Advertisement

At the Brattle, the sordid and sublime films of Jean Eustache

It feels like for as long as I’ve been reading about movies, I’ve been reading about “The Mother and the Whore.” Winner of the Grand Prix at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, writer-director Jean Eustache’s towering, 219-minute chronicle of a messy ménage à trois was named the best movie of the 1970s by the venerable French film journal Cahiers du Cinéma, yet it has long been difficult to see on these shores. As far as home video goes, the picture never made it past VHS and seldom shows at repertory houses. A fiercely private filmmaker who took his own life in 1981 at the age of 42, Eustache’s brief, prolific career has made him a mysterious, almost mythical figure among international cinema aficionados, his work more written about than seen.

That’s about to change, thanks to “The Dirty Stories of Jean Eustache,” a traveling retrospective from Janus Films showcasing a dozen of the director’s documentaries, shorts and dramatic features. After playing to blockbuster business this summer at Lincoln Center, the series arrives at the Brattle Theatre this weekend, headlined by a stunning new 4K restoration of “The Mother and the Whore.” Films with such outsized reputations don’t always live up to them, but an afternoon spent finally catching up with Eustache’s masterpiece while visiting New York this past July turned out to be one of the great moviegoing experiences of my life.

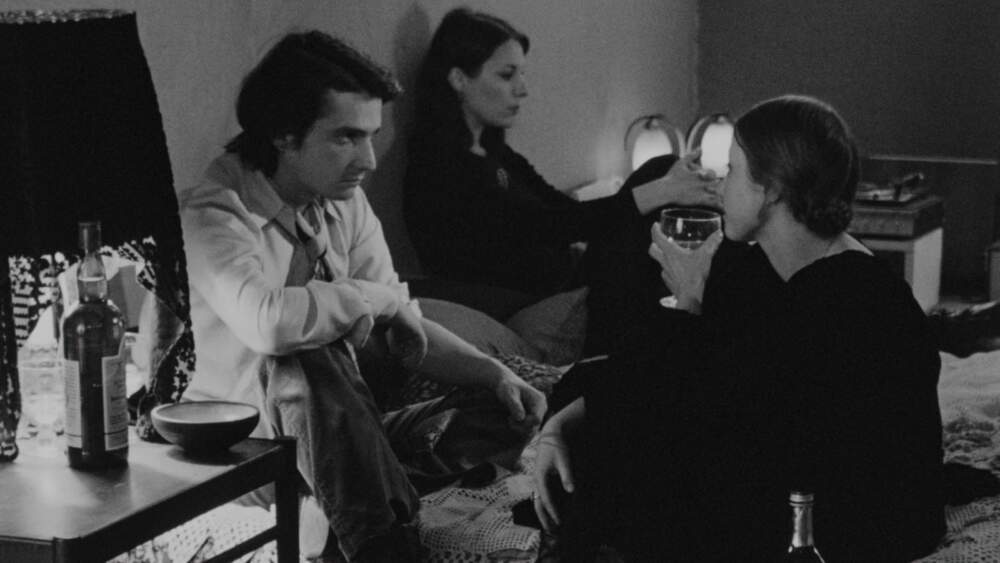

A fitting epitaph for the French New Wave, it’s one of those films that feels like it defines a generational turning point — when the idealism of the 1960s soured into the selfish libertinism of the ‘70s. It’s about children of the revolution adrift without a cause and emotionally ill-equipped for new freedoms they have no idea what to do with. Jean-Pierre Léaud stars as Alexandre, an indolent, pseudo-intellectual blowhard living off his older lover Marie (Bernadette Lafont) while sleeping around with a proudly promiscuous nurse (Françoise Lebrun) closer to his own age. The title is a half-kidding provocation, symptomatic of our protagonist’s coarse worldview and his limited understanding of the women in his orbit. As we discover during the movie, Alexandre’s a pretty limited guy.

“The Mother and the Whore” is nearly four hours of fighting, fornicating and philosophizing in cafes and cramped apartments — maybe the French-iest movie ever made. It’s pitilessly funny and unutterably sad. Via an atmosphere of everyday intimacy and endlessly elongated arguments, the film becomes an enveloping experience. It seems to wrap itself around you until you feel like you’ve been living inside of it for a little while. Eustache conjures the sidewinding, stutter-step pacing of real life, complete with occasional, intentionally tedious idylls before the emotional fireworks resume. With the best films, it can take a little while to fully come back to your own reality when they’re over. “The Mother and the Whore” took me all day.

Eustache got his start in documentaries and also worked for Cahiers as a film critic. You can see the two career paths entwined in his magnum opus. A work of autofiction, most of “The Mother and the Whore” was shot in the apartment and dress shop of costume designer Catherine Garnier, a former lover of the filmmaker and inspiration for the character of Marie. Lebrun was not a professional actress but another of Eustache’s ex-girlfriends. The extent to which we’re watching a true story can only be surmised by the director’s cagey admission that “the films I made are as autobiographical as fiction can be." It is not, to say the least, a flattering self-portrait. “The Mother and the Whore” feels more like a confession, an artist laying his worst qualities bare before the world in search of absolution. (Chillingly, Garnier died by suicide days after seeing the finished movie, leaving Eustache a note: “The film is sublime, leave it as it is.”)

Alexandre is a pompous man-child enchanted by the sound of his own voice. He pontificates about the curative properties of physical labor while Marie does the dishes. Impishly charming in spite of Alexandre’s awfulness, Léaud already had a lifetime of goodwill built up with audiences who'd watched him grow up onscreen as Francois Truffaut’s alter-ego in “The 400 Blows” and the Antoine Doniel films that followed and also as the lovesick young wannabe revolutionaries of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Masculin Féminin” and “La Chinoise.” There’s something almost vandalous about Eustache stealing his predecessors’ favorite onscreen surrogate, only to cast him as a poseur and a cad.

Similarly, Lafont was once known as “the face of the Nouvelle Vague,” most memorably playing an unattainable object of beauty chased by a throng of pubescent boys in Truffaut’s 1957 “Les Mistons.” Yet as Marie, she’s no longer desired by these callow youths, cast aside as an old maid at the age of 35. The abuse of these beloved icons is part of what gives “The Mother and the Whore” such a gnarly, subversive kick, like it’s bringing a cherished era of cinema to a bitter, unromantic end.

Perusing the other films in the Brattle series, one sees similar acts of blasphemy and bouts of bad taste, often undeniably hilarious in spite of the viewer’s better judgment. 1974’s “My Little Loves,” the director’s reminiscence of his rural childhood, begins with the voice-over narration of our protagonist complaining of an erection in church while conspiring to bump into the young girl ahead of him in the communion line. The uproarious 1966 “Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes” finds Léaud playing a dirtbag department store St. Nick, groping female shoppers four decades before Billy Bob Thornton in “Bad Santa.” But the most revelatory discovery, at least regarding Eustache’s methodology, might be the 1977 short from which the retrospective takes its title.

Advertisement

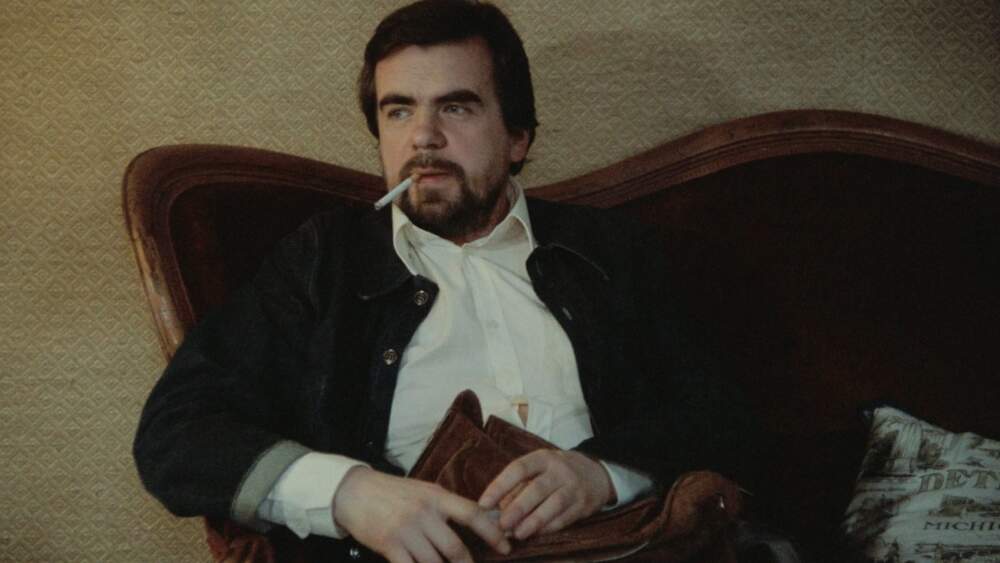

“A Dirty Story” starts with legendary French thespian Michael Lonsdale entertaining a small, sophisticated audience with an appalling, yet strangely captivating monologue about a café where men used to line up at a peephole to spy on women while they were using the toilet. Halfway through, Eustache turns his camera toward another, grubbier man — clearly not a movie star, presumably the tale’s real-life protagonist — telling the same story without any of Lonsdale’s comic timing or innate elegance, to the revulsion and disgust of his listeners. The structural switcheroo is another confession, I think, from a filmmaker who habitually honed his ugly life experiences into art, showing us how it’s sometimes only a matter of presentation separating the sordid from the sublime.

“The Dirty Stories of Jean Eustache” runs at the Brattle Theatre from Friday, Sept. 8 through Wednesday, Sept. 13.