jarmanning: A fetal skeleton. It can't be more than a foot tall, the bones so tiny they look like toothpicks. I can see the four pieces of its skull not yet fused together, what would be the baby's soft spot. It's so delicate. I'm a little stunned, and I don't know what to say.

I think about my own baby. He’s about to turn 1. And how when he was first born, I’d hold him and tuck his little head underneath my chin as he slept. His tiny, not fully formed skull, not much bigger than this skeleton’s, protected by me, his mother.

Justin gingerly pulls the fragile skeleton out of the cabinet.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Wow.

Justin Capps: You see Mini Me's held together with little nuts and bolts and springs and coated in resin.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): How old do you think this is?

Justin Capps: Uh, just a couple years.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Where did you get that?

Justin Capps: Online.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Now was that a purchase or was that a...

Justin Capps: Yeah, um, I bought that. There's just some things people will not give you for free, so.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): How much does it cost to purchase a fetal skeleton?

Justin Capps: Like that?

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Yeah.

Justin Capps: Uh, about seven grand.

Ally Jarmanning: $7,000. Justin says he didn't pay that amount. Only $200. But I'm wondering what happened to the whole "we don't buy human remains" moral code?

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): And you feel like that's that's OK. Like you can square that with your...

Justin Capps: Uh, with with my maker?

Yeah, because there's a rescue. There are situations that the skeletons are in that if I have the opportunity to get them, I will.

But in order for me to get them out of there, it's going to cost money.

Ally Jarmanning: I look closer at Justin's fetal skeleton. I keep thinking of the baby in Arkansas, Lux, who was stolen and sold to Jeremy Pauley. I don't think Justin stole this, or knowingly bought something that was, but I can't help but wonder who this 36-week old baby was. Who were the mother and father?

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Where do you think it came from?

Justin Capps: I don't know, but whoever articulated it did a really good job, as you can see.

And you see how small the springs are on the jaw and all that? I mean, uh, someone with some serious skills did that.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): But it makes me, it just makes me wonder, like, was this a fetus that was supposed to go back to someone? Or was it just going to be...

Justin Capps: I don't think so, because that came with a receipt.

Ally Jarmanning: I've been asking about the fetal skeleton for a few minutes now and I can sense a little tension. I let it be. Before I leave Justin and Sonya, I ask the bigger picture question that's been on my mind.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Do you think, um, I mean, do you wonder, whoever these people were hundreds of years ago, how they would feel about being in someone's living room?

Justin Capps: You know, I wonder about that. I wonder how many of them even had a choice to become medical specimens. And the only way I was able to get over any of it was to have a sit down conversation with each one of them that come in here and explain to every one of them, like, I'm not going to disrespect you. I'm going to treat you like you should be treated. As you can see, I do that. I'm not going to let anybody abuse you. I'm going to treat you like my family. You know, you're going to be living in my home. I might as well get used to you being here. We might as well get used to each other. So, don't haunt me.

Ally Jarmanning: I ask a version of this question to almost every collector I speak to, and I speak to a lot.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Do you wonder at all about like, who these people were before?

Collector 1: I do. I definitely wonder who they are, who they were. Like I believe there's more than this, right, like this flesh and blood, um, so I look at it as a scaffolding of a life that has moved on.

Collector 2: Unfortunately, I'll never know that person's name who's in my cabinet. But they're kin to me.

Collector 3: Yeah, I mean, it's, it took a whole life to live, for this skull to be there. So there's definitely some, some heaviness to it, you know. Which renders it more than just an object. They're not, they're not objects to just be played with and they're there to be respected.

Mike Drake: If somebody came to me and said, I know 100% that is my great grandmother, and I would like her back, I would give it to her.

Uh, but besides that, I don't ever really think about who that was, any more than I think about what happened to the turtle that was in that shell.

Ally Jarmanning: I visited Mike Drake at his Queens, New York apartment. It is a collector's dream in there — every wall and shelf is filled with knick knacks and oddities — glass eyes, masks, molds of teeth, turtle shells. There's a reason Time Out New York called him a curator of curiosities.

Mike was a collector from a young age, growing up in New Jersey. His gateway drug was a little gargoyle figurine his mom got him after he watched the "Hunchback of Notre Dame."

Mike Drake: And, it went from there.

Ally Jarmanning: By 16, he was fixated on owning a human skull. He was influenced, he thinks, by art. Portraits of learned men always had a skull on a shelf or in the subject's hands. You know, Hamlet: "Alas, poor Yorick, I knew him."

Mike Drake: From an artistic point of view, that was really in vogue for a certain period. If you were like a wealthy merchant or you wanted to show that you were an educated person, when they painted your portrait, you would have a skull in there somewhere, like, "Hey look, I have a skull."

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): It was a mark of some kind of class.

Mike Drake: Yeah. Ha.

Ally Jarmanning: He still has that first purchase he made at an oddities shop in New York City.

Mike Drake: So my first skull is right there on the top shelf. And I remember I saved up and I was so excited I went and I bought that. That's the only one I've kept. I've had others over the years, but that's my first and my favorite.

Ally Jarmanning: It cost him a hundred bucks. It was and is basically legal for Mike to buy a skull or any other human remains. There’s no federal law against body parts buying. State laws are patchy and mostly unenforced. It's not legal to steal and sell human remains of course, but other than that, it's just like any other object for sale in a store.

In the '90s, Mike actually worked in the skeleton trade.

The internet was just becoming a thing, and there were lots of people who needed skeletons. And there weren't a lot of places to buy them.

Mike Drake: This is going to be so hard for people now to conceive of, but if you wanted a life size skeleton for whatever purpose, for medical purpose, for a film, for a play, just for decoration, you either bought a real human skeleton from a medical supply company, or you bought a very expensive, which cost more than a human skeleton, a plastic reproduction.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Did you ever think about when you were, you know, being the middleman of the skeleton trade, where they were coming from, like who the people were?

Mike Drake: Not really, no.

I knew that, uh, a lot of them were coming from India and then from China, but as for who the actual people were, I did not really think about it, no.

Ally Jarmanning (on tape): Some people might be surprised by that.

Mike Drake: I don't want to sound uncaring or ghoulish, but I separate the person from the meat. And I don't think of myself as the meat. I'm really my brain, and my thoughts, and my spirit and maybe my soul. Once my body is turned off forever, this isn't me. This is just my container, my wrapper.

Ally Jarmanning: Mike’s pretty unsentimental about this. Which, I guess makes sense if you used to move skeletons around in your Chevy Cavalier.

But he got me thinking. About what a dead body is. Is it a person still? Or just an object. A container, no longer in use, as Mike put it. A wrapper that can be thrown away.

Our bodies, are they something to be saved and treasured? Or tossed?

At medical schools, most anatomy professors and students have an answer: the donated bodies should be treated with dignity. Cared for like they were actual patients. Kept together and buried or returned to their families.

But it hasn’t always been this way.

Next time, on Postmortem, we go back to school – medical school.