Advertisement

Horseshoe crabs spawn with wild abandon as state rolls out new protections

Resume

Horseshoe crabs are not endangered or threatened in Massachusetts, but their numbers are at historic lows. To protect the species, state wildlife officials are rolling out new regulations. As of 2024, horseshoe crabs can no longer be harvested in Massachusetts during spring spawning season, from April to June.

The state's horseshoe crab population has declined for several reasons, according to Mark Faherty, science coordinator for Mass Audubon's Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary. For decades they were considered pests; kids on Cape Cod could get a couple of pennies for each crab they killed — tossing it in the dunes to die and snapping off its tail as proof for town officials. "They were worth more dead than alive," Faherty said.

Today, horseshoe crabs are harvested for bait in the whelk fishing industry, and for use by biomedical companies. A protein in their pale blue blood is used in a test for bacterial toxins in medical products.

But they are also valuable players in coastal ecosystems. Horseshoe crab eggs, especially, are a vital food source for migrating shorebirds like the near-threatened red knot.

WBUR visited Orleans, on the Cape, with a team from Mass Audubon to witness a horseshoe crab spawning survey, and learn more about these ancient creatures.

Here are some of our favorite photos, and facts about these prehistoric animals:

Horseshoe crabs have been around much longer than humans — more than 400 million years. They have survived mass extinctions, ice ages and the splintering of Pangea into separate continents. Through it all, they've remained largely unchanged.

The crabs have a distinctive look, with shells resembling brown, ridged helmets. Their long spike of a tail, known as the telson, helps them flip over if they get stuck on their backs. Their five pairs of eyes give them excellent night vision.

While some may find their appearance unsettling, horseshoe crabs are harmless to humans.

They have no teeth, so they crush their food between their legs before consuming it. They eat worms, clams, algae and other tidbits they can scavenge.

May is peak spawning season for horseshoe crabs. A female horseshoe crab will burrow into the sand near the high tide line and lay hundreds of pale green eggs. Often, she'll drag along a smaller male, which clings to her back with special claws, ready to fertilize the eggs when the opportunity arises.

A female can lay around 80,000 eggs in a season.

On some beaches, like the one we visited in Orleans, males outnumber the females. During spawning season, males will crowd around a single female in a "mating cluster," clamoring to fertilize her eggs.

In places with better protections for horseshoe crabs, like Cape May, New Jersey, some beaches are mobbed with thousands of crabs during spawning season, with dense clouds of migratory birds passing through. The crabs and birds create such a spectacle that it's become a tourist attraction.

The numbers are more modest in Massachusetts but should improve with the new protections. Teams from Mass Audubon have been counting spawning crabs at this beach on the backside of Nauset Spit for more than a decade.

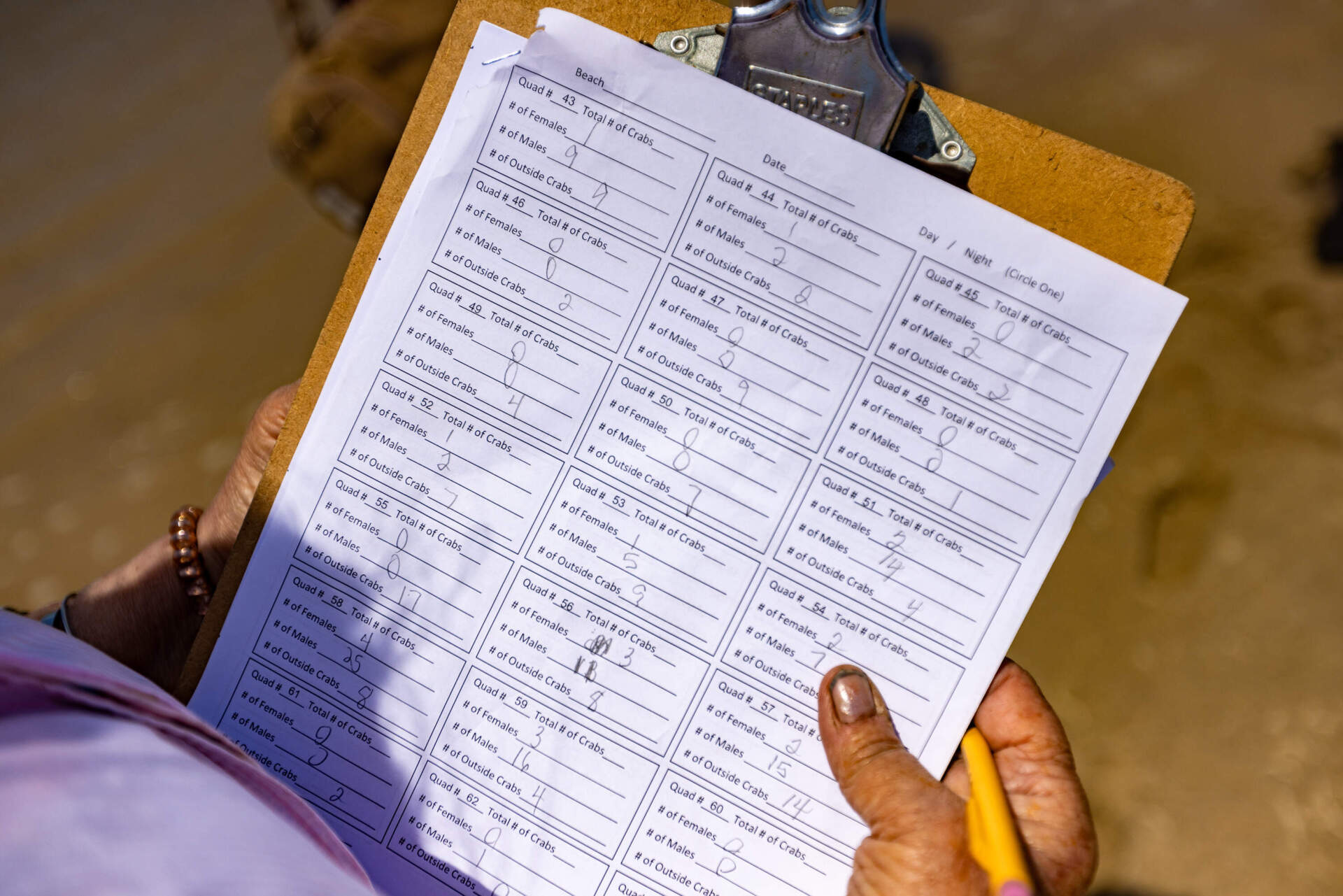

Volunteers use rope to measure out a 16-by-16-foot square on the beach, count the crabs inside, then step down the beach for the next one. It's kind of like watching the chain crew at a football game as they follow the ball down the field.

On this day in Orleans, the Mass Audubon volunteers counted 279 crabs: 55 females and 224 males, about average for this time of year.

Mass Audubon staffers also tag horseshoe crabs to study their range and habits. If you find a tagged horseshoe crab, you can punch the tag number into the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s website, and they'll let you know where the crab was originally tagged. (You can get a certificate for participating!)

Horseshoe crabs may have outlasted the dinosaurs, but they still face challenges. In Massachusetts, people can harvest them after spawning season. And climate change is prompting stronger storm surges and sea level rise, which erode the beaches where they lay eggs.

Still, the scientists and volunteers are optimistic about the horseshoe crabs' future.

"I just like the fact that they're prehistoric, that they've been here for so long. I mean, it's really amazing. They’re our ancestors," said Audrey Stage, who has been volunteering on the crab count for about six years. "They never give up."

This segment aired on May 31, 2024.