Advertisement

More Than A Game: What’s Behind The High Cost Of Being A Sports Fan

Resume

Outside Gillette Stadium, about an hour before a late-December game, it’s time for some homemade apple pie moonshine. Shot glasses are spread on a folding table and filled. Then, there’s a toast.

“Every year we head to the playoffs and it looks a little different,” says Jim Politano of Foxborough. “To four more wins.”

The tailgate gathering is a mix of season ticket holders from nearby towns and friends from as far away as Connecticut. They make the pilgrimage to Gillette for a fan experience that goes beyond the field.

Over the last few decades, sports have become big business and big entertainment. Super Bowl Week, the corporate-party-fueled buildup to Sunday’s showdown between the San Francisco 49ers and the Kansas City Chiefs, is the ultimate example. The cheapest ticket currently available to Super Bowl LIV is more than $4,000. That comes as no surprise to fans. The high cost of being a fan — the time and money cost — is now part of the experience. It’s a non-negotiable.

To understand why it costs so much to be a fan, we asked top executives from the Patriots, Red Sox, Celtics and Bruins for their perspective. They pointed to several factors, including the social element, the challenges of supply and demand in a sports-obsessed city, and the desire to provide more personalized—and ostensibly better—service to fans.

Bottom line: Teams are selling more than the game.

Fans wouldn’t buy tickets “if there wasn't something completely unique and irreplaceable about the experience,” says Patriots chief marketing officer Jen Ferron. “Something we pride ourselves on is having that communal aspect on game day.”

We also asked fans whether they think it’s worth it. The communal aspect factored heavily into what made the fan experience valuable.

On a game day with a 1 p.m. kickoff at Gillette, Patriots fan Wade Alix leaves his home in Easton, Connecticut at 5 a.m. He often doesn’t return until 11 p.m.

That’s why he’s been to only four or five games over the last 20 years. But when he does go, he says it feels like a special event.

“I just can’t take an entire day out of my weekend, every weekend, with it. But when you do get a chance it’s well worth it,” he says.

Like a lot of fans, Alix heads to Gillette early for tailgating. But before the partying begins, fans battle traffic down Route 1. The good news: The farther away you park from Gillette, the cheaper the cost. About a mile away, it’s $40. About a half mile away, it’s $60.

Advertisement

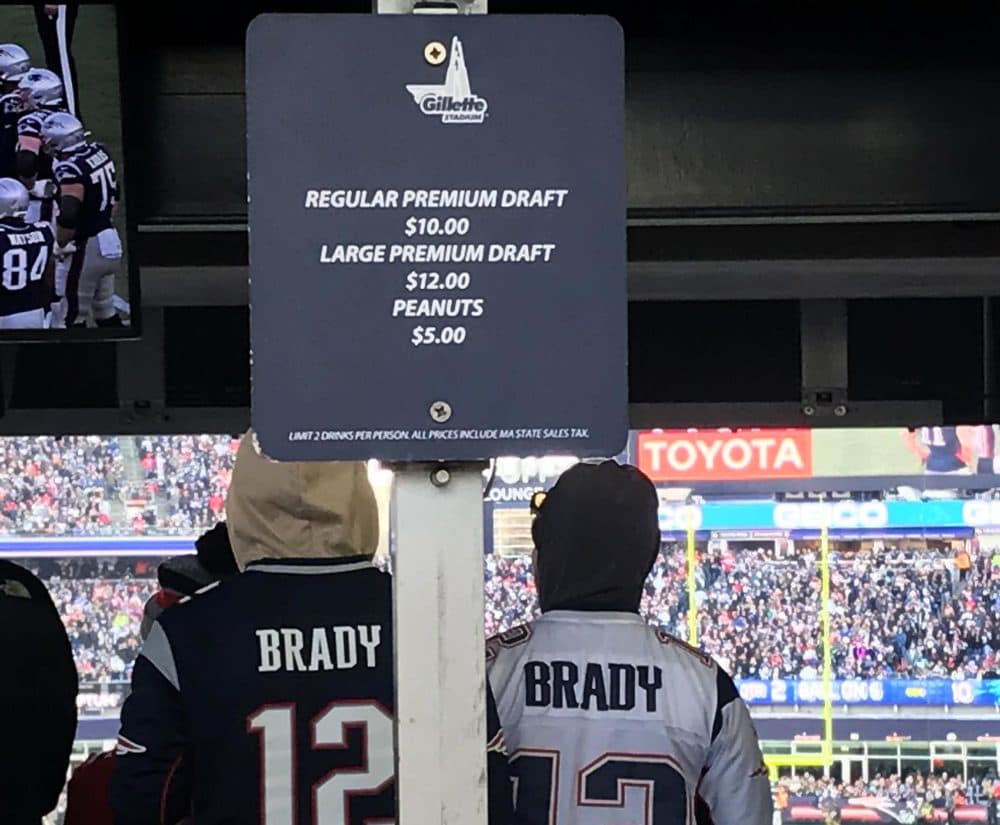

Inside the stadium, you pay $5 for hot chocolate, $10 for a regular-sized premium draft beer, $11 for a steak sandwich. Imagine those prices multiplied for a family of four. (Well, not the beer).

Then, of course, there’s the big one: the ticket price. Patriots fans without season tickets paid more than $700 on average on the secondary market in 2019. That’s where supply and demand directly dictate prices and where many people purchase tickets.For the 2019 season, the average price for tickets sold directly by the team was $129.

The costs---the time and money--add up quickly. The same is true at Fenway Park and TD Garden. Teams know fans sacrifice a lot. But these days, team executives think beyond the game.

“You have to have a competitive team and a team built to play baseball in October,” says Red Sox CEO Sam Kennedy. “But you have to give them a lot more than that because it is not just winning and losing. Baseball is the ultimate social experience. Fenway Park is the most social experience.”

Talking in a conference room high above third base, Kennedy glances at an empty Fenway, then continues, “There's an old adage, if you want to take someone on a first date, whatever age you are, Fenway Park is the best place because you have an hour or two before the game. You have a three, three-and-a-half hour game. You have postgame. There's bars. There's restaurants. It is very, very social. So we really try and lean into that.”

Giving fans the “ultimate social experience” is one way to justify the price tag that comes along with sports fandom. It’s also one of the reasons the cost of being a fan has grown at such a rapid rate.

The teams say they’re reinvesting the money into the fan experience. That includes technology, new arena amenities and, of course, the product on the field or the court or the ice.

In Boston, not only do fans want to be entertained, they expect to win championships. And we’re not breaking any news here: winning can be expensive.

“What we can always show our fans is we put the money into player payroll,” says Celtics president Rich Gotham. “And the great thing about my job is I'm not trying to generate a strong top line, to show double-digit quarterly growth to Wall Street analysts. I'm doing it so we can pay players and win championships.”

The way Bruins president Cam Neely sees it, when it comes to the fan experience, team performance “drives the bus.” He says the Bruins try to “make sure that we're pricing it based on where we think the team is going to be. It's a delicate balance … You try to get it as close to right as you as you can. And that's doing the right thing by ownership and doing the right thing by our fan base.”

Local team leaders say they think long and hard about how to do right by fans.

“I think the old way of pricing your inventory was, if you signed a big free agent, raise ticket prices,” says Kennedy. “If you win the World Series, hit ‘em hard, have a double-digit ticket price increase.”

Kennedy mentions how recent ticket price increases for the Sox have ranged from 1-3%, right around the annual cost of living adjustment. The goal is to make the increases regular and predictable. The way Kennedy sees it, “that’s good for the customer.”

Using a combination of data and experience to gauge the market, Kennedy says the Red Sox learned to be “far more strategic on the low end, on the high end.”

“That’s led us to this environment — we have over 150 price points depending upon date of game, opponent, anticipated weather,” he says. “I mean, if we could figure out the weather in advance, we'd be in great shape.”

In addition to the variable pricing Kennedy talks about, there’s also dynamic pricing. That’s what happens with airline tickets and, in sports, with single-game tickets and with secondary market tickets. With dynamic pricing, ticket costs can fluctuate right up until game time.

“In some cases, there might be someone buying a ticket for less than we sold it to a season ticket holder,” says Gotham. “But if that's what you need to do to fill the seat, you know that plane's going up in the air. We want the seats full.”

Nowadays, filling seats is about more than anticipating the demand for tickets. There’s the demand for different food at concession stands, for more mobile content and for better access to arenas. With tens of thousands of fans going to Boston arenas every game, every season, there’s no shortage of demands to track and try to satisfy.

“We're a very data-driven organization,” says Ferron. “We like to get fan feedback. It's really making sure that we understand what our fans want and that we are reactive and responsive where appropriate and when applicable.”

Ferron knows that Pats fans always want parking closer to the stadium. Last season, the team introduced free stadium parking. But fans who take advantage of the deal have to wait 75 minutes before they head home. That helps alleviate some of the post-game congestion on Route 1.

On the other end of the spectrum, there’s the Putnam Club, the stadium’s exclusive, premium seating section. That comes with parking near the special club entrances and passes that allow some fans to bypass traffic on Route 1 and take back roads to the stadium.

In 1999, Putnam Club seats near the 50-yard line cost $6,000 per seat per season, and the team required a 10-year commitment. According to Patriots spokesman Stacey James, while the price for club seats has increased over the last two decades, members lock in rates based on when they sign on and for how long they extend. James also noted that many of the founding members are still active seat holders.

Travel and parking perks are part of what team executives call the “driveway-to-driveway” game experience, stretching from the moment you leave your home until the moment you return. If you pay for it, the driveway-to-driveway experience takes less time and offers more luxuries. Think first class versus economy class.

Now, imagine airlines not knowing the names of passengers in their planes. That was true of sports teams for years until mobile ticketing. The latest advance? Teams can track the chain of custody of a ticket. The Kraft Analytics Group and the Patriots are industry leaders when it comes to collecting fan data.

If your favorite aunt gifts you one of her season tickets for a Patriots game, the team will know it’s you sitting in the seat instead of her.

“That allows us to have a lot of one-on-one communication with people,” says Ferron. “We can get to them in advance. We can send push notifications. We can send emails. Knowing who has that ticket and who's coming into the building, I think has opened up so many doors for us that allows us to just be more responsive, more intelligent, more nimble in reacting and responding to what we want to do.”

Take those push notifications. They might tell fans when a parking lot is full or when it’s best to get to the stadium gates or, once inside, where to get those $9 chili cheese fries they’ve been craving. It’s all about building a strong relationship between the team and its fans, making fans feel personally connected to the Patriots.

After the game, teams want fans to remember more than the final score or what they paid to get into the arena or how much those fries and steak sandwiches and hot chocolates cost.

“So much of what fans are doing today is documenting their experience,” says Ferron. “And so, if they have a memorable moment and they have a photograph of that, they share that with a friend or a family member or a community. [We want] that sense of belonging. We want fans to come to our stadium and see our games and feel as if they're a part of the team.”

Back at the Patriots pre-game tailgate with apple pie moonshine on hand, you won’t find any disagreement. If you ask Alix what makes it all worth it, he says, “The games, the fans, the excitement in it, just the whole feeling of community, Patriots community.”

That’s what teams want to hear.

But if the teams’ analytics and experience tell them anything, sports fans can be tough customers. The competition to win—and keep—fans never ends.

Shira Springer is WBUR's sports and society reporter.

Ben Shields is a Senior Lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management and author of several books including “The Elusive Fan: Reinventing Sports in a Crowded Marketplace.”

This segment aired on January 31, 2020.