Advertisement

The Third Act

Julieanna Richardson's 'third act': The Harvard-trained lawyer left corporate life to document the Black experience

Resume

This story is part of WBUR's "The Third Act" series, highlighting people who worked full careers and reinvented themselves later in life, often in surprising and inspirational ways.

On a summer afternoon in Chicago, Julieanna Richardson sorted through a heavy bundle of keys to unlock a door in an office building not far from downtown. She entered a room full of metal shelves, packed with thousands of folders containing the stories of Black Americans.

"These are the paper records," she said, looking across the room. "We have their correspondence, biographical information, transcripts — and we're running out of space."

Whose history matters, and who gets to write that history? Those questions inspired The HistoryMakers, an ambitious project launched by Richardson 20 years ago. The nonprofit has collected reams of documents and recorded thousands of video interviews with Black Americans, ranging from politicians and business moguls to artists, actors and musicians.

For Richardson, documenting these stories is an important part of guarding history and showcasing the value of the individuals and their lived experiences.

"You preserve what has value," she said. "You don't destroy it."

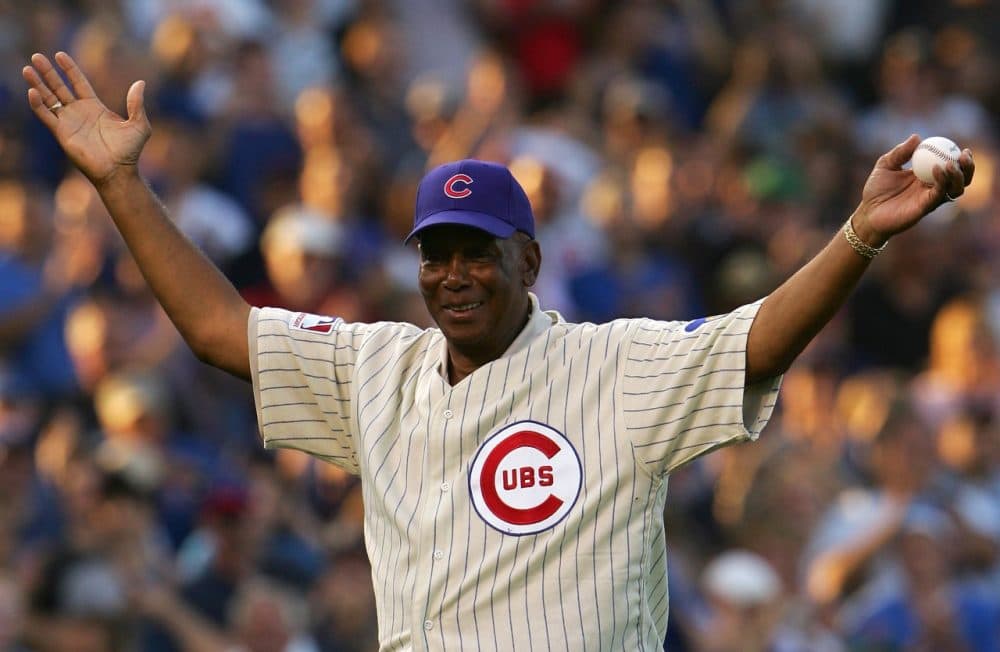

The HistoryMakers’ archive includes interviews with athletes like Ernie Banks, who played in the Negro Leagues, became an All-Star shortstop and first baseman with the Chicago Cubs, and ultimately was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Banks described playing ball as a kid, with “no bats, no balls, no gloves, no nothing." They used old rag balls, he said. And for a bat "we used a broomstick."

The collection features poet Maya Angelou, recalling a meeting with writer Langston Hughes.

"He invited me to his house in Harlem," Angelou said. "I don't remember anything he said, but I remember he was very kind."

And there’s an interview with a young Illinois state senator.

"I wasn't really focused on running for office per se," said a strikingly young-looking Barack Obama in a 2001 interview. "I was more interested in helping to build an agenda for the African American community politically."

Seven years later, he was elected president of the United States.

But before Richardson began archiving all these vibrant stories, she had to write her own. She began her career as a Harvard-trained corporate lawyer and took a number of detours before birthing the HistoryMakers in 2003. At 69, she is one of a growing number of Americans who have reinvented themselves in mid-life or later, in unusual and inspiring ways.

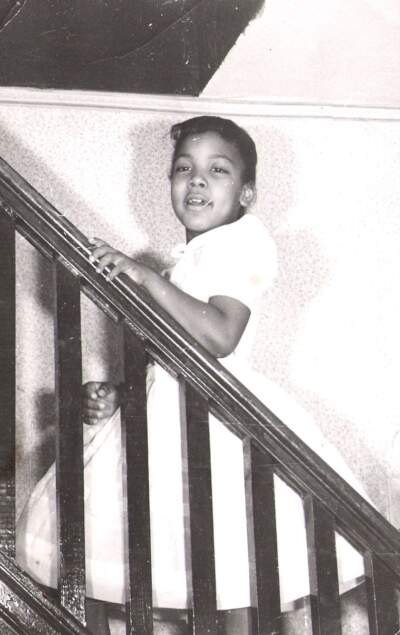

The early part of Richardson’s life played a big role in what followed. She grew up in Newark, Ohio — a tiny city east of Columbus — where she was the only Black girl in her class at school, she said. She quickly began to understand that something was missing.

"There was no history, not Black history," she said. "There was not even a sense of where my place was in American society."

She learned about George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and the War of 1812. She also knew about slavery, and that her great grandfather, whom she called Papa, had been enslaved.

"It was my job to go and get him ice water," she said. "And slaves never wanted to talk about slavery, but we would whisper, 'Papa was a slave.' So that's all we knew."

As a child, Richardson wasn't even taught about the Black history in her own city, like the story of Edward James Roye, who was born there in 1815, and went on to become the fifth President of Liberia. She said Roye's story was part of "a rich Black history that I knew absolutely nothing about."

It was at Brandeis University, as a sophomore in 1974, that Richardson had a life-changing epiphany, she said. Studying theater arts and American studies, she traveled to New York to study the Harlem Renaissance at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. While conducting her research, she discovered that the iconic American song, "I'm just wild about Harry" — long associated with President Harry Truman — was written by a pair of Black songwriters, Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. She was thrilled.

Advertisement

"To find out that it had been written by this Black songwriting team was just over the top," Richardson recalled.

The revelation inspired Richardson to record a series of interviews with other prominent Black Americans. In hearing their stories, she uncovered hers.

"I had a history to call my own," Richardson said in a Ted Talk in 2022. "I too, according to Langston Hughes, 'I too am America.' And from that day forward, my life was forever changed."

But there would still be a series of unlikely twists and turns before she arrived at the HistoryMakers. Richardson had wanted to work in theater, but her father urged her to become a lawyer, so she headed to Harvard Law School, hoping to become an entertainment lawyer and stay connected to the arts. After graduating, she landed a job at a Chicago firm, where she was the sole Black attorney and only the second woman to work in the corporate department.

Richardson said she was "very upfront" when she started the job and asked a senior partner what happened to the other woman who had worked there. She said the partner told her, "Some of the clients didn't want to deal with her."

"And I said, 'Well, what about me?' " she recounted. "The partner said, 'Some of them won't want to deal with you because there aren't [many] Blacks in corporate America.'"

After two years she resigned.

She went on to become the cable TV administrator for the city of Chicago and started her own production company. Then, in 1985, she tried something else. She raised a million dollars and set up one of the first regional home shopping channels in the country. But it didn't last.

"It went belly up," she said.

Richardson moved on to work for Comcast and C-SPAN, until the cable industry restructured and she was out of a job again. She couldn't go back to corporate law, she said, because “too many years had passed.”

Feeling lost and confused, she had no idea what to do next.

"But I say often that sometimes at your darkest moment, the thing that's intended for you is right there," she said.

An echo of the epiphany she’d had at Brandeis sparked her next idea: a plan to record and archive Black oral histories. There was a big obstacle, however: Richardson had no financial backing for the project.

Her friends thought it was a terrible idea and tried to talk her out of it. Even her mother, Margaret Richardson, had doubts.

"At first I thought, 'Oh God, but no,'" Margaret Richardson said with a laugh, adding that her daughter embarked on the HistoryMakers with "nothing."

"Getting people to understand — including me — what the dream really was, is hard work," she said.

But Richardson forged ahead. She began her new venture with a laptop on her dining room table. Twenty-three years later, she has raised more than $36 million and recorded close to 3,600 interviews, which are accessible through colleges and universities across the country and through the Library of Congress, a major coup for the project.

Despite her initial misgivings, Richardson’s mother is proud of what her daughter has accomplished. In fact, at age 93, Margaret Richardson helps run the HistoryMakers’ office in Chicago. She said her late husband, who had pushed their daughter to become a lawyer, also believed in the importance of “giving back,” and would be equally proud.

“His spirit is happy now,” Margaret Richardson said.

After chapters as a corporate lawyer and working in television, HistoryMakers became Julieanna Richardson's “third act.”

"You get to a point where you start asking, 'What is going to be your leave-behind?'" she said. "If we do this right, it will be something that hopefully makes society a richer place."

Every day, some 10,000 baby boomers reach retirement age, but many aren't ready to stop working, either because they can't afford to, or, like Julieanna Richardson, they have more they want to accomplish.

"There are more transitions during midlife than any other time in life," according to Barbara Waxman, a gerontologist who studies this period of living. "And yet we have this idea that it's stagnant."

Waxman said when people like Richardson find themselves searching for new purpose, the struggle is often referred to as a midlife crisis. But according to Waxman, it's not a crisis, it's an opportunity.

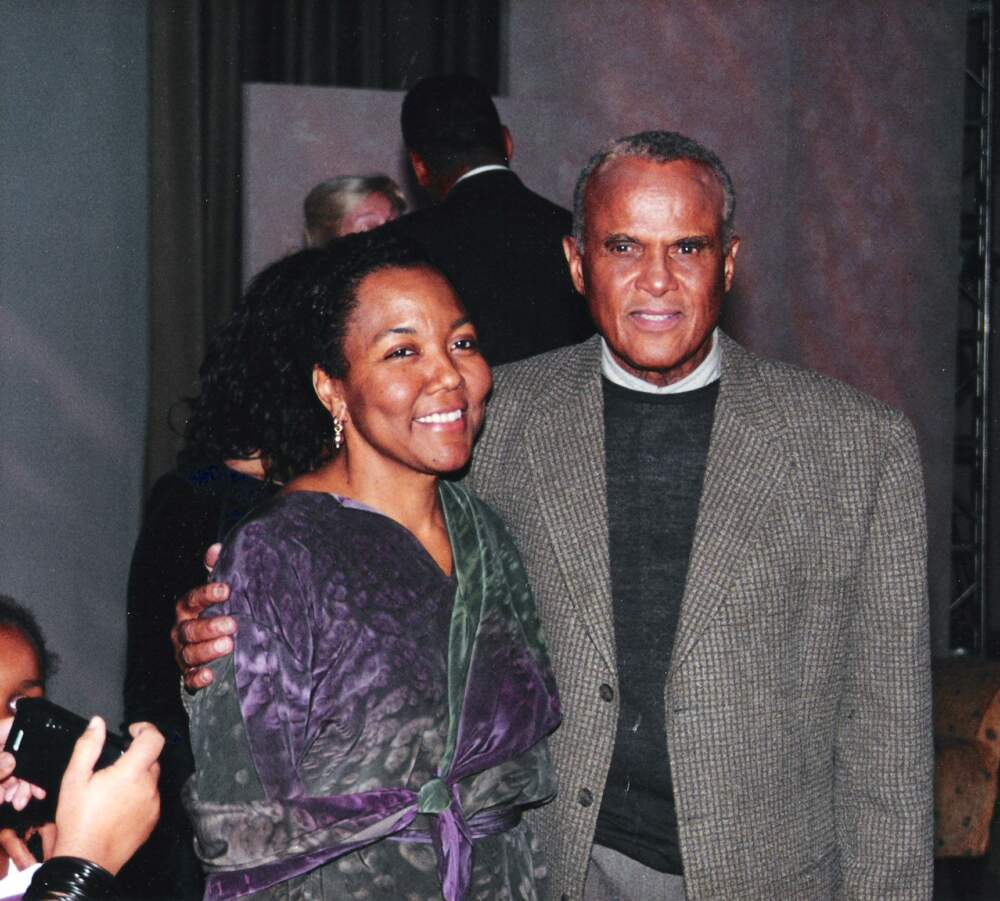

Back in Chicago, the walls of Richardson’s office are lined with photos of people who are now part of the HistoryMakers video archives — from famed singer Dionne Warwick to the late singer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte and musician Ramsey Lewis. But she said there is a lot more work to do; she feels an urgency to gather more interviews before any stories fade away.

Richardson mourns the fact that lots of written materials documenting Black history from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries have been lost forever.

"I'm so concerned about our nation losing the 20th century," she said. "So I worry about that."

If HistoryMakers began as a discovery, then a dream deferred, Richardson said it has been a journey worth taking.

"What are dreams if they’re not to be explored?" Richardson said. "There was no bridge to take me. We built the bridge as we crossed."

This segment aired on October 30, 2023.