Advertisement

'There Are No Black Faces': The Cautionary Tale Of Arsenal's 1992 Mural

Resume

First, it was baseball in Taiwan and South Korea. Then it was soccer: first Germany's Bundesliga and, now this week, England's Premier League. Sports are starting to come back. And as they come back, leagues around the world are trying to figure out how to make the games look and feel less empty.

The New York Times' Rory Smith recently wrote about how one well-known Premier League team once solved the empty grandstand problem, though this story is a bit of a cautionary tale.

Rory Smith joined us to talk about that.

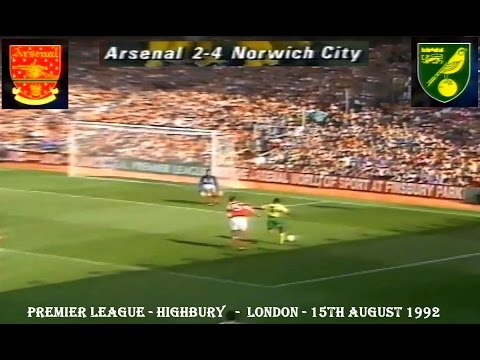

KG: The year was 1992. The team was Arsenal. There was obviously no pandemic forcing fans to stay at home. So, what was the problem?

RS: So in 1989 English football suffered the Hillsborough disaster, which involved the death of 96 Liverpool fans, partly because of a kind of rotting terrace at a stadium in Sheffield. And that led to the Taylor Report, which was a government investigation, which made it clear that English football had to update its stadiums. So every club in England had to do something about their stadiums. And some of them kind of put in seats while they were playing. Some of them knocked down certain stands and rebuilt them.

And Arsenal, which had its old stadium, Highbury, the kind of hard core Arsenal fans gathered on the North Bank of Highbury, which is one of the ends of the stadium. And it needed to be knocked down to be replaced with an all-seater stand. So Arsenal's vice chairman at the time, a man called David Dein, decided that what they would do would be to play the season while the stand was still being built.

He didn't want loads of sort of cement trucks and cranes spoiling the spectacle. They would hide the construction work with a mural. A mural that made it look like there were fans there. And David Dein felt that this was the best way out of the problem.

KG: So David Dein, he enlisted an artist to help him with this solution. So who did he bring in to help out?

RS: He contacted a firm called January, and they handed it to an artist of theirs, a resident artist, by the name of Mike Ibbison, who happened to be an Arsenal fan. And they basically said to him, "Look, we've got this commission for a mural of fans. What does that look like?" And I guess, because that had never been done before, he got to run with the full gamut of his imagination.

KG: All right, so this mural was designed and then painted by hand, and the whole process took, like, a month. And then it was hung in place. And no one during this entire time noticed that there was something wrong with it?

RS: No. This is where it becomes, as you say, a slightly cautionary tale about subconscious bias. So Mike, in his recollection, basically drew a vision of a crowd, a mural basically encompassing the whole width of the pitch on which were painted lots and lots of Arsenal fans celebrating, wearing jerseys, holding scarves aloft. He didn't give anybody an ethnicity. If you actually looked really closely at the mural, they're basically formless human shapes. He wasn't trying to create a kind of cross-section of Arsenal fans. It was just, "Here are some human shapes in Arsenal shirts."

"Kevin Cambell said, 'What can't you see? ... There are no Black faces.' And he was quite right."

Rory Smith

And so, when the mural was mounted on a scaffold in front of the North Bank, it did its job. It hid the scaffolding, it hid the cement trucks, it hid the cranes. Everybody thought, "That looks great. This is exactly what we needed." And, the day before the first game of the season, Arsenal were invited to go through one final training session on the pitch. And two of the team's Black players, Kevin Campbell and Ian Wright, were warming up. And Kevin Campbell, after a few minutes, turned to Ian Wright and said, "Look at the mural." So Ian Wright did. And Kevin Cambell said, "What can't you see?" And Ian Wright stared at the mural for a while and eventually thought, "I have no idea what this man is talking about. Please enlighten me." And Kevin Campbell said, "There are no Black faces." And he was quite right.

And, as Kevin Campbell came off the field that day, David Dein was walking around the side of the pitch. And Kevin Campbell stopped him and said, "There are no Black faces in this mural." And David Dein looked up and, I suppose to his credit, said, "Yes, you're absolutely right. That's unacceptable."

Arsenal at the time was well known, really, for having a much more diverse fan base than most teams. This is still the very early '90s in England when it was only a few years beforehand that soccer really hadn't been a welcoming environment to any people of color. It was not a safe place a lot of the time for anyone of color, or families, or women, or anyone who wasn't, basically, a white male to be. Arsenal, famously, had quite a diverse fan base and was very proud of that fact. And David Dein recognized immediately that it was not acceptable to whitewash that element of the club's identity.

Advertisement

And, that night, the mural was amended. ... Black faces were painted in. And by the time of the first game, the mural contained a much more accurate depiction of Arsenal's traditional fan base than it would have done otherwise.

KG: And then this story kinda enters urban legend territory, because there are all sorts of rumors about what happened next.

RS: That in a way, kind of adds to the story of the mural. There are theories that it was repainted again to include women, which everybody involved denies. There's then a story that it was repainted yet again, because all of the amendments had meant that lots of children weren't with their parents. (Which, I guess, would have annoyed people who believe that parents should look after children, I suppose.)

And then there are the apocryphal tales that some nuns were painted into the mural, a Manchester United fan was painted into the mural. Everybody denies this. Everybody involved says that the mural was amended once to reflect the actual diversity of Arsenal fanbase and never again. But it has kind of obtained this slightly mythical status of this enormous kind of error that Arsenal made.

KG: One of the things I love about this story is that normally you would just be able to go and, say, look at the mural and be like, "How many times does it look like it's been repainted? Who is in it? Are there nuns?" But we can't do that. So what happened to this mural after it came down?

RS: That's an extremely good question. It has effectively disappeared without trace. Mike Ibbison, who I guess owns the intellectual property to the mural, not only doesn't know where the mural itself is, but doesn't know where his original sketch is. So there is of kind of nothing to check it by.

"We are all susceptible to our own unconscious biases."

Rory Smith

There are theories, there are rumors, that the mural was caught up and kind of given to fans as a keepsake — which would be nice and kind of romantic and would vaguely make sense. But, then, not many Arsenal fans at the time regarded it particularly fondly. Partly, I think, because of the controversy that grew up around it, but partly because Arsenal had a really bad season that year. And as all fans know, if there's a scapegoat to be had, you use that scapegoat. So that Arsenal's bad season became the fault of the mural.

So I'm not sure there's anyone who would particularly want to have this sort of cursed mural in their house. But, as things stand, no one I spoke to knows where any of it is, which is extraordinarily given the sheer scale of it. It's a stadium-sized thing, and it has disappeared completely without trace.

KG: Well, clearly, in 2020, organizations are much more aware of the importance of representation than they were in 1992. But still, are there lessons teams should take from this story as they try to make their venues look and feel less empty?

RS: I think there are lessons for all of us. I don't think that Mike Ibbison set out to draw a white crowd. I don't think that David Dein envisaged only having white faces on that mural. I don't think there was any kind of conscious decision that, "We want this mural to be white." I don't think there was a conscious decision to erase Black identity within the mural or to whitewash Arsenal's fan base. But what it proves, I think, is that we are all susceptible to our own unconscious biases.

Both David Dein and Mike Ibbetson sort of felt that that mistake wouldn't happen now. But it happens all of the time. Companies advertise products, and they use exclusively white models. Or they market in a way that speaks to white people, and not to Black people, or to people of color.

We would all like to think that it couldn't happen again. I think the evidence is that it does happen continually. And maybe the lesson to be learned from the North Bank mural is that we just need to be aware, that we need to be careful, we need to be mindful of what society looks like and aware of the way that we think and the shortcomings within that.

Check out Rory Smith's recent New York Times story "The Shirts Were Red. The Fans Were All White."

This segment aired on June 20, 2020.