Advertisement

Review

'Janet Planet' and 'Daddio' mark the arrival of serious cinematic talents

In a bizarre quirk of timing, two movies by female playwrights making their directorial debuts open in the Boston area this weekend. Garnering rave reviews on the festival circuit since last fall, “Janet Planet” is the first film from Amherst’s own Annie Baker, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2014 for “The Flick,” a three-hour drama about a run-down Worcester movie theater that was like “The Last Picture Show” for an age of indifferently maintained multiplexes. Christy Hall’s “Daddio” isn’t arriving with nearly as much advance buzz, but it’s a small miracle of a movie, adapting a two-character conversation to enormously affecting ends. Both films announce the arrival of serious cinematic talents.

A portrait of a mother through the eyes of her daughter, “Janet Planet” is an evocative memory piece during which an entire universe is revealed in dribs and drabs. Eleven-year-old old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler) lives with her single mom Janet (Julianne Nicholson) out in the Pioneer Valley of western Massachusetts. Uncommonly close, the two still usually end up sleeping in the same bed at night, where mom is prone to oversharing personal matters that her daughter probably didn’t need to know about just yet. The film takes place over the summer of 1991, after Lacy demands to be brought home from camp early because she hates it and thinks she has no friends — leaving her with little to do but to hang around the house for long, idle, sun-drenched days.

We get glimpses of Janet’s friendships and failed relationships, all seen from Lacy’s perspective. Bad boyfriends exit the film with cheeky title cards like “End Wayne.” The eccentricity of the region’s hippie milieu is put to droll use, stressing the strangeness of acupuncturist Janet’s new age circle without resorting to caricature. (Baker’s western Mass. could be a cousin to Kelly Reichardt’s Portland, Oregon.) The outside world is a strange and confounding place — not to mention full of ticks — so Lacy prefers to stay indoors, arranging her toys and dolls into dioramas within a makeshift proscenium, perhaps presaging a career as a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright?

I’m not sure how explicitly autobiographical “Janet Planet” is supposed to be, but a lot of these scenes have the specificity of lived experience. An early, especially Proustian trip to the Hampshire Mall conjures the majesty of indoor fountains and the wonder of Waldenbooks. I’ve never seen a movie get so much mileage out of a JCPenney sign.

As with Baker’s plays, the silences are long and the dialogue oblique. Medford native Nicholson is an ideal fit for the writer’s style, inhabiting the movie’s minimalist aesthetic with unshowy precision. (She’s been a secret weapon of indie filmmakers since 2000’s “Tully” and nobody’s yet caught her “acting.”) The owlish Ziegler is a fascinating discovery, like a baby Carol Kane made up entirely of right angles. The women of “Janet Planet” are so inward and composed, the men can’t help but come off as clumsy and pleading in their presence. The great Will Patton and Elias Koteas show up as suitors attempting to woo Lacy’s mom with varying degrees of success; odd, hairy intruders who are in the picture until they aren’t anymore.

“Janet Planet” can occasionally be a frustrating picture. Baker’s penchant for real-time longueurs doesn’t always translate as well to the screen as it plays onstage, where being boring on purpose carries with it an entirely different electricity. But the movie has a canny, cumulative effect, putting us in Lacy’s shoes as she gets the lay of the land. The last scene is downright thrilling, making deft use of dance to show us a shy, young girl at last beginning to understand the adult world that’s literally spinning and twirling around her. She’s finally ready to join in.

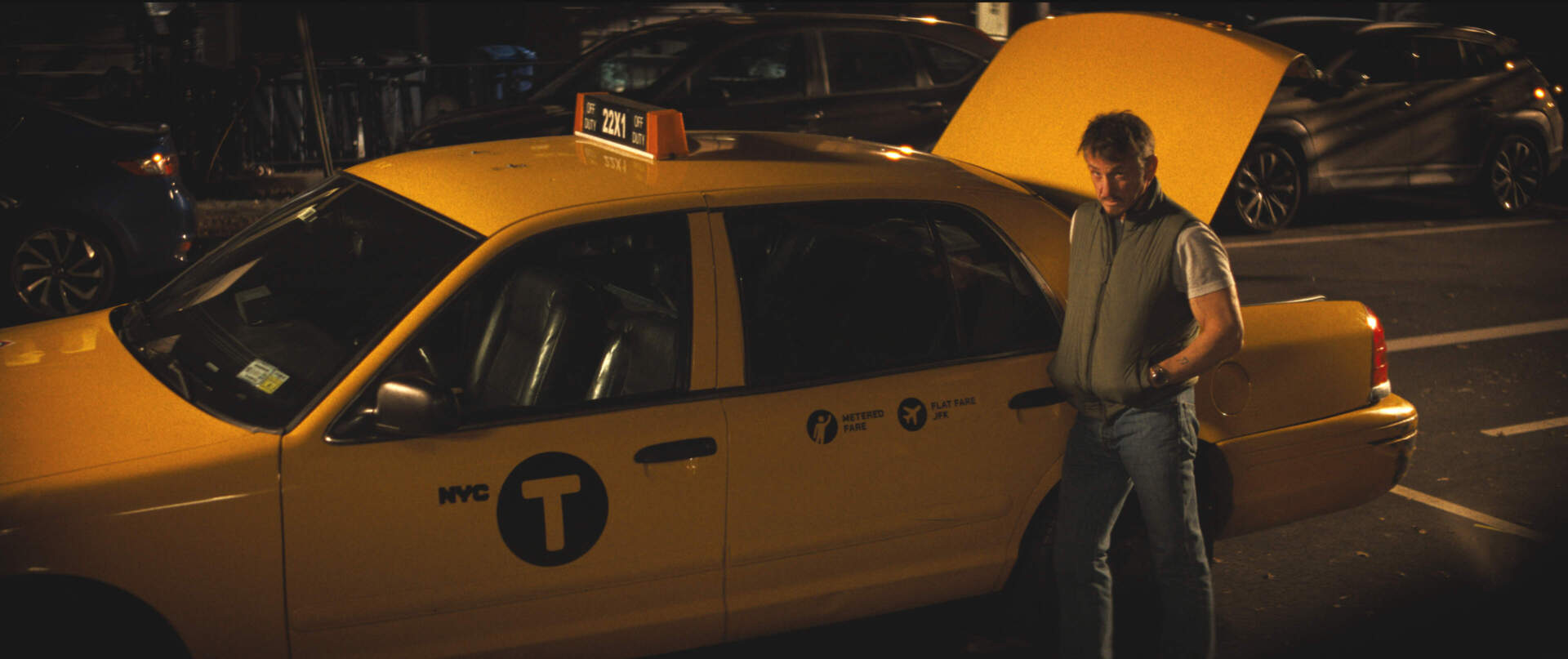

I find that one of the most difficult things to explain to young people these days is just how much Sean Penn meant to us in the 1980s and ‘90s. Penn was such an electrifying presence back then; a surly, chain-smoking, antisocial antidote to the freshly scrubbed Brat Pack, and heir to the Method mantle of De Niro and Pacino. He’s since become such a horrifically obnoxious public figure, Penn’s somehow able to engender ill will while involved in a whole host of heroic, humanitarian causes. Also, the movies he makes now are mostly bad, which is why the abysmally titled “Daddio” is such a delightful surprise. This modest two-hander stars Penn and Dakota Johnson, another gifted performer not particularly well served by her roles as of late. She plays a woman returning to New York City after a trip home to visit her estranged sister in Oklahoma. Penn plays the chatty cabbie who picks her up at the airport.

And that’s it; that’s the story. First-time director Christy Hall adapted the film from her own play, and mercifully doesn’t try to trick it out with any attempts to “open up” or vary the locations. You take two terrific actors sinking their teeth into a meaty script, and you’ll happily watch them do so in a traffic jam. Penn hasn’t been this charming in eons, playing a salty-mouthed know-it-all savvy enough to understand that he’s a caveman relic from another age and perfectly content to have fun with that. He needles Johnson with some provocative, politically incorrect banter and is taken aback to discover she gives as good as she gets. Their affectionate trash talk soon takes a more substantive turn, until eventually these two wind up confessing the kind of secrets you’d only tell a stranger who you know you’ll never see again.

Advertisement

As enjoyable as it is to watch Penn in such relaxed, old-pro mode, I imagine Johnson — who also produced the picture — will be the revelation for most moviegoers. The cabbie describes her as “a woman who can handle herself,” and the actress layers intriguingly tough dimensions beneath her bombshell femininity, suggesting someone who’s also been around the block a few times but is still capable of being hurt. Her character — known only as “Girlie” in Hall’s script — is a mistress to an older, married man with whom she’s made the mistake of falling in love. He’s badgering her with gross texts throughout the ride, and one of the things “Daddio” does so well that I haven’t seen in a movie before is dramatizing how, thanks to our phones, these days we’re all usually in the midst of multiple conversations at once.

What’s so refreshing is that there aren’t any overt lessons being learned here. This ride isn’t going to change either of their lives, no matter how bad the traffic. One conversation couldn’t possibly be enough to get him to stop being such a chauvinist pig, and I don’t think she’s about to straighten out her relationships and live happily ever after. What Hall’s film captures is something far more important and elusive. It’s about how an unexpected human connection — even one as fleeting as a cab ride — can deepen and enrich the way we see the world around us. I really liked this movie a lot.

“Janet Planet” and “Daddio” are now in theaters.