Advertisement

BUSING'S LEGACY IN BOSTON, 50 YEARS LATER

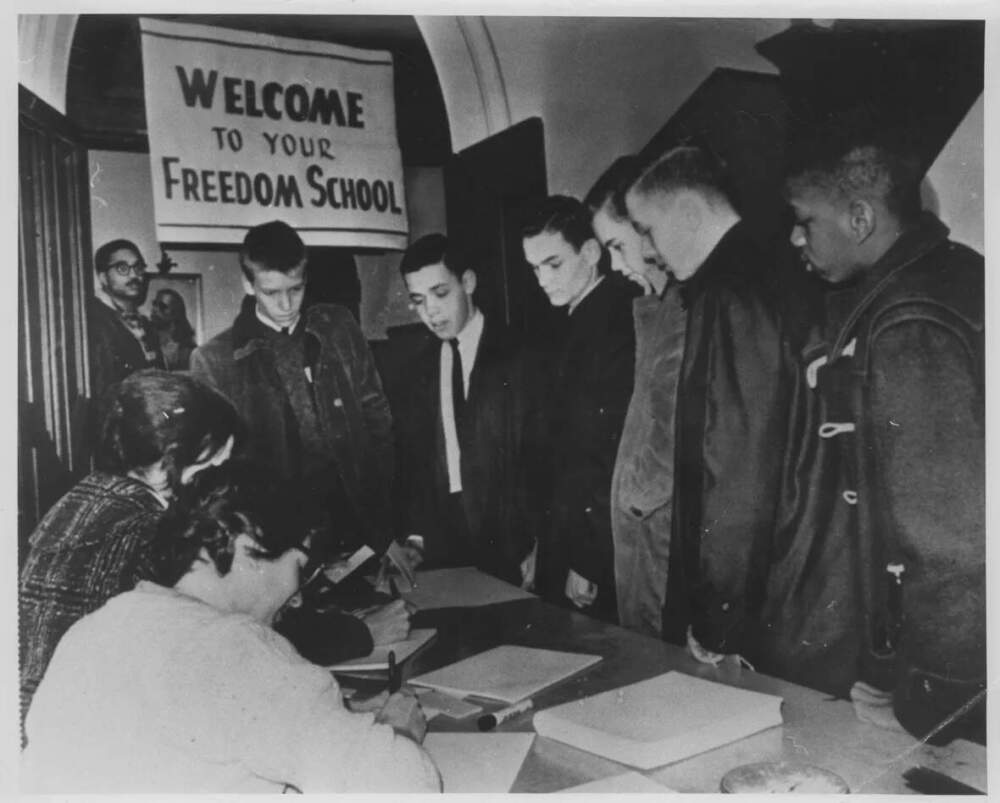

The beautiful vision of Boston’s Freedom Schools

Resume

Boston Public Schools are in trouble.

As an educator, when I look at the problems they are facing during the current school year, I see overcrowded and underfunded inner-city school buildings that face declining enrollment for Black students, low attendance, low standardized test scores and low graduation rates compared to better funded schools in surrounding areas. I can’t help but wonder how we’re still facing the same issues that have plagued Boston’s schools for decades.

The bigger question is this: Why do these problems persist when local civil rights-era visionaries already showed us how to create a more dynamic and progressive future for all students? Why have their work and names all but completely faded from memory in just 60 years?

I grew up in the South End/Lower Roxbury neighborhood, one of the main sites of the Boston Freedom Schools in 1963 and 1964. Freedom Schools were part of the Civil Rights Movement, where leaders set up free, temporary schools for Black students that provided political, civics and academic instruction. The brainchild of Charles Cobb, a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee activist, the Boston Freedom Schools were a response to the Boston School Committee’s refusal to address education inequity that local Black residents faced.

While walking around my neighborhood a few months ago, I was gutted to see that numerous historic sites where Black activists and civil rights leaders once met and organized had been demolished and replaced by luxury condominiums. This includes the community center Harriet Tubman Home, the New Hope Baptist Church and the Concord Baptist Church. The former Jorge Hernandez Cultural Center is gone and still waiting to be replaced. Outside the privately owned 451 Massachusetts Ave., there is no signage to indicate that it was the site of the original NAACP Boston Branch.

This was once Boston’s most diverse neighborhood between the 1940s and 1960s, home to Black, Latinx, Asian and White denizens alike. Many were poor, working-class railroad pullman porters, musicians and students. Legends lived here, including entertainers such as Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Sammy Davis Jr. and Quincy Jones, as well as civil rights titans such as Malcolm X, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King.

Even though these venerated old buildings are disappearing, it is imperative we preserve their legacy, including the important lessons learned from the Boston Freedom Schools.

__

As Boston’s Black and Latinx populations increased dramatically in the 1960s, inner-city residents banded together and began to assert themselves. It was clear Boston Public Schools were extremely segregated and unequal. Over time, Black and Latinx parents became increasingly vocal, demanding solutions for the substandard facilities and low-quality education their children were subjected to.

The school buildings themselves were ancient and in serious disrepair; the oldest buildings that served as schools for these children were constructed in the late 1800s. In the previous year, The Boston Globe published a report stating that only 10% of Boston Public Schools teachers were Black, despite 20 schools having majority Black students, 13 of which reached 90% Black student enrollment. An independent study conducted by Paul Parks of the Boston NAACP revealed students in Boston Public Schools were performing below the national average in English, math and reading, with Black students scoring even lower. The study concluded that when it came to its Black students, Boston Public Schools “compiled an uninterrupted record of negative progress.”

Advertisement

By 1963, Boston’s Black community had reached a breaking point when it came to the sorry state of its children’s education. Ahead of the 1963-64 school year, the Boston NAACP petitioned the Boston School Committee, Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination and the Attorney General’s Advisory Committee on Civil Rights to address segregation in Boston Public Schools.

According to collected minutes from the June 11, 1963 Boston School Committee meeting, then-Superintendent Frederick Gillis insisted that “school imbalance” was a direct result of residential patterns, and “school district boundaries are not based on ethnic or religious factors.” Boston School Committee Chairwoman Louise Day Hicks refused to acknowledge that anything was wrong with the facilities, education or treatment of Boston’s Black and Latinx students. For many Black and Latinx parents, civil rights leaders, activists, and community organizers, this was the last straw. It was time to take action. The Boston Freedom Movement would take matters into its own hands.

It was the communal network, organizing tactics and collaboration between Boston’s Black churches and civil rights leaders that made it possible for inner-city support groups to unify around a common cause. Community leaders, activists and clergy collectively formed the Freedom Stay-Out Committee.

While we saw school boycotts and stay-out days also occur in other cities for similar reasons, only Boston aimed to improve the education, environments and curriculums for the entire public school population.

The two co-chairs of that committee were Noel A. Day and Reverend James Breeden, who both organized Boston Freedom Schools. Day was a Dartmouth-educated New Yorker who moved to Boston to be a social worker, then later became a community organizer in Roxbury. Breeden was an Episcopal priest at the St. James Church in Roxbury, who was also an activist and community organizer. He was one of the 15 Freedom Riders arrested in Mississippi in 1961 for entering a segregated restaurant at a rest stop during a bus ride with a mixed group of Black and White clergy. The two men were co-chairs of the Freedom Stay-Out Committee, and they both worked closely with the Boston branch of the NAACP, which was based in South End/Lower Roxbury.

Two weeks later, after another fruitless Boston School Committee meeting, 8,260 students skipped class and 3,000 more attended classes at one of the Freedom Schools. There was also a big rally staged at St. Mark’s Social Center, with several public speakers, including Boston Celtics captain Bill Russell and comedian and civil right activist Dick Gregory.

The curriculum taught at these schools, which ran from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., was created by Day and his then-wife Peggy. Around the same time period, other cities — including Chicago, Detroit, New York, Milwaukee and Cleveland — also had stay-out protest days and organized their own Freedom Schools. But only Boston implemented “reciprocal integration,” a concept developed by the Days, which recommended introducing White students to Black schools and vice versa. Moderated discussions between White and Black students broke down barriers and helped dispel myths. When the Freedom School attendees learned about Black history and African culture, they gained a sense of belonging and pride. It was the first time they were taught Black history or asked their opinions and thoughts in a classroom.

While the first Freedom Stay-Out Day was a modest success, the follow up in February 1964 redoubled in both scope and scale, and made it impossible to ignore. The renowned Mississippi Freedom Schools organized later that year would also go on to adopt the curriculum developed by the Days.On Feb. 26, 1964, over 20,000 students didn’t go to class in Boston Public Schools facilities, while more than 10,000 students attended Freedom Schools at 35 designated sites around the city, which were staffed with 2,000 volunteers. Far better than a boycott on education, participating students enjoyed a rich day of learning and sharing. The Boston Freedom Movement received support from White suburban educators in addition to nearby Boston University, Simmons University and Boston College. Those students who didn’t attend class that day accounted for more than 22% of all students enrolled in Boston Public Schools for the 1963-64 school year.

The fight for quality education, safe school facilities, new books, and more Black teachers, support staff, principals, and headmasters was underway. Participating White children were bused to Freedom Schools to experience the Days’ reciprocal integration model to foster understanding between the Black and White students. WGBH Boston dedicated hours of live programming from one of the main Freedom School sites, the St. Mark’s Social Center, and broadcasted the Boston Freedom Movement’s mission statement for the entire city to hear.

As Peggy Day told the students who chose to attend Freedom Schools that day, “We are staying out of school to tell the School Committee and the community that we don’t want inferior schools. We want equal schools. Some parts of the program today will give us a taste of … the things we should learn in the public schools.”

While we saw school boycotts and stay-out days also occur in other cities for similar reasons, only Boston aimed to improve the education, environments and curriculums for the entire public school population. When students shared their collective and individual frustrations in moderated sessions, they took in one another’s unfiltered truths. One of the biggest hurdles to bridging gaps of understanding and relatability between Black and White students was that they were rarely in contact with one another, and White children were taught to view their Black counterparts as inferior.

As a lifelong Black Bostonian and resident of the South End/Lower Roxbury, it fills my heart with pride knowing my neighborhood served as a hotbed of activism and was the central location for racial progress, self-determination and inclusion.

The 1964 Boston Freedom Schools occurred about six months before the creation of Operation Exodus, which bused Black students from Roxbury to Beacon Hill’s Peter Faneuil School. They also were in place over two years before the better known Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO) transported Black and Latinx students from Boston’s inner-city to better funded schools in Newton, Brookline, Wellesley and Lexington during the 1966-67 school year. These well-meaning programs had no plans to integrate the bused students with their White counterparts or bridge gaps of understanding between them. Because the bused students were not set up for success, this made for a tumultuous transition for all students and undercut the goal of fostering understanding and respect.

While METCO succeeded in physically taking Black and Latinx students to better funded schools with newer buildings, more amenities and top-tier education, they failed to help these city kids feel welcome in suburbia. In 1969, Noel Day critiqued programs like METCO in his essay “The Case for All-Black Schools,” which was published in the Harvard Educational Review. He wrote that “a program that moves children out of a Black community into a White community without reciprocal action may be little more than a clear object lesson that denies the worth of the Black community.” The Days’ model was superior because it considered the needs of both student populations and addressed the importance of acknowledging their collective experience.

Though I was born after this happened, I directly benefited from these activists’ efforts. I attended neighborhood elementary schools such as the William Blackstone Elementary in the South End/Lower Roxbury’s Villa Victoria housing development, which served Boston’s burgeoning Latinx population, and the Josiah Quincy School, which was in Boston’s Chinatown. Without the grassroots work, activism and reform of folks like the Days, Breeden and community activists like Mel King, I would not have been able to attend school in new buildings, with Black and Latinx teachers that made me feel seen and acknowledged. Representation matters, and the empowerment I felt as a young child followed me well into adulthood.

As a lifelong Black Bostonian and resident of the South End/Lower Roxbury, it fills my heart with pride knowing my neighborhood served as a hotbed of activism and was the central location for racial progress, self-determination and inclusion. At the same time, I am pained by the present landscape and its lack of the same advocacy, activism and community-led action that once uplifted an entire generation of Black and Latinx inner-city students.

The children deserved better 60 years ago, and they deserve better now. I write this with the hope that more people will learn this important history, celebrate its beautiful vision and continue the fight to make it a reality for all.

This story was originally published by The Emancipator and is part of an editorial partnership between WBUR and The Emancipator on the 50th anniversary of a federal judge’s ruling that led to busing of schoolchildren in Boston.

This segment aired on June 20, 2024.