Advertisement

Business groups battle over the spirit of downtown New Bedford

Love him or hate him, everyone in downtown New Bedford seems to be talking about Marco Li Mandri. The consultant from San Diego arrived here about 10 years ago, at the invitation of a small business association looking for new funding sources to make downtown a more attractive place to shop and dine out.

Li Mandri recalled in a recent interview that he immediately fell in love with New Bedford, and its pretty streets sloping down to one of New England’s last real fishing ports.

“I said this place is unbelievable. Why don’t people know about this?” he said. “This is like Nantucket on the water, you know, the cobblestone streets, landscaping, the architecture. There were so many assets here.”

The group that hired Li Mandri to come to New Bedford, DNB Inc., wanted him to start a business improvement district, also known as a BID. After a few months of trying, Li Mandri couldn’t get enough support from property owners to form the downtown BID. His firm, New City America, later said that small property owners and their tenants “were uniformly opposed.” But Li Mandri decided to put down roots in New Bedford anyway.

He and his wife bought a second home in the city in 2015. A few years later, they bought a vacant building downtown and painted it a bright seafoam green. Today, their sons run a handmade clothing and jewelry store in the building, and their daughter works in one of the city’s addiction treatment centers.

Now, Li Mandri is trying again to establish a BID in downtown New Bedford. This time, he said he is no longer earning a consulting fee, or competing for a contract to run the BID, or even looking for a seat on its board. He said his goal is simply to bring more foot traffic to businesses here.

“When I said I was willing to do this pro bono, it’s because I really like this place,” Li Mandri said. “I like what the current character is of it. Do I think it can improve? Yeah, I think it can improve, and I think a lot of people think it can improve.”

Li Mandri has already set up 95 business improvement districts in the U.S., and there are thousands more BIDs in cities and towns across the country, including eight in other parts of Massachusetts.

The way a BID works is it charges mandatory fees from property owners in a specific commercial area. Then, it spends those funds on projects meant to benefit the businesses there. Many BIDs hire uniformed maintenance workers, who are sometimes called “ambassadors.” Others focus their resources on advertising campaigns, pitching the neighborhoods they serve as an attractive destination.

If the City of New Bedford approves the plan for the BID downtown, Li Mandri’s firm New City America estimates the fees will add up to an annual budget of nearly $240,000, with $45,000 of that total contributed voluntarily by the city government itself. The budget would be controlled by a nonprofit board of directors elected at a later date.

The plan itself does not lay out any protocols for electing the board, but Li Mandri has promised that a broad swath of the neighborhood will be invited to join: from developers and landlords to residents, artists and small business owners.

Advertisement

It turns out, though, that many of the artists and small business owners aren’t interested. On a recent Saturday night, many of them gathered for an open mic at Hewn, a clothing boutique downtown, to share some of their thoughts.

“Basically, I like to say it’s a hostile takeover of a shadow government,” said Jenny Newman-Arruda, who runs a downtown art gallery called TL6. “And we need to stop that because these people signed a lease saying they lived in New Bedford, not in Li Mandri land.”

In her remarks, Newman-Arruda said the BID will give New Bedford’s top landowners a more direct way of controlling what goes on downtown. She fears they’ll use that power to hire private security to patrol the district, and pressure people they consider undesirable to leave.

An Instagram account that shared a video of Newman-Arruda’s speech also recently featured a picture of Li Mandri’s face in an Instagram story. The word “EVIL” was scrawled across his forehead.

Not every critic feels this strongly about Li Mandri, but there’s a widespread sense that the BID could trigger the end of an era. For a long time, downtown’s been gritty and affordable. Creative people could rent cheap storefronts and start successful businesses like Cojo’s Toy World or Solstice, the local skate shop. These small, independent businesses have helped rebuild the neighborhood’s reputation as a place worth visiting. Now, many of those businesses hang bright yellow signs in their windows opposing the BID.

“It’s going to drive rents up for small business owners,” said Rhonda Fazio, who hangs one of the signs in the window of her multipurpose arts venue, to “where we can’t afford to stay here and they’re gonna replace it with people that can afford $4,400 rents.”

At Interwoven, across the street from City Hall and a chaotic bus station that doubles as a gathering place for the city’s homeless community, artists can hang their work, take classes, or color their clothes with turmeric and onion skins from Fazio’s collection of natural dyes.

Fazio, who often nourishes her visitors with snacks and tea, said she’ll probably close Interwoven if rents get much higher. Her bigger fear, though, is that the BID will make downtown New Bedford more like the generic, trendy neighborhoods that exist in every major city.

“You know, take away the creativity, and the character of the city — of people that have lived here, worked here, and also helped rebuild the city together.” Fazio said. “We all did that.”

The resistance to a business improvement district reflects a more general anxiety in the city about New Bedford’s future. Housing prices are rising fast. And longtime residents fear a new commuter train to Boston will make New Bedford more attractive to people with higher incomes. In their view, the BID might give downtown the facelift it needs to attract a Starbucks and a Banana Republic and high-priced doggie daycare.

The actual track record of business improvement districts is mixed. Tim Tompkins, a professor at New York University’s Marron Institute who studies partnerships between government and neighborhood-based nonprofits, said it’s hard to say anything definitive about whether BIDs cause gentrification.

“There’s not a lot of literature that looks at this holistically,” Tompkins said, “So, unfortunately, there’s not a lot of statistical answers that answer this question.”

Tompkins said he’s seen some BIDs accelerate gentrification, and others nurture and protect what a community already values. Tompkins said the direction a BID takes is determined by who’s on the board, and what their priorities are.

In New Bedford, Tompkins said, “There’s an active discussion and debate about that, which I actually think is really good for the setting up of one of these organizations.”

Li Mandri sees it differently. He said critics of the New Bedford BID are assuming the worst because they’ve been fed misinformation. He said the BID’s supporters have never planned on hiring private security or recruiting corporate chains, as some critics have suggested.

He also said people have been harping on distractions, like a 17-year-old FBI investigation that accused him of personally benefiting from a BID he set up in San Diego. Li Mandri never actually got charged with a crime, but he said people are circulating the report to turn public opinion against him.

In his close to 30 years of professional experience setting up BIDs, Li Mandri said he’s never encountered a business community as hostile to so-called outsiders as New Bedford’s.

“Have I ever had this type of opposition?” Li Mandri asked during a recent interview. “No,” he answered, “because I’ve never been confronted with people that put out so many half truths and lies.”

Despite the vocal opposition, Li Mandri said he has support from 61 percent of property owners within the business improvement district. That puts him just over the legal threshold Massachusetts law requires for a BID proposal to be presented for municipal approval.

But critics like Rose Miller, an accountant and commercial property owner with three buildings within the BID’s proposed boundaries, said Li Mandri was only able to hit that threshold by illegally “gerrymandering” the district to cut out as many opponents as possible.

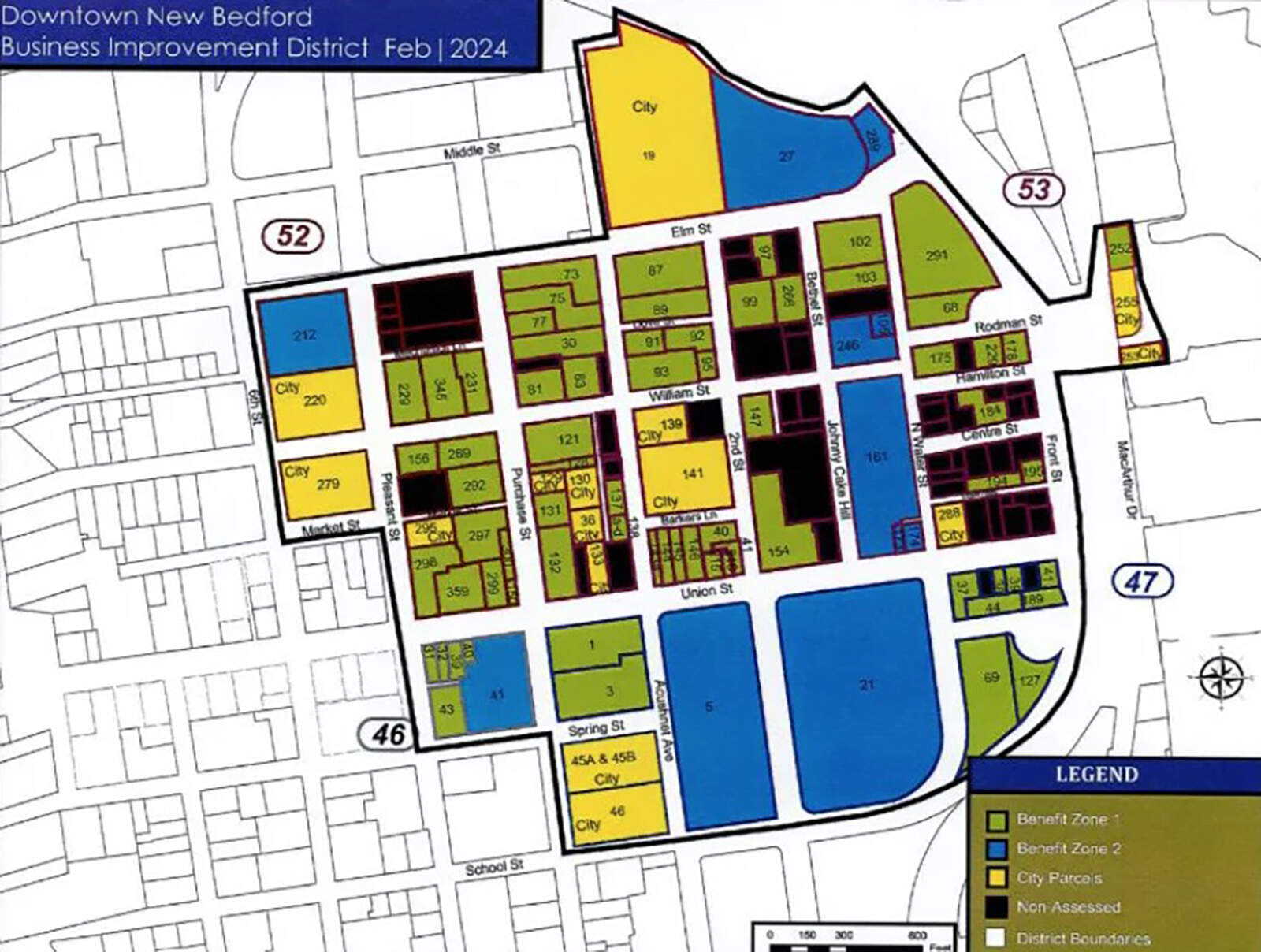

The BID’s plan effectively cuts small property owners — once the BID’s largest block of opponents — out of the district by exempting them from owing a fee. Li Mandri acknowledges the district might look like “a piece of Swiss cheese,” but he said his method for drawing up the BID’s boundaries and determining membership complies with the law.

The statute itself, Chapter 40O of the Massachusetts General Laws, states that a BID must be “a contiguous geographic area with clearly defined boundaries.” It also requires the signed support of “sixty percent of the real property owners within the proposed BID.”

The paperwork Li Mandri dropped off at City Hall has already been approved by the mayor’s administration. It’s now the City Council’s turn to accept or reject the business improvement district.

The BID is on the agenda for the council’s next Finance Committee meeting on Monday night, though a discussion about the legality of the district’s boundaries may delay the vote to a later date.

People on both sides of the issue say the eventual vote looks like it’ll be close – and they plan on showing up on Monday to make their voices heard.

The Public’s Radio in Rhode Island and WBUR have a partnership in which the news organizations collaborate and share stories. This story was originally published by The Public's Radio.