Advertisement

Busing's legacy in Boston, 50 years later

As Boston pursues 'hub' model, city battles memories of segregated neighborhood schools

Resume

In the mid-1960s, Lyda Peters taught first graders at The Quincy Dickerman Elementary School in Dorchester, then a low-income, predominantly Black neighborhood. Peters was one of the few Black teachers.

At that time, Boston Public Schools mostly sent kids to schools close to where they lived. Zoning and residential segregation led to racially imbalanced schools. In 1965, just 12 of the 486 kids enrolled at Quincy Dickerman were white, according to a state Racial Imbalance in Education advisory committee report.

Most years, Peters said, the district squeezed 30 to 40 students into her classroom.

"One year I had 50 first graders," she said.

Once the kids were crammed into class, she said, they were given old textbooks and outdated resources, like an assessment of a first grader's reading ability. The only test available in the school was from 1949.

One day, she and two other teachers found a Black student in a closet. The 7-year-old had been stuck in the space as a form of discipline by another teacher, who then forgot she was in there. It's a moment that's stuck with Peters to this day.

"I mean, that’s not how you treat kids," Peters said. "All I could think about was, 'Her mom must be going crazy.' "

In her 2017 doctoral dissertation, Peters included this anecdote, writing how "this experience, unfortunately, was typical of how too many Black children were treated in the Boston schools."

It was conditions like these, and the inferior education for students in majority-Black schools, that led to a federal lawsuit against the Boston School Committee in 1972. Black parents wanted their children to have the same educational opportunities as other school kids in Boston.

Advertisement

What they got was a court-ordered busing mandate that took thousands of kids on long commutes out of their neighborhoods, often into hostile environments. Black kids were bused to majority white schools, white kids to then-majority Black schools.

To Barbara Fields, a now-retired teacher and administrator for the Boston schools, who taught first grade at the now shuttered Taft Elementary School in Brighton in the 1970s, the necessity of the court case reflected the reality of neighborhood schools at the time.

"It was about access to a better or a quality education. It was around the inequities," she said. "It wasn’t about that anyone wanted to send their kids out of the neighborhood someplace else. It was about wherever the quality of education was, folk wanted to have access to that."

Federally mandated busing ended in 1988. In order to avoid the segregated enrollment patterns that the old neighborhood school assignment process created, the district switched to using a system that relied on parent choice. The model has evolved over the years, but today Boston uses an algorithm that assigns kids based on several factors including family preference and where in the city they live.

Though parents now get more say in where their kids go to school, many students still face significant commutes to get to class each day. In a given day, Boston buses traverse more than 43,000 miles of road to bring kids to school.

"I think what we’ve heard from parents is that they want options closer," said Boston Public Schools Superintendent Mary Skipper. "They just don’t want to have to travel across the city to get to that solution."

"It wasn’t about that anyone wanted to send their kids out of the neighborhood someplace else. It was about wherever the quality of education was, folk wanted to have access to that."

Barbara Fields

That’s why Skipper says she's a big proponent of a relatively new "hub school" model. Schools that use it can offer more academic and enrichment opportunities to students than a regular school's budget would allow. That's made possible by partnerships with city businesses and nonprofits like the YMCA.

For example, the Jeremiah Burke High School partners with Franklin Cummings Tech and Bunker Hill and Roxbury community colleges for early college or afterschool opportunities. Northeastern University offers tutors, according to the school's web site.

Other hub school sites offer free swim lessons through the YMCA or music instrument lessons.

There are currently 14 such sites in Boston, across all grade levels. Many are situated in Roxbury and Dorchester, home to a high concentration of Black students.

Jessica Tang, outgoing president of the Boston Teachers Union and incoming president of American Federation of Teachers Massachusetts, said attending a hub school isn't mandatory. Rather, the goal is to make it so that parents want to go to the schools that are close to them.

Still, she said, getting community buy-in for the idea hasn't been easy, especially since the original name of the hub school model was "community schools." That's due, in part, to lingering bad memories of the neighborhood school assignment system from Boston's pre-busing era.

"We would go out into the community and we’d talk about 'community schools' and immediately people would say 'no, we’re not going back to neighborhood schools right now,' " Tang said. "We intentionally created the name 'hub schools' because we didn’t want it to be confused with neighborhood schools."

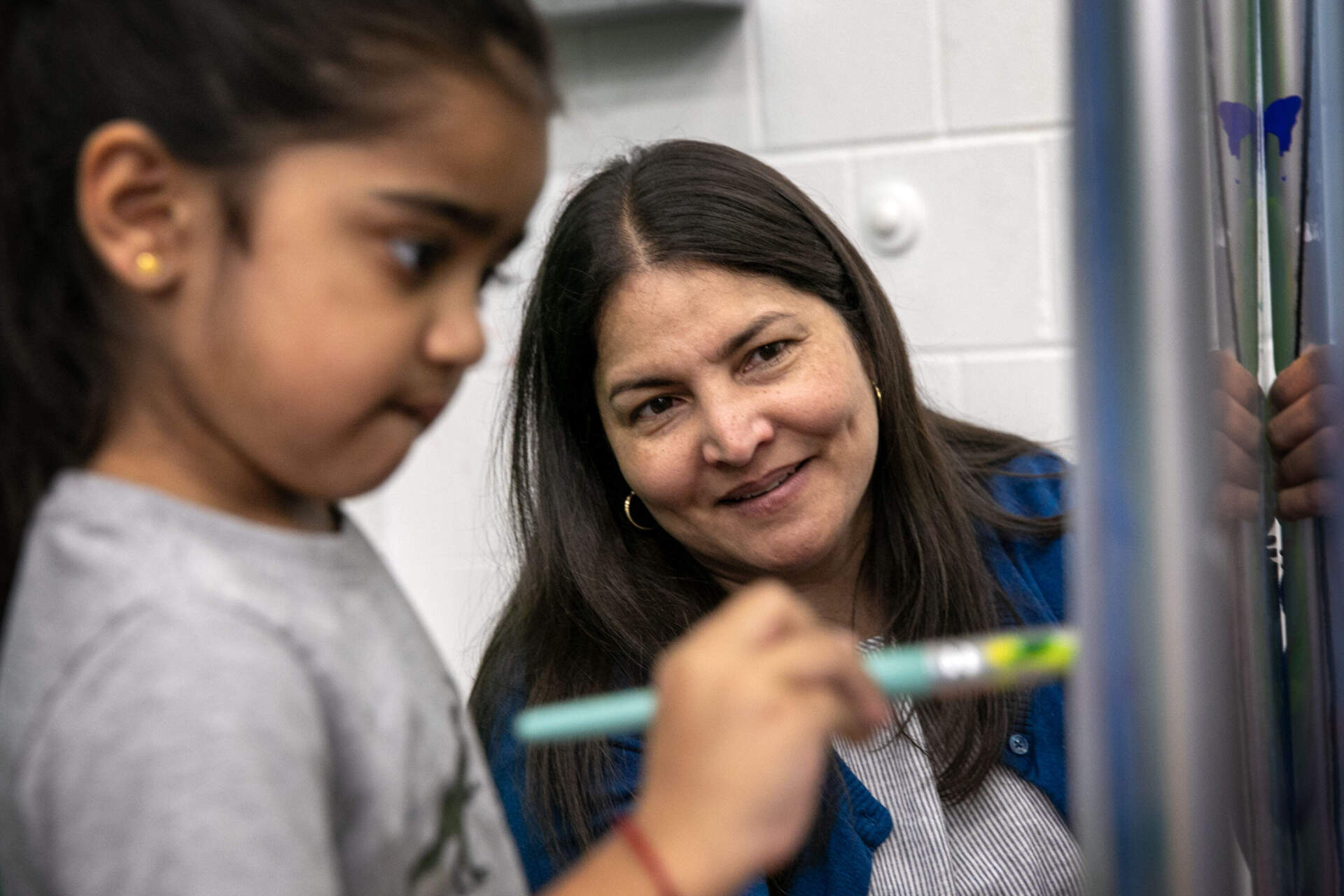

The Mario Umana Academy, a K-8 school in East Boston that serves a 93% Hispanic student body, reflecting the community around it, was among the first schools to try out the hub model.

Umana has forged over 60 partnerships with nonprofits over the last two years, according to hub school coordinator Lilliana Arteaga.

East Boston Social Centers helps the school offer a play group for neighborhood families. Three days a week, the organization hosts educational activities and provides toys for parents and caregivers inside a classroom space at the elementary school.

Another partner, the Community Music Center of Boston, provides free weekly hour-long music lessons with a variety of instruments. That’s allowed Umana staff to support an after-school student band.

Boston Partners in Education provides academic mentors. And the Boston Nature Center helps educators create science lessons using the natural environment outside the school.

School leaders believe all of these partnerships can foster a sense of community among students and families and hopefully lead to better academic outcomes.

"The goal around hub is to really saturate and create lots of opportunity," Skipper said, adding that part of the planning process is looking at which "good and healthy [partnership] choices" exist within the city's regions.

But the vast disparities among Boston’s neighborhoods still present a challenge. Fields, now a community and education advocate in Boston, said the city is still a long way away from making sure every child — especially poor kids and kids of color — have access to a quality education.

School closures and mergers in areas like Dorchester disproportionately impact students of color, Fields said, and certain neighborhoods in Boston don't have as many third-party resources to offer enrichment activities. In the last five years, the district has closed or merged 10 schools including three in Roslindale and two in Dorchester, and has two additional school mergers planned in the next few years.

"Mattapan is not the same as the North End or as West Roxbury," Fields said. "Until we can really deal with equity across the city, I just don’t think that we’re at a point where we’re real serious."

It's still too early to tell, for instance, whether the model will lead to improved attendance, test scores or higher graduation rates. But a 2020 RAND Corporation study shows school districts outside of Boston that have implemented similar "community school" models have shown improvements in those areas.

But for now, community feedback at the new hub schools has been good. Which is why the district plans to expand the model to other schools by hiring new hub school coordinators who can facilitate community partnerships.

If that’s successful, then going to an enriching school in Boston may no longer require a long commute across the city.