Advertisement

Commentary

Boston theater moves from Modern love to meeting a new moment

Paul Daigneault’s decision to step down as the artistic director of SpeakEasy Stage Company marks the end of an amazing era in Boston theater, one in which Boston grew from being a national backwater to become an artistically thriving theater community that could hold its own against other cities its size. It’s an era that I feel privileged to have covered as theater critic at the Boston Globe and critic at large at WBUR between 1995 and 2020.

The commercial downtown scene had changed from being a preeminent Broadway tryout town to presenting Broadway road shows. The Huntington Theatre Company and the American Repertory Theater were established high-quality theaters in the mid-‘90s, but the midsize scene was uninspired, to say the least. Three theaters and their artistic directors were about to change that: The Lyric Stage Company of Boston under the late Spiro Veloudos, the New Repertory Company under Rick Lombardo and SpeakEasy, founded and led by Daigneault. There were important women in that era’s growth of Boston theater, too, such as Carmel O’Reilly, Mimi Huntington and Kate Snodgrass.

So what was it that Daigneault and the others brought to the table?

- A keen eye for Boston’s theater talent – playwrights, actors, directors and designers — and where they could best make their mark artistically.

- A prioritization on modern and contemporary work over classical productions.

- A development of an ecosystem in which large, midsize and small theaters worked together instead of alone.

- A determination to bring the best plays from America, the UK and Ireland (and beyond in ArtsEmerson’s case) to Boston.

Additionally, the midsize theaters filled voids left by the larger ones. While the commercial theaters in the late ‘90s were bringing in a steady procession of Eurotrash musicals from Andrew Lloyd Webber and Schönberg-Boublil (“Les Miz,” “Miss Saigon”), the midsize theaters were reviving what was then the less commercial work of Stephen Sondheim. Veloudos’ “Assassins” in 1999 at the Lyric boldly showcased Boston’s singing talent and a daring new direction for the theater as well as Veloudos’ special talent for Sondheim. Dagneault’s production of “Passion” in 2002 introduced many theatergoers to the spectacular singing of Leigh Barrett.

Many of the artistic directors were champions of modernism, none more so than the recently deceased founder of the American Repertory Theater, Robert Brustein, who provided a steady diet of Brecht, Chekhov, Strindberg, Pinter, Beckett and their sons and daughters like David Mamet, Sam Shepard, Adrienne Kennedy and Suzan-Lori Parks. His counterpart at the Huntington, Peter Altman, was championing the work of two great playwrights, Tom Stoppard and August Wilson.

That still left a huge void. Neither the Huntington nor the A.R.T. wanted to have anything to do with three of the great playwrights of the time -- Edward Albee, Caryl Churchill and Tony Kushner. Veloudos directed memorable productions of both Albee and Churchill. Daigneault directed a lovely production of Kushner and Jeanine Tessori’s “Caroline, or Change” while Boston Theatre Works presented Kushner’s “Angels in America” and “Homebody/Kabul.”

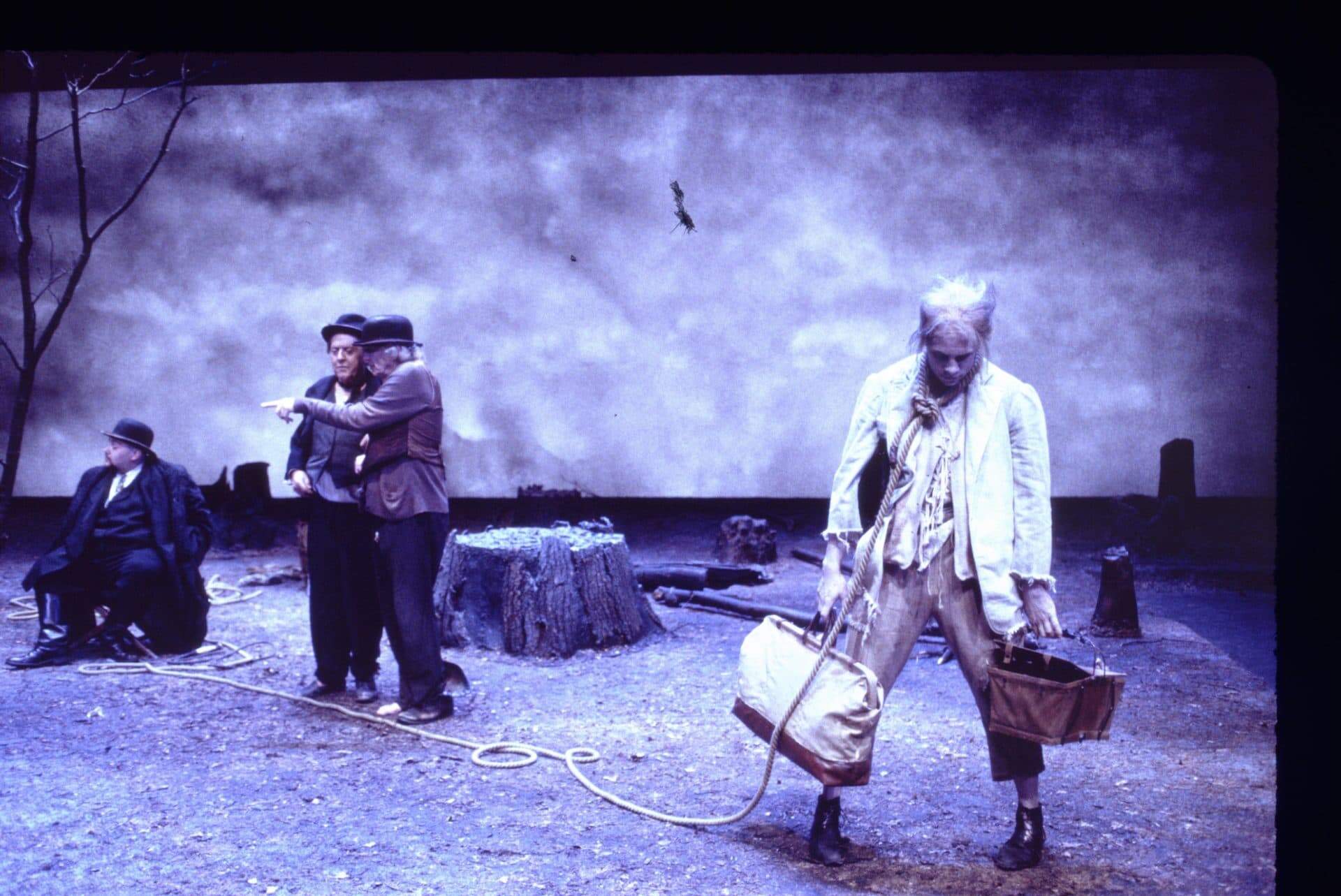

If the ‘90s was a hotbed of modernism, that aesthetic has changed today. The modernists met the moment in the 20th century with plays that questioned humanity’s place in a universe where God was either silent or nonexistent. The two world wars and the prospect of nuclear annihilation were proof enough. Playwrights tended not to meet these issues head-on, but were often oblique or absurd and railed against easy interpretation. Beckett, for example, hated readings of “Waiting for Godot” that posited the never-present Godot as a stand-in for God. While Albee and Pinter were committed leftists, it’s hard to find strong evidence of politics in most of their plays, at least at first blush.

There was also a more representational or realist side to modernism that included Clifford Odets, Arthur Miller, Lorraine Hansberry, August Wilson and, for the most part, Kushner.

Wilson, Anna Deavere Smith and Kushner are key transitional figures to where we are today, with Hansberry reigning as the godmother. If the great modernist playwrights were primarily concerned with a spiritual void and a soulless, materialist culture that crushed the human spirit, today’s leading, young playwrights are more concerned with identities that are crushed within a more ethnocentric and gender-based framework. Wilson and Kushner are rooted in modernism, but their outlook is more straightforwardly political than, say, Eugene O’Neill or Albee’s.

Call the theater of the 21st century what you will – progressivism, for starters. But once again Boston is something of a hotbed for it, particularly in the wake of #MeToo and the murder of George Floyd. If David Wheeler’s Theater Company of Boston got the Modernist ball rolling locally between 1963 and 1975, it was Company One Theatre that led the way in breaking away from an aesthetic that was largely white, male and Eurocentric. Current artistic directors Shawn LaCount and Summer L. Williams have been there and preaching the gospel of diversity from the beginning.

Advertisement

Company One began, appropriately enough, at the turn of the century. Profiling them for WBUR in 2015 I said, “When you start ticking off some of their recent big hits -- Annie Baker’s “The Aliens”and “The Flick;” Kristoffer Diaz’s “The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity;” Walter Sickert and the Army of Toys in “Shockheaded Peter;” and, wait for it, “We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915” -- you’re talking about some of the most thrilling local theater in New England during the past five years.”

“We Are Proud” was copresented by ArtsEmerson, where founder Rob Orchard stretched his A.R.T. aesthetic to include more political theater and his successors tipped the balance even further from modernism to works about social justice. Diane Paulus, Brustein’s eventual successor at A.R.T., has also moved in that direction as Tennessee Williams has given way to V (formerly known as Eve Ensler). And almost everyone in the Boston area is looking to work with the excellent Black theater company, the Front Porch Arts Collective.

Many theaters in Boston are now uniting to present Mfoniso Udofia’s nine-play “Ufot Family Cycle,” following three generations of a Nigerian-American family.

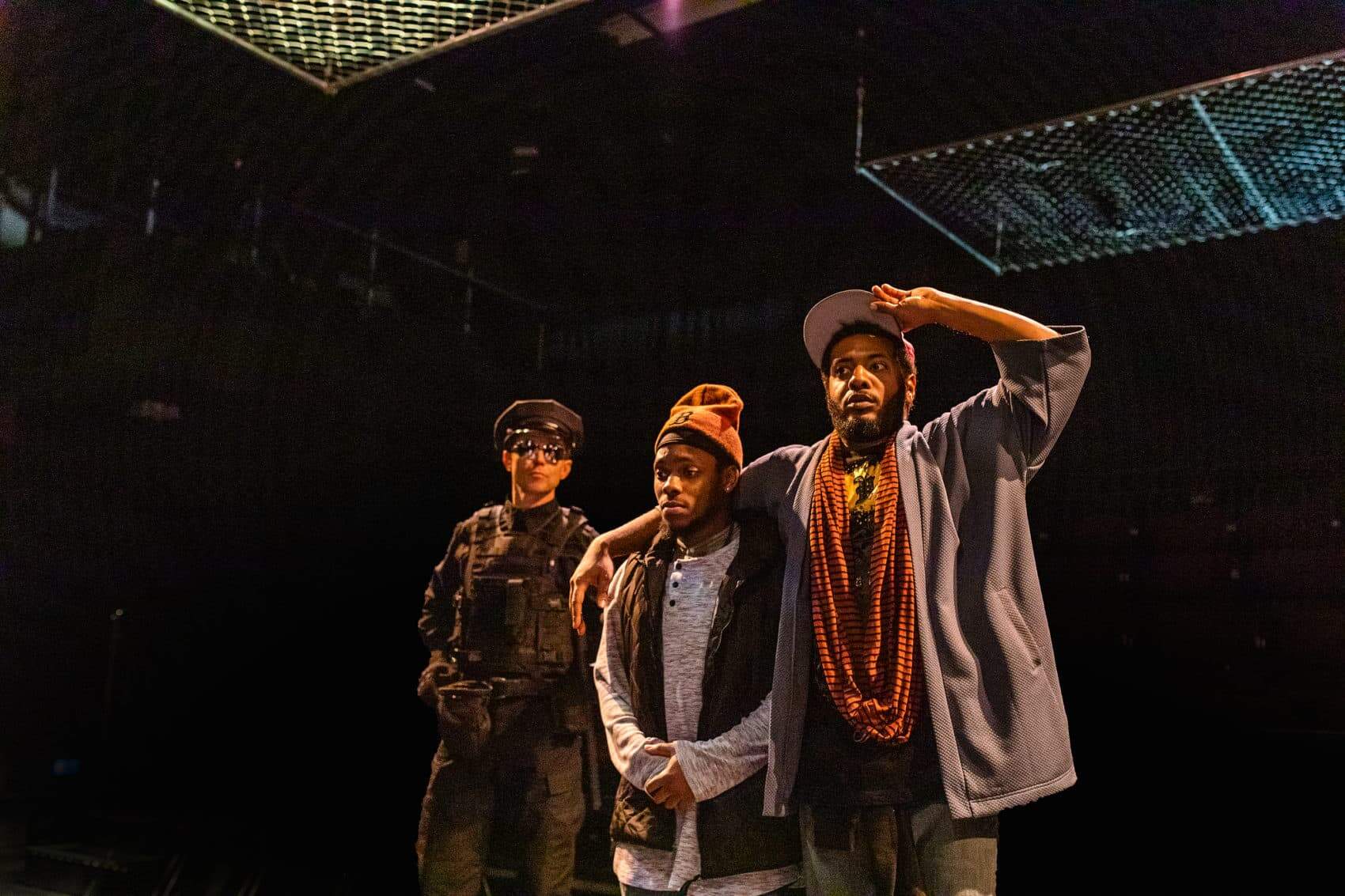

Daigneault was always on board as well. His programming has been a heady mix of most schools of adventurous contemporary theater, including musicals, championing everyone from Kushner and the scabrously soulful Stephen Adly Guirgis to Lucy Kirkwood’s “The Children” (which contains multitudes when it comes to various artistic schools) and Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu's “Pass Over,” a riff on “Waiting for Godot.”

Other Boston theaters have also followed suit, much more so than, say, the Berkshires, Wellfleet or New York, to name nearby theater sites that did not throw out the modernist baby with the bath water.

Philosophically, perhaps the main difference between modernism and progressivism is that moral ambiguity has been exchanged, for better or worse, for moral certainty. “Waiting for Godot” is subject to all kinds of interpretation, including a political reading that draws on Beckett and his wife-to-be Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil hiding from the Nazis in WWII France. There’s really only one interpretation of “Pass Over” in which the Black counterparts of Beckett’s characters are victims of white racism.

Similarly, the modernist playwright John Patrick Shanley leaves open whether the priest is an abuser in the aptly-titled 2004 play “Doubt.” In fact, Brian F. O’Byrne, who played the priest, and Cherry Jones, who played the nun accusing him, talked about how they would subtly change their portrayals depending on how they sensed the audience was leaning. They would move in the opposite direction.

In Kimberly Belflower’s “John Proctor is the Villain,” which received a strong production at the Huntington Theatre Company under artistic director Loretta Greco, there is no doubt about it. A teacher explicating Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” seduced one underage student and is in the process of coming on to another.

I’m not here to say that modernism is artistically better than progressivism or vice versa, although politically-motivated theater often falls by the wayside historically. Starkly political Black playwrights of the past like Ed Bullins and Amiri Baraka are not often produced today despite being highly regarded in their time. We tend to think more highly of the nuanced Arthur Miller or Eugene O’Neill than the more overtly political Clifford Odets.

One could counter that it’s as important, if not more important, to meet the moment than to write for the ages. It isn’t, though, an either/or proposition. Just look at all the wonderful revivals of Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” or Kushner’s “Angels in America.”

Boston hasn’t completely turned its back on modernism. Some of the Brustein aesthetic lives on with the Arlekin Players. The Huntington is producing a playwright they’ve championed from the beginning, Tom Stoppard, next season. Interestingly, though, it’s the modernist master’s latest play, the highly-regarded “Leopoldstadt,” which might be his only play to be primarily concerned with ethnic identity – Stoppard’s long-suppressed embrace of his Judaism.

There is, then, plenty of room for overlap. In the end, the best plays that meet the moment and the great ones that met a previous moment have one thing in common – they’re well-told tales that provide a resonance with audiences that other artistic mediums are hard-pressed to match — whatever the “ism.”