Advertisement

Busing's legacy in Boston, 50 years later

'We were fighting for our life': Former Boston Public Schools student, teacher reflect on busing, 50 years later

Resume

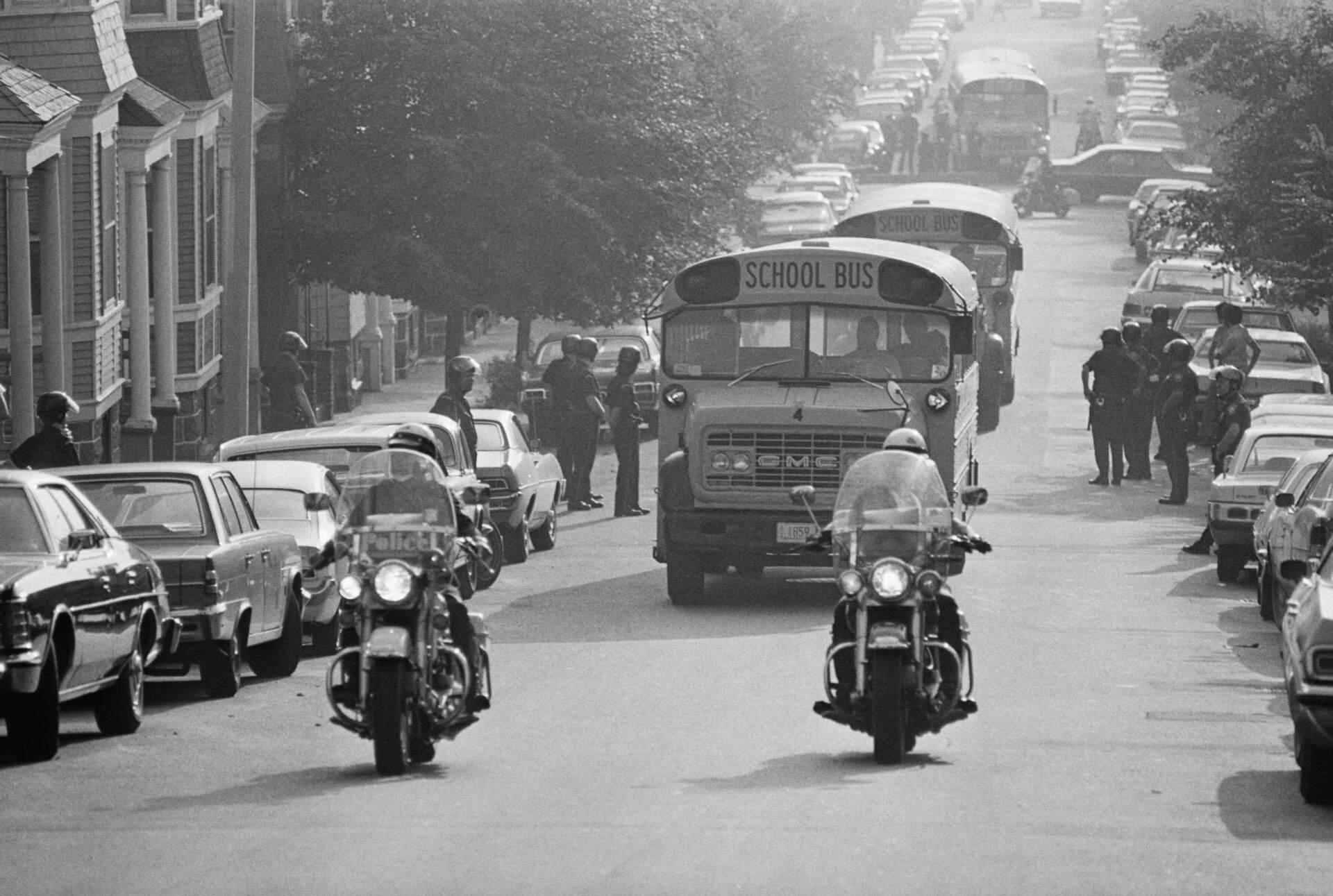

On June 21, 1974, federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered Boston Public Schools to desegregate. Thousands of students were bused to schools in different neighborhoods in an effort to more evenly distribute racial diversity across the district. White Bostonians responded with violent riots.

Nearly 50 years later, two people who lived through that history joined WBUR's Morning Edition to look back on what happened and how it still impacts us today. Leola Hampton was a student bused from Roxbury to South Boston High School, and Suzanne Lee was a teacher and principal in the district.

Interview Highlights

Highlights from this interview have been lightly edited for clarity.

On how she reflects on being a Black student bused to a predominantly white school:

Leola Hampton: "One of the things that resonates so much with me is that the Boston Public School Committee consciously made a decision not only to devalue Black children, but to prevent them from having an education. You can't get away from the fact that those decisions were made from a perspective of racism and anti-Blackness.

"In that time, there's this constant chatter about desegregation. There's this anger. Communities are picking sides. And that first day was horrific. The violence, the idea that that level of hate is being directed toward you — I don't think any child envisioned that."

"You can't get away from the fact that those decisions were made from a perspective of racism and anti-Blackness."

Leola Hampton

On being a first-year teacher assigned to Chinatown when the desegregation order came down, and then being transferred to Charlestown High:

Suzanne Lee: "Well, as a first-year teacher, you really don't know much what's going on anywhere else. It wasn't until the end of that first school year, parents came to me and asked me to read a letter for them. And the letter said, your child will not be coming back to the school next year. And immediately they looked at me and said, 'Where are they going?' I said, 'I don't know. It didn't say.' So that was my first introduction that nobody, at least in the Chinese community, knew what was going on.

"The day before school was to start, I got a call from some of the parent leaders. They said, 'Ms. Lee, we're not sending our kids to school tomorrow.' I said, 'Wait a minute, tomorrow is the first day of school. How are you going to do this?' [They] said, 'We'll find a way and we know what to do, but we are not going when they would not guarantee us safety and communication with us.'

"My assignment came a few days before school started. So I was very nervous the next day since I volunteered to ride the buses with the kids. Through that whole journey, I see lots of people at the bus stop and nobody got on the bus except for two African-American children."

On having police escorts during busing:

Lee: "I rode the bus all the way to Charlestown and we would wait there for police escorts. And by that time, the two students were getting very nervous. And I have to stay calm because I can't be nervous because I have to be strong for them. We saw a lot of people on the street when we passed by Charlestown High School, but nobody threw rocks. But we had police escorts for at least two years."

Hampton: "Every day for about a year, every school bus had the motorcycle police on each side — one in the back, one in the front. Each morning we went through metal detectors, every classroom had a police officer outside and the cafeteria was lined with police officers throughout.

"I think as a kid, you're trying to understand that the mere presence of you being at a school would require police protection. And the minute you reach a certain part of South Boston, it seemed as if every family member, from the youngest to the elderly, was outside making sure that you felt that you're not wanted here. Being surrounded by that level of hate, even to this day when I think about it, it's definitely hard to conceptualize."

"Even 50 years later, we have to find ways to really to understand each other as people — not, you're with this group or that group. And that's where the healing comes from."

Suzanne Lee

On finding common ground with other students and teachers who were bused:

Hampton: "[Recent discussions are] the first time I'm actually having conversations with white kids that were there. Now that we're having this exchange, we're understanding that the school system and our politicians and government played us against each other.

"You've got two poor neighborhoods — South Boston and Roxbury. You've got 400 years of stereotypes and racism and all these images of what Black people are. So of course, they're saying, 'I don't want these children in my neighborhood.' On the flip side, we were fighting for our life when we got to South Boston. So, the whole story is horrific, and the sad part is that I never want people to deviate from the fact that at the epicenter of all of this is this racist system. I mean, you can go back to the first schools that were created here in Massachusetts. At that time, [they decided, we'll have] schools, but we can't have Black children in them."

Editor's Note: This video essay includes the use of a racial slur.

Lee: "You know, so much happened during that time, that all we could do is just react to the situation. And even 50 years later, we have to find ways to really to understand each other as people — not, you're with this group or that group. And that's where the healing comes from."

On the lack of resources for students who were learning English:

Lee: "I still vividly remember that first year. The white teacher obviously did not offer any support, except to keep taking it out on the children — 'Speak English, speak English! You're here now.' I said, 'Wait a minute. If you don't allow them to say anything in Chinese, that's telling them not to say anything at all.' And they would be punished, particularly in the lunchroom. They'd have to pay a quarter every time they used Chinese among themselves.

"But, when you have that kind of atmosphere, where the adults don't act in the way that you show the empathy and also show understanding, children see that. And they shut down. So it was a horrific time."

On the microaggressions students still face today:

Hampton: "So when my granddaughter goes to school and she wears her hair in braids, they're asking her a million questions, [like] 'Do you have to get up every morning and redo all the braids?' And I just find it interesting that she has no questions for them as to how you do your hair. So, it causes our children to bear the burden of a system that continues to have all of these different microaggressions that they have to deal with.

"I wish she could just go to school and do whatever kids do in the fifth and sixth grade. But she has to bear the burden of them making jokes. She said they did a program on Bob Marley and some of the boys in [the class], they're laughing and they're making monkey jokes because that's how they see Black people in 2024. Children are coming to school, white children, continuing to make jokes about Black people. Who's teaching these kids?"

"Children are coming to school, white children, continuing to make jokes about Black people. Who's teaching these kids?"

Leola Hampton

On where BPS stands on its goal of integrating schools:

Hampton: "I think they still have a long way to go. There are so many people. There are so many different avenues that are pushing them to do the right thing. But again, if we don't put that element of history in there as part of the learning, I think we'll continue to fall short of the goal."

Lee: "I think some good came out from the desegregation. The court order mandated that you have to have certain percentage Black teachers and then later added on [other teachers of color]. Well, BPS still struggles with that, not even meeting that 30%. And you look at the students who are in BPS now — we're 80% students of color. So why is that so important? Because of that history. I'm not saying that white teachers cannot teach that history. Yes, they can. But who better to be able to have that empathy and that connection with our students? But the system itself is not doing enough.

"So you ask yourself, what is the point of all 50 years of that trauma? So has BPS come a long way? In some ways, but then in other ways, we're right back to where we started."

Hampton: "Still got a long way to go."

This segment aired on June 18, 2024.